The Ambiguity of Affirmative Action: Analysis of the Temporary Arrangement Argument

The policy of affirmative action has been suggested as a temporary arrangement, this article will attempt to discern on what basis and why such policies should be ended? First, this article will PROVIDE A brief overview of the policies of Affirmative Action. Second, it will explore the pejorative critiques. Third, it will outline five reasons inherent to the policy that make it ambiguous, arguing that this ambiguity results in self-perpetuation. Therefore, this article will assert that the concept of temporal arrangement is merely a way to placate pejorative critiques of the policy. Finally, this temporal ambiguity is necessary to continue affirmative action – in the liberal democratic context and elsewhere – which, while still problematic, should be adjusted to strategically target the disadvantaged beyond identity-markers given its positive outcomes on societal diversity and integration.

The policy of affirmative action has been suggested as a temporary arrangement, this article will attempt to discern on what basis and why such policies should be ended? First, this article will PROVIDE A brief overview of the policies of Affirmative Action. Second, it will explore the pejorative critiques. Third, it will outline five reasons inherent to the policy that make it ambiguous, arguing that this ambiguity results in self-perpetuation. Therefore, this article will assert that the concept of temporal arrangement is merely a way to placate pejorative critiques of the policy. Finally, this temporal ambiguity is necessary to continue affirmative action – in the liberal democratic context and elsewhere – which, while still problematic, should be adjusted to strategically target the disadvantaged beyond identity-markers given its positive outcomes on societal diversity and integration.

There is no universal definition of affirmative action[1], positive action[2] or positive discrimination[3], however the UN suggests that “Affirmative action is a coherent packet of measures, of a temporary character, aimed specifically at correcting the position of members of a target group in one or more aspects of their social life, in order to obtain effective equality.”[4] There are competing interpretations from the ECHR, ILO, ICCPR but for the purposes of this article, affirmative action can be generally defined as a liberal democratic approach to enhancing a disadvantaged groups’ equality of opportunity within the grasp of the state. At a practical level this policy has two direct outcomes; one can mean that when two equally qualified individuals apply for a position such as higher education[5] the individual belonging to a disadvantaged group is awarded the position; more controversially, it also can prohibit members of a non-designated group from applying for opportunities while less qualified members of a designated group with lower individual merit are awarded the position.

There is no universal definition of affirmative action[1], positive action[2] or positive discrimination[3], however the UN suggests that “Affirmative action is a coherent packet of measures, of a temporary character, aimed specifically at correcting the position of members of a target group in one or more aspects of their social life, in order to obtain effective equality.”[4] There are competing interpretations from the ECHR, ILO, ICCPR but for the purposes of this article, affirmative action can be generally defined as a liberal democratic approach to enhancing a disadvantaged groups’ equality of opportunity within the grasp of the state. At a practical level this policy has two direct outcomes; one can mean that when two equally qualified individuals apply for a position such as higher education[5] the individual belonging to a disadvantaged group is awarded the position; more controversially, it also can prohibit members of a non-designated group from applying for opportunities while less qualified members of a designated group with lower individual merit are awarded the position.

The justifications for implementing an affirmative action policy are compelling. It is compensation against intentional or accidental discrimination and past grievances – such as slavery – perpetrated by the dominant ethnie[6] and/or gender. It is seen as a necessary enhancement of diversity in the public and private sector of a society against the perpetuation of wealth and segregated social networking.[7] It can facilitate symbolic achievement of a minority group individual thus improving their collective standing in the perceptions of the dominant ethnie. It seeks to move to a society of equality of opportunity meaning taking into account the substantive[8] legal disadvantages or differences that formal legal equality does not. It is not just combating discrimination based on inalienable ethnicity or gender but combating legal interpretations of equality that advantage the dominant ethnie (white) and gender (male). Formal equality would allow Sandra Lovelace to be treated equally in relation to other Indian women but not equally to a male Indian under the provisions of the Canada’s Indian Act[9] which restricts the definition of Aboriginal membership by gender. Substantive equality and affirmative action are congruent legal concepts.

