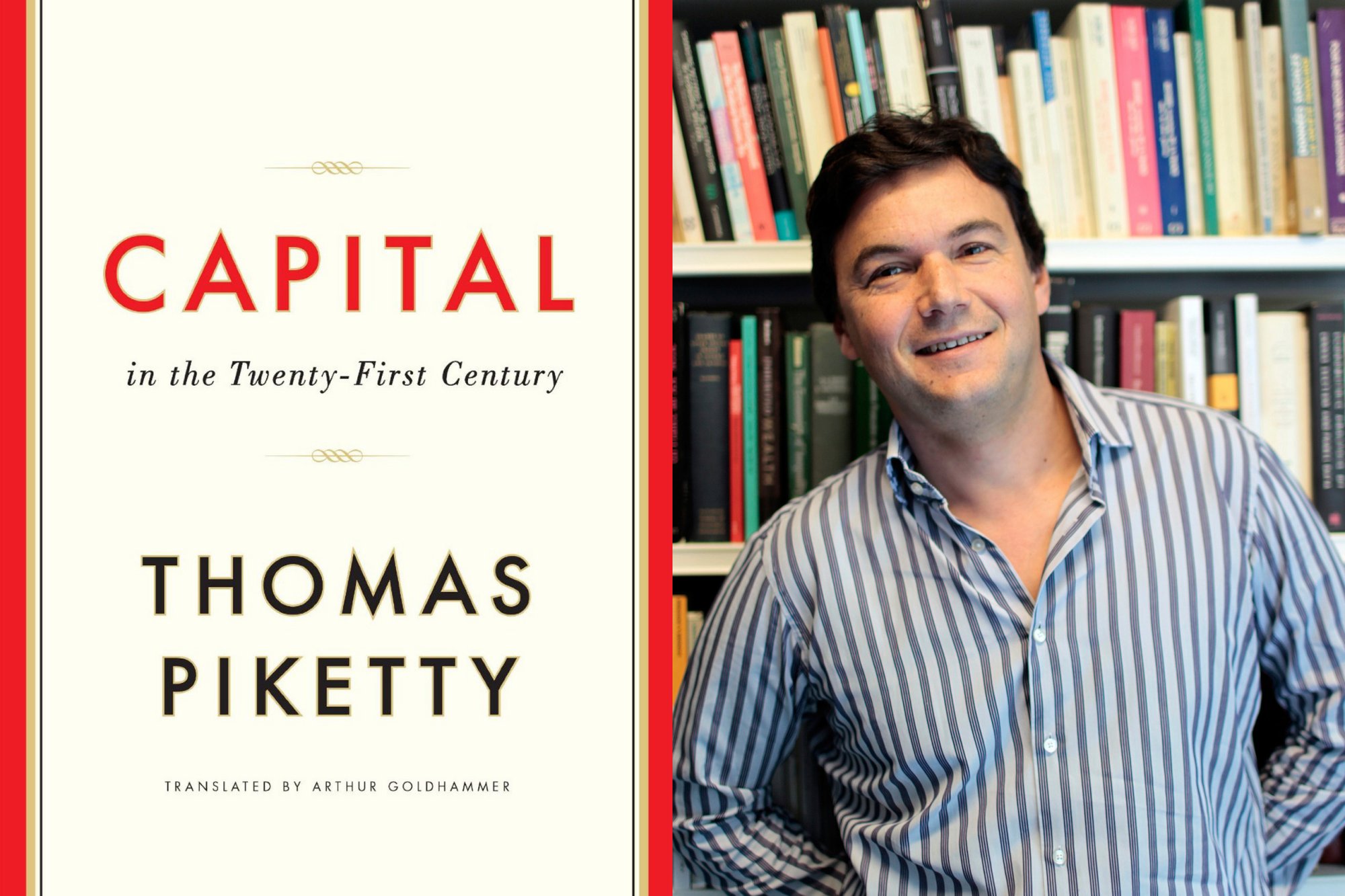

Slides from Capital in the 21st Century, Thomas Piketty

Piketty’s Thesis: Thomas Piketty’s thesis is that the rate of capital returns is greater than the rate of economic growth in developed countries. The message is clear “forget about income/salary inequality, take a look at wealth inequality!” Wealth is getting collected and retained at a faster rate than economic growth is occurring in the overall economy. This assertion is a much more sophisticated argument than the classic “the rich are getting richer.” Private wealth is increasingly concentrating in the hands of ‘the few’ which is troubling since it’s doing so at a faster rate than the rate of new wealth creation. It’s also troubling (if it’s true) that ‘the few’ are just lucky & riding compound interest into a promising future instead of creating true value through their own productivity. This trend has been tracked over the last 250 years and with increasing accuracy since developed countries have implemented income tax. Piketty’s challenge is to address the issue that wealth concentration will grow relative to economic growth in the future without any significant policy changes.

Therein Lays the Controversy: Piketty’s solution is to create a progressive global wealth tax (i.e. a tax that targets all accumulated equity rather than in the income tax and cash). His argument pushed him into global super-stardom in 2014. From The Economist to the Wall Street Journal, Piketty’s data based argument was an important turning point in thinking about taxation policy and wealth distribution.

Editorial Input: Of course, everyone is getting richer: just ask your great great grandparents if they ever skyped with their parents 10 km away, instantly for <$0.01 per minute. Your great grand parents lived on average 25 years fewer than your parents etc etc. Even those below the poverty line today are more wealthy than some of middle class from the 20th century (Um: kinda, depends how you measure wealth). As a species, we are rich relative to our ancestors. And of course, remember that money is a PROXY for VALUE, it doesn’t track a bunch of valuable things like, you know, love and happiness for example. What’s novel about Piketty is he’s saying that wealth (the measurable part) is growing faster than that economic benefits (the measurable part) of new technology, productivity etc. What to do about it requires more thought, multi-variate testing and anticipated the unintended consequences of public policy.

Capital in the 21st Century / Le capital au 21e siècle

The book is in four parts;

- Part 1: Income and Capital

- Part 2: The dynamics of the capital/income ratio

- Part 3: The structure of inequalities

- Part 4: Regulating capital in the 21st century

Income and Capital: The Database

The World top incomes database: Piketty has collected data about income tax because it is available since it’s creation; starting in 1913, the US brought in Income Tax (hence the thought that world war was the motivator is not correct); Canada in 1917, UK in 1915, France 1915. Taxation is excellent for gathering information about citizens in a positive sense, to better empower them and to use that revenue to improve the infrastructure of society; AND to allow citizens to understand how money is shaping their life. It focused people to consider their finances. Income tax also is the basis of Piketty’s data set!!

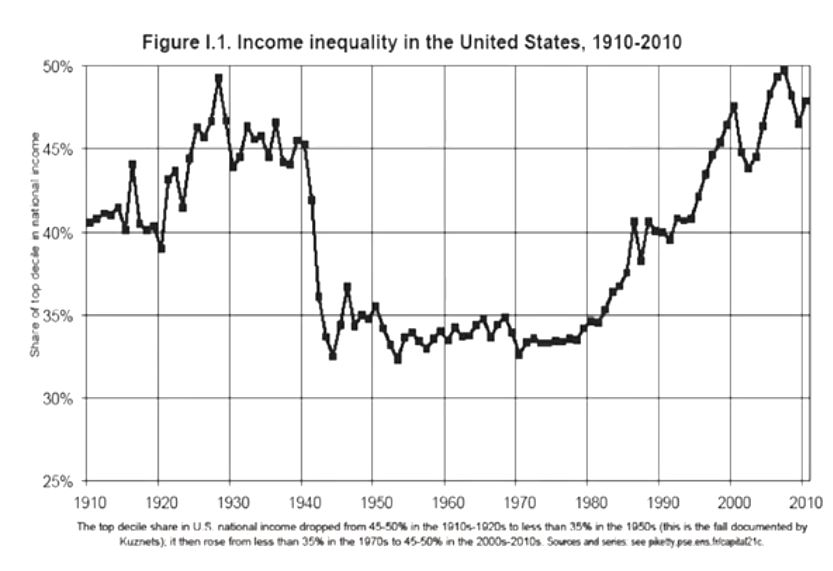

Income Going to the Top 10% (what this graph below shows)