The justifications for implementing an affirmative action policy are compelling. It is compensation against intentional or accidental discrimination and past grievances – such as slavery – perpetrated by the dominant ethnie[6] and/or gender. It is seen as a necessary enhancement of diversity in the public and private sector of a society against the perpetuation of wealth and segregated social networking.[7] It can facilitate symbolic achievement of a minority group individual thus improving their collective standing in the perceptions of the dominant ethnie. It seeks to move to a society of equality of opportunity meaning taking into account the substantive[8] legal disadvantages or differences that formal legal equality does not. It is not just combating discrimination based on inalienable ethnicity or gender but combating legal interpretations of equality that advantage the dominant ethnie (white) and gender (male). Formal equality would allow Sandra Lovelace to be treated equally in relation to other Indian women but not equally to a male Indian under the provisions of the Canada’s Indian Act[9] which restricts the definition of Aboriginal membership by gender. Substantive equality and affirmative action are congruent legal concepts.

The pejorative critique of affirmative action almost overwhelms the justifications. While race and economic class converge at the bottom, the policy is inexact; it often advantages the socio-economically advantaged while under privileging the less skilled in a discriminated group while simultaneously disadvantaging the poor in the dominant ethnie who then mobilize through democratic means. Their consternation is about fairness and the individual versus group conceptions of equality. Should affluent African American children be beneficiaries of the policy? In addition, affirmative action fights racism by categorizing people using ethnicity: the very object of discrimination. Who decides who you are? Another common complaint is that weaker admitted candidates may do poorly through such programs and have a psychological backlash as demonstrated by the Madeline Heilman Study.[10] In addition, the most damaging critique is – according a prominent beneficiary of affirmative action; Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas – these policies perpetuate inequality, disrespect and that the normative goal of the US “constitution [to be] color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerated classes of citizenship.”[11]

The pejorative critique of affirmative action almost overwhelms the justifications. While race and economic class converge at the bottom, the policy is inexact; it often advantages the socio-economically advantaged while under privileging the less skilled in a discriminated group while simultaneously disadvantaging the poor in the dominant ethnie who then mobilize through democratic means. Their consternation is about fairness and the individual versus group conceptions of equality. Should affluent African American children be beneficiaries of the policy? In addition, affirmative action fights racism by categorizing people using ethnicity: the very object of discrimination. Who decides who you are? Another common complaint is that weaker admitted candidates may do poorly through such programs and have a psychological backlash as demonstrated by the Madeline Heilman Study.[10] In addition, the most damaging critique is – according a prominent beneficiary of affirmative action; Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas – these policies perpetuate inequality, disrespect and that the normative goal of the US “constitution [to be] color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerated classes of citizenship.”[11]

Ambiguity of Affirmative Action

This article accepts the positive outcomes of affirmative action policy as outweighing the pejorative critiques with some adjustments, and will now focus specifically on the question of affirmative action as a temporary arrangement, arguing that a) ambiguity results in perpetuation of the policy and b) that a completion date for these policies is merely a way to placate pejorative critiques of the policy.

The Morawa article highlights the details of affirmative action as a temporary arrangement, first introduced in November of 1963. Quoting the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, affirmative action should protect disadvantaged groups “…however…such measures do not, as a consequence, lead to the maintenance of separate rights for different racial groups and that they shall not be continued after the objectives for which they were taken have been achieved.”[12] If this were true then why is there no proposed concrete mechanism or rubric specifying measurable completion and dismantling? The reality of most affirmative action policies is quite divergent from this assumption of temporary arrangement. The spectrum of continued affirmative action moves from immediate nullification to the disingenuous temporary status to permanence. Affirmative action has been given an end point but only forcibly through the will of the majority as was the case of Proposition 209 in California and Michigan Proposal 2006-2[13] and judicial adjustments to some policies. Never have affirmative action policies been dismantled on the basis of complete success in their objectives: the reasons are numerous but all fall under the idea of temporal ambiguity.

The Morawa article highlights the details of affirmative action as a temporary arrangement, first introduced in November of 1963. Quoting the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, affirmative action should protect disadvantaged groups “…however…such measures do not, as a consequence, lead to the maintenance of separate rights for different racial groups and that they shall not be continued after the objectives for which they were taken have been achieved.”[12] If this were true then why is there no proposed concrete mechanism or rubric specifying measurable completion and dismantling? The reality of most affirmative action policies is quite divergent from this assumption of temporary arrangement. The spectrum of continued affirmative action moves from immediate nullification to the disingenuous temporary status to permanence. Affirmative action has been given an end point but only forcibly through the will of the majority as was the case of Proposition 209 in California and Michigan Proposal 2006-2[13] and judicial adjustments to some policies. Never have affirmative action policies been dismantled on the basis of complete success in their objectives: the reasons are numerous but all fall under the idea of temporal ambiguity.