The theory that Income Inequality should decline over time has been proven false in the US. In the past 30 years, the share going to the top has moved to almost 50% of all income. Remember income is all cashflows of an individual. There is a trend towards 50% of the income going to the top 10% today in 2014. So the problem is that the CEOs are getting paid really well but we don’t see extra benefits of their effort in the business; or at least it is difficult to measure. It is difficult to understand how a top manager is able to generate a $10 million income both for and against productivity gains from that individual. It doesn’t mean that CEO isn’t worth every penny and more, it’s just we can’t measure that value well…..

The key for Piketty is that income is, in fact, over-rated. He believes that income inequality is not as interesting or important as is wealth inequality.

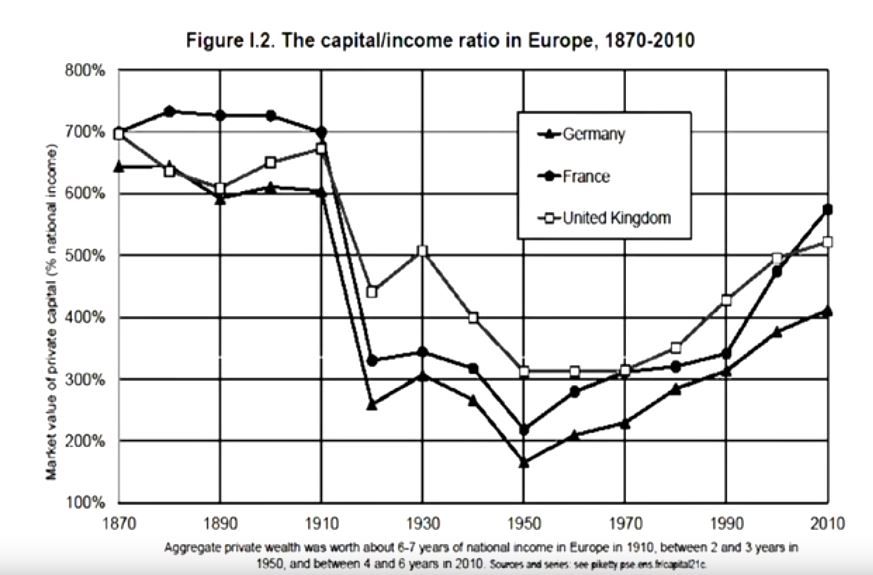

Wealth distribution is more important long-run. The total value of capital and real-estate assets has increased since in the 1960s as you can see below. The inequality in property is very serious. This doesn’t necessarily have to lead to an inequality as a whole. But this graph does represent job income inequality. It dropped as income tax was applied and is creeping back up.

Three Central Points of Capital in the 21st Century:

Three Central Points of Capital in the 21st Century:

- The return of a patrimonial (or wealth-based) society in the Old World (Europe, Japan): Wealth-income ratios seem to be returning to very high levels in low growth countries. Intuition is that a slow-growth society, wealth accumulated in the past can naturally become very important in the future. In the very long run, this can be relevant for the entire world. Population growth in Europe and Japan is low.

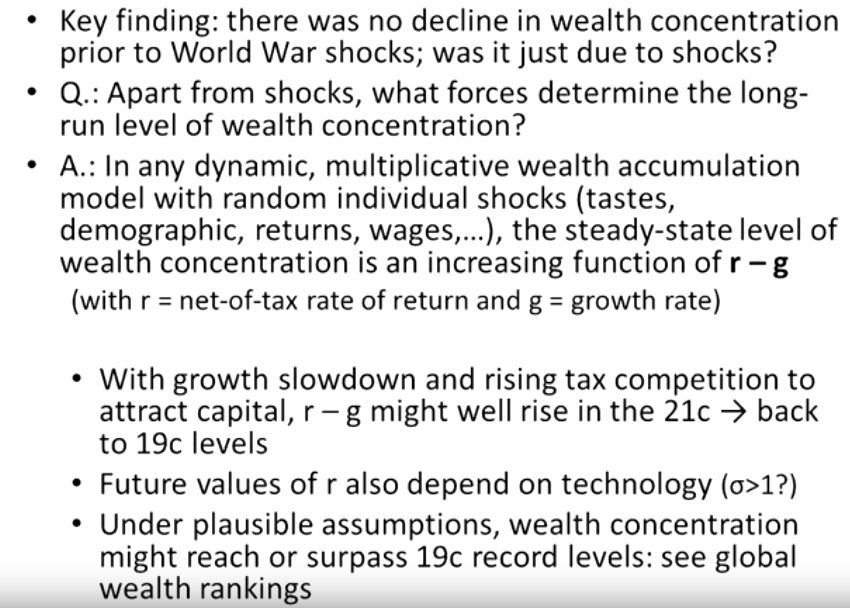

- The future of wealth concentration: with high r-g during the 21st century (r= net-of-tax rate of return, g=growth rate), then wealth inequality might reach or surpass 19th century oligarchic levels; conversely, suitable institutions can allow to democratize wealth. Wealth inequality tends to concentrate better and that we should have more transparency and have more diffusion of wealth.

- Inequality in America: is the New World developing a new inequality model that is based upon extreme labour income inequality more than upon wealth inequality? Is it more merit-based, or can it become the worst of all worlds?

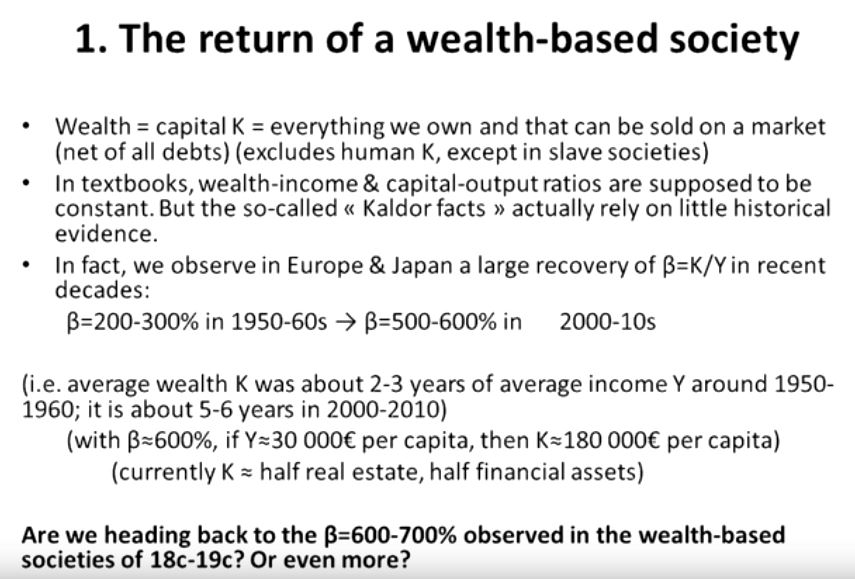

Point 1: The return of a wealth-based society

The ratio of wealth and capital concentration was supposed to a constant, at least that’s what economics textbooks advocate. However in the data, it is not a constant.

The ratio of wealth and capital concentration was supposed to a constant, at least that’s what economics textbooks advocate. However in the data, it is not a constant.