There are at least five reasons why affirmative action has an ambiguous end point that cannot be specified. Below are five specific ways in which affirmative action policies remain ambiguous on the matter of termination:

There are at least five reasons why affirmative action has an ambiguous end point that cannot be specified. Below are five specific ways in which affirmative action policies remain ambiguous on the matter of termination:

First, the most logically deduced answer to when affirmative action should cease is at the point where the number of employment or academic positions are proportionate to the groups percentage of the population. That is, the disadvantaged group demographic size mirrors and has reached equilibrium with the demographic representation within the public and private spheres of society. There are several problems here but most obvious is that once the policy has reached this watermark and is therefore effectively terminated, the subsequent absence of this policy would lead to decline in proportionality since establishing this proportionality required the express support of the state.[14] Therefore, affirmative action is a self-perpetuating policy that cannot be suddenly ended because it is an artificial imposition that cannot continue to work without the state. Some kind of gradual approach might remedy this first issue but there are other reasons for ambiguity.

The second problem is that, according to Morawa, affirmative action should be curbed based on whether the objective equality has been met. Objective equality is when “no reasonable and objective criteria exist that would justify a differentiation in treatment.”[15] This then leads to questions of what it means to be objective and whether the equality is reasonable. Interpretation of these two words can have affirmative action nullified tomorrow or never depending on the political leanings of the policy-markers.

The second problem is that, according to Morawa, affirmative action should be curbed based on whether the objective equality has been met. Objective equality is when “no reasonable and objective criteria exist that would justify a differentiation in treatment.”[15] This then leads to questions of what it means to be objective and whether the equality is reasonable. Interpretation of these two words can have affirmative action nullified tomorrow or never depending on the political leanings of the policy-markers.

The third problem is that affirmative action is anticipated to produce side-effects requiring further policy measures to deal with new forms of discrimination created in the wake of the initial policy. Morawa argues that “…Even action taken with the legitimate intent to remedy existing inequality adversely affecting one particular group may have an ‘unjustifiable disparate impact’ upon, or ‘disproportionately affect’ the rights of another distinguishable group.”[16] If there is continued anticipation of new distinguishable groups then the policies are effectively permanent only changing the identities of the beneficiaries.

The fourth problem would be that, according to the variety of cross-sectional cases highlighted by Modood, simply knowing when equality has been achieved is difficult to empirical quantify. Not all companies in the private and even the public sphere record detailed recruitment statistic to verify if the policy actually works. The constantly changing demographics of new immigrants also makes empirical measurements of any kind dubious at best. Therefore, ascertaining whether the policy is improving the situation of disadvantaged groups and the exact extent of that improvement is not being empirical measured. It was not until the Clinton’s 1995 Affirmative Action Review, that there were calls for “continual process to review the effectiveness and fairness of affirmative action programmes.”[17] In light of this, if there is no rigorous assessment there will be no means of ascertain its end point.

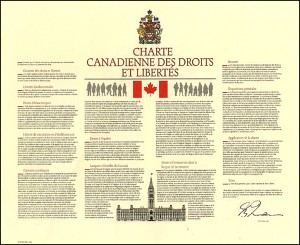

The fifth problem that has led to ambiguity is that politicians and legal scholars have entrenched affirmative action policies into their constitutions. This is particularly apparent in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms which gives provisions for Affirmative Action under Section 15 subsection 2.[18] The idea of a permanence in the policy conflicts with the goal of the policy as a longterm means to eventually do away to eventually eliminate prejudice. It suggests that since there will always be differences, there must always be discrimination and anti-discrimination. Implicit in the policy is that there is no end but continued permanence to an unspecified point. This article suggests this high degree of ambiguity regarding such policies serves to perpetuate them: it is a structural reality with no particular agency other than the original policy creators.