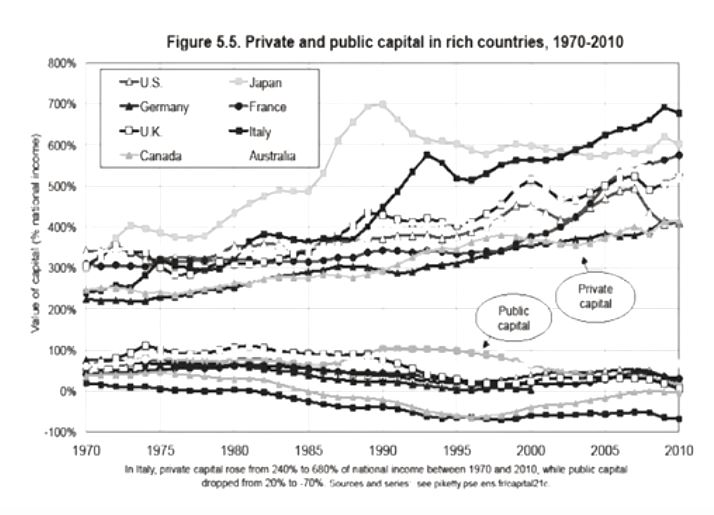

The Beta of private capital. Beta being the level of inequality. Here we can see that over time the level of private capital has grown over time in rich countries from 1970 to 2010. The database is a combination of data which includes real-estate prices and is a bit messy.

Public Debt versus Private Wealth

The rise of wealth in Europe on the private side has grown, but look at the public capital. Many doom sayers are abound stating that public debt is a fast approach train wreck. For example, the balance sheet of Italy would show that they have more debt than they have equity. The rise of public debt is significant as an issue in public discourse. However, this concern about public debt to GDP has to be squared against the private wealth that is left by the babyboomer generation etc. In reality, we own our lives as private citizens. The private wealth of Europeans and North Americans towers over the public debt accumulated by our respective governments. So…….

Imagine a market with 100 people in it. If we think about capital as a pile of apples, it might be illustrative. As individuals we have stock piles of apples. The top 10 each have 15 apples (7 apples are hiding in their trousers), the next 45 have 5 apples and the other 55 people have 1 apple. The issue is that over time, top 10 are getting more apples per year at a faster rate than the 45 people with 5 apples and the other folks with having 1 apple each, and getting a sliver more per year. Wealth is concentrating privately and the government isn’t able to do much about that with out new ways to track wealth. In the long run, if you have a lower growth rate, the total stock of wealth accumulated in the past can naturally be very important giving the top 10 the ability to advance their progeny in ways that the 45 middle class and 55 lower class folks can’t.

Piketty says the following:

Piketty says the following:

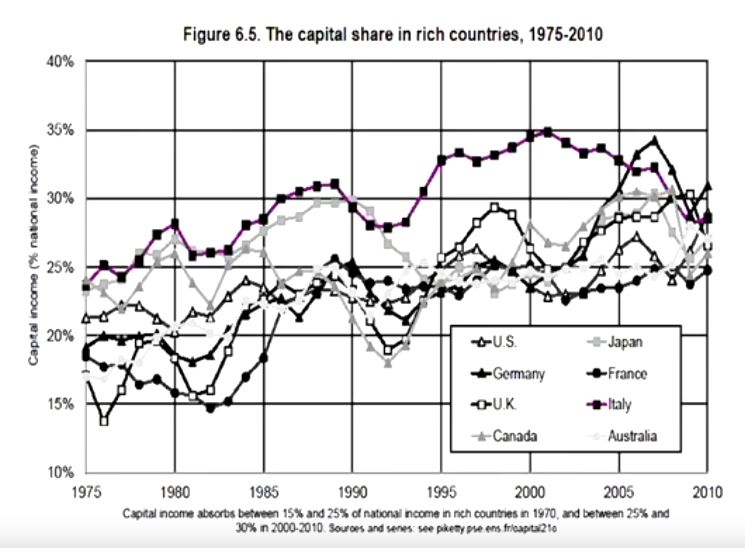

- “Will the rise of capital income – ratio Beta also lead to a rise of the capital share alpha in national income?

- If the capital stock equals Beta = 6 years of income and the average return to capital is equal to r = 5% per yea, then the share of capital income (rent, dividends, interest, profits, etc) in the national income equality alpha = r x Beta = 30%

- Technically, whether a rise in Beta also leads to a rise in capital share alpha = r Beta depends on the elasticity of substitution <a) between capital K and labour L in the production function Y = F(K,L)

- Intuition: <a) measures the extent to which workers can be replaced by machines (e.g. Amazon’s robots)

- Standard assumption: Cobb-Douglas production function (<a)= 1) = as the stock Beta goes Up, the return r goes down exactly in the same proportions, so that alpha = r x Beta remains unchanged, like by magic = a stable world where the capital = labour split is entirely set by technology

- But if alpha > 1, then the return to capital r goes down falls less than the volume of capital Beta goes up, so that the product alpha = r x Beta goes up.