The fifth problem that has led to ambiguity is that politicians and legal scholars have entrenched affirmative action policies into their constitutions. This is particularly apparent in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms which gives provisions for Affirmative Action under Section 15 subsection 2.[18] The idea of a permanence in the policy conflicts with the goal of the policy as a longterm means to eventually do away to eventually eliminate prejudice. It suggests that since there will always be differences, there must always be discrimination and anti-discrimination. Implicit in the policy is that there is no end but continued permanence to an unspecified point. This article suggests this high degree of ambiguity regarding such policies serves to perpetuate them: it is a structural reality with no particular agency other than the original policy creators.

The question is why is it not clear when the policy should (if ever) be nullified: immediately, in 25 years or never? As is argued above, there is no limit for the foreseeable future unless it is forcibly nullified. Justice Sandra O’Connor’s claim, during the 2003 Grutter v Bollinger case, that the “[US Supreme] Court expects that twenty fiver years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today”[19] is so plainly arbitrary that it borders on rhetorical obfuscation. That is why, this article has argued that temporary arrangement claims are primarily a means of placating those who are not completely convinced of the virtues of affirmative action with the idea that it will not exist forever. A completion date for these policies is merely a means for liberals to argue for its continued support since their belief in the sacred value of individual rights is contradicted by support for disadvantaged rights. Unless these policies are forcibly removed – which is not desirable – the effect of continuing the myth of a temporary status placates critiques of the policy since it is purposively not permanent while effectively entrenching an unspecified permanence to such policies.

The question is why is it not clear when the policy should (if ever) be nullified: immediately, in 25 years or never? As is argued above, there is no limit for the foreseeable future unless it is forcibly nullified. Justice Sandra O’Connor’s claim, during the 2003 Grutter v Bollinger case, that the “[US Supreme] Court expects that twenty fiver years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today”[19] is so plainly arbitrary that it borders on rhetorical obfuscation. That is why, this article has argued that temporary arrangement claims are primarily a means of placating those who are not completely convinced of the virtues of affirmative action with the idea that it will not exist forever. A completion date for these policies is merely a means for liberals to argue for its continued support since their belief in the sacred value of individual rights is contradicted by support for disadvantaged rights. Unless these policies are forcibly removed – which is not desirable – the effect of continuing the myth of a temporary status placates critiques of the policy since it is purposively not permanent while effectively entrenching an unspecified permanence to such policies.

The ambiguity of affirmative action ultimately does not resolve the complaints, shortcomings and the contravention of individual merits rights. The negative side-effects almost derail the positive outcomes as was outlined above but a temporary arrangement is not going to resolve the underline pejorative critiques. There are many previous groups who have risen from collective poverty in America to be successful integration without affirmative action, particularly the Irish case.[20] Meanwhile, there are visible minorities who continue to struggle with policies that entrench their legal differentiation from society. The numerous treaties signed between the Crown and Aboriginal peoples in Canada is a permanent form of affirmative action which has limited or mixed results far to complicated to be addressed within this short article.

In conclusion, this article will briefly focus on what is to done about the ambiguity of affirmative action policies. Affirmative action needs to change who it targets not be nullified. If there is continued anticipation of new distinguishable groups then the policies are effectively permanent only changing the identities of the beneficiaries. Having said that, affirmative action has no limit as a permanent policy that contravenes individual merit with the goal of raising groups out of social inequality. There will always be somebody at the bottom and affirmative action will always have a role to play if the polity’s majority is willing to accept it. The policy of affirmative action has been suggested as a temporary arrangement, this article attempted to discern on what basis should such policies be ended by examining the policy of affirmative action with particular emphasis on the pejorative critiques which a temporary arrangement partly offsets but does not resolve. It outlined five reasons inherent to the policy that make it ambiguous and effectively permanent. Concluding that given this ambiguity of affirmative action policies, it should remain as long as the majority groups has tacitly accepted it and recognize that it is a permanent fixture that continues into future generations.

In conclusion, this article will briefly focus on what is to done about the ambiguity of affirmative action policies. Affirmative action needs to change who it targets not be nullified. If there is continued anticipation of new distinguishable groups then the policies are effectively permanent only changing the identities of the beneficiaries. Having said that, affirmative action has no limit as a permanent policy that contravenes individual merit with the goal of raising groups out of social inequality. There will always be somebody at the bottom and affirmative action will always have a role to play if the polity’s majority is willing to accept it. The policy of affirmative action has been suggested as a temporary arrangement, this article attempted to discern on what basis should such policies be ended by examining the policy of affirmative action with particular emphasis on the pejorative critiques which a temporary arrangement partly offsets but does not resolve. It outlined five reasons inherent to the policy that make it ambiguous and effectively permanent. Concluding that given this ambiguity of affirmative action policies, it should remain as long as the majority groups has tacitly accepted it and recognize that it is a permanent fixture that continues into future generations.

Work Cited

-

A. H. E. Morawa, “The Concept of Non-Discrimination: An Introductory Comment”, Journal of Ethnic and Minority Issues in Europe, 3, 2002

-

California Proposition 209: accessed 18.03.09: http://vote96.sos.ca.gov/BP/209text.html

-

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom: accessed 18.03.09: http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/charter/

-

E. Kaufmann, ‘National Formation, Ethnic Reformation: the Social Sources of the American Nation’, Geopolitics, 7 (2), 98-120.

-

Grutter v Bollinger 2003: accessed 18.03.09 http://www.enfacto.com/case/U.S./539/306/

-

Heilman, ME (2004). “Penalties for success: Reactions to women who succeed at male gender-typed tasks”. Journal of applied psychology (0021-9010), 89 (3), p. 416.

-

McGoldrick, Dominic. Canadian Indians, Cultural Rights and the Human Rights Committee. The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 40, No. 3 (Jul., 1991), pp. 658-669.

-

Professor Jackson-Preece: “Irish Rise in America.” EU458: Seminar 15.03.09

-

T. Modood et. al, Developing Positive Action Policies: Learning from the Experiences of Europe and North America, 2006

-

United Nations, Concept and Practice of Affirmative Action, 2002

-

[1] Predominant term used in New World high immigrant countries such as Canada, the US and Australia

-

[2] Predominant term used in the EU and the United Kingdom in order to circumvent the pejorative connotations associated with the backlash against affirmative action in the new world context.

-

[3] Predominant term used to emphasize that negative discrimination against disadvantage groups is ubiquitous or alternatively to emphasize the policy is ‘unjust’ towards the dominant ethnie.

-

[4] United Nations, Concept and Practice of Affirmative Action, 2002

-

[5] An essential means of furthering equality of opportunity.

-

[6] Coined by Anthony Smith by used in the Introduction of Kaufmann: E. Kaufmann, ‘National Formation, Ethnic Reformation: the Social Sources of the American Nation’, Geopolitics, 7 (2), 98-120.

-

[7] As in low levels of integration because of limited opportunities to interethnic interaction within the society.

-

[8] Substantive equality: taking into account disadvantages.

-

[9] McGoldrick, Dominic. Canadian Indians, Cultural Rights and the Human Rights Committee. The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 40, No. 3 (Jul., 1991), pp. 667.

-

[10] Heilman, ME (2004). “Penalties for success: Reactions to women who succeed at male gender-typed tasks”. Journal of applied psychology (0021-9010), 89 (3), p. 416.

-

[11] Grutter v Bollinger 2003: accessed 18.03.09: http://www.enfacto.com/case/U.S./539/306/

-

[12] General Assembly Resolution 2106 (XX) of 21 December 1965, Article 1 ( 4). A. H. E. Morawa, “The Concept of Non-Discrimination: An Introductory Comment”, Journal of Ethnic and Minority Issues in Europe, 3, 2002, p. 9.

-

[13] Text of California Proposition 2009: http://vote96.sos.ca.gov/BP/209text.htm

-

[14] In addition, the point at which disadvantaged groups are over represented would lead to a backlash.

-

[15] Morowa, p. 11.

-

[16] Ibid, p. 10.

-

[17] Modood, p. 77.

-

[18] Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom: accessed 18.03.09: http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/charter/

-

[19] Grutter v Bollinger 2003: accessed 18.03.09: http://www.enfacto.com/case/U.S./539/306/

-

[20] Professor Jackson-Preece: “Irish Rise in America.” EU458: Seminar 15.03.09