- Exactly what happening since the 1970s-80s; both the ration Beta and the capital share alpha have increased.”

Point 2: The future of wealth concentration

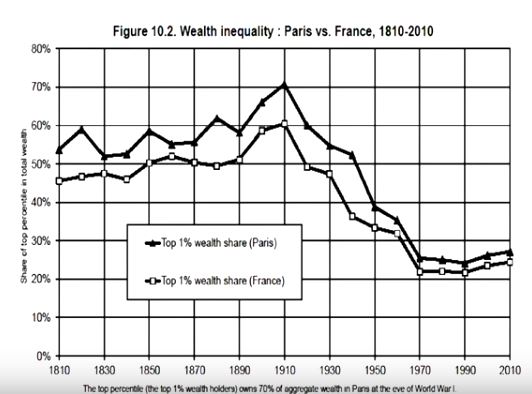

In practice, we have extreme wealth concentration occurring. The direction of national wealth is declining. There was no decline in wealth concentration With income tax, the progressive taxation in France, land was only 5% of the wealth in the 1910s. So what are the forces that explain the wealth concentration?

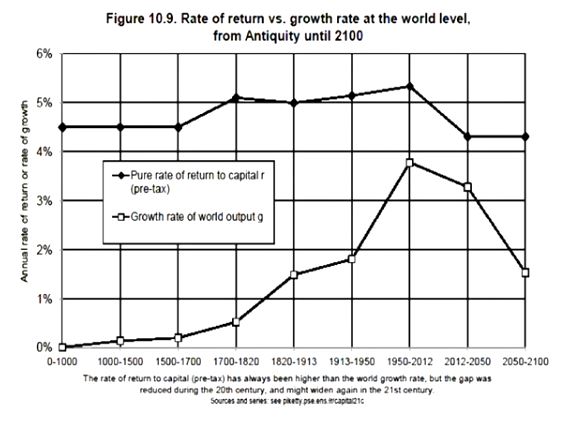

r being bigger than g means that wealth will get amplified over time without intervention.

r and g are moving further. r is larger than g. The growth rate is slow than the rate of return. The industrial revolution increased the growth rate but the rate of return increased as well. So that suggests that inequality has gone down in the 20th century but it’s growing again. The gap between r and g did not change that much before World War 1.

We should be concerned about the concentration of wealth over time! – Piketty

Solutions: Piketty’s Want Equal Access to Skills

You want the most number of people getting access to the information and skills they need to succeed and thrive. It’s the diffusion of equality. The university system, practical education systems that need to improved. You need to reconcile efficiency with access to universities. Inequality to a point can be good for growth and innovation but if inequality gets too extreme it is not good for growth. Inequality before World War I was not helpful according to Professor Piketty. Certainly levels of inequality are just and good, but at a certain point that inequality is counter-productive. Europe had a higher level of inequality Pre-World War 1 than the US.

Solutions: Understanding the Mathematics of Equality

Piketty doesn’t really like Genie Co-Efficient. However, looking at the numbers is more powerful. He believes that thinking about wealth around percentages is better. And by the way, Globalization is a positive sum game, Piketty.

Theoretical Deduction is an Insufficient Basis for Policy Development

Piketty started by collecting data. He wasn’t starting with a hypothesis specifically. He wanted to take his theories of inequality and explore if they were valid based on data collected from >30 countries. Data is better than ideological frameworks.

Transparency and Sanctions

You cannot ask politely for banks to provide more transparency if their clients are benefiting from opacity. Opacity facilitates wealth protection. Steeply progressive tax systems didn’t seem possible until governments brought in the income tax in the 1910s. So Piketty is suggesting a wealth tax is gonna happen, expect it. Sometimes the governments do not have a plan for how to use the funds but with a wealth tax perhaps paying down the government’s public debts is a possible area to fix, thereby lowering interest payments on the declining public debt and liberating that wealth to energize government funding…or something. More research required.

It’s All About the Wealth Tax