Introduction to Futures trading

All right, so I’m really excited about this. This is my Futures Trading tutorials based on my bond trading math tutorials and utilizing Excel and other learning methods. These are powerful ways to learn, and I think you’ll get a lot out of this. We’ll start from simplistic, take it up, ratchet it up incrementally until you’re going to be really well able to understand Futures Trading so let’s get going.

What are Futures?

So, what is a future? Let’s start with that. The textbook definitions are a good waypoint for us, but I do find that academics who are really specialists in the field jump too quickly into technical jargon and detail. And I’m about to basically do that as well, but I want this to be, as I say, like a waypoint or an anchor for us. So that when we go from simple and approachable, following this, you’ll start to build up the knowledge. But it’s good to just know what you don’t know.

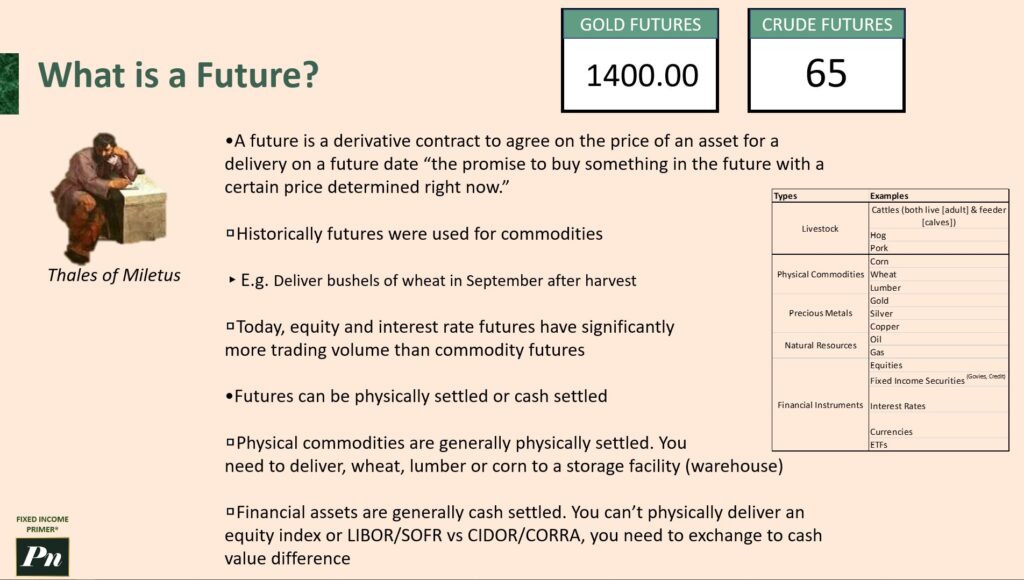

So when you turn on your cable news, you might see a ticker tape at the bottom of the screen, and you’ll have some information flowing. Sometimes it’s the e-mini Dow Futures contract or the e-mini NASDAQ futures contract. And you might see something called the gold futures or crude oil futures, and there are prices displayed there. What’s interesting, you’ll note on the day that you’re watching this cable news, is that maybe gold is actually trading at 1350, and maybe the price of a barrel of oil is actually 55 bucks or 60 bucks. So what’s going on here? What are these Futures really telling you? Well, they’re not quite magic numbers. They’re basically a collection of Futures contracts which suggest a future price for the underlying asset. Here, in this case, gold and crude oil. And that’s really helpful for people to understand where they think the price will be in the future.

So, getting back to it, just really understanding. Like, let’s say this is, uh, like I said, 60 bucks and at 65. So, the price of crude oil is going up in the future and in what time frame? Sometimes it’s the September contract, so it’s in the future. Let’s say it’s in July, September contract, so it’s in the future. So fundamentally, it’s about predicting the future and then getting a reward in exchange for correctly guessing with as much information as you can where the prices will be. And the process of doing that actually creates a fundamentally useful market, a price discovery market. And this concept of price discovery is really powerful because it helps people all around the world decide what is the value of the thing they are trying to price.

When we look at a classic definition, the future is a derivative contract to agree on the price of an asset for delivery on a future date. It’s the prompts to buy something in the future with a certain price-determined rate. Now, that’s a word salad mouthful right there. Like, what is a derivatives contract? Well, if you think about cover bands, so a rock band like the Beatles has many bands that will play covers of Beatles songs. But the covers are actually derivative of the original Beatles because they created the original song, for example, right? I was going to go so far as to say that Oasis is a cover band for the Beatles, but that’s going maybe a bit too far. The truth is that derivative really means it’s not the original or the underlying. So the point is the original is the real deal, and the derivative is the slightly removed from said real deal version of that real deal.

In financial terms, we think of derivatives as representatives of the underlying asset. In this case, it’s gold, crude oil, and we’ll show some other examples. So its value is derived from the original asset, actual gold, but it isn’t actual gold. It’s the future value of gold but spotted today. And what I mean by spotted means the now price or the current price. When people say the spot price, they really just mean the now price. So this is, again, the promise to buy something in the future with a certain price determined now. I commit to giving you at a future date this specific amount of cash for this gold.

Historically, Futures were used for commodities, and I’m going to talk about someone way back, historical person Thales. I think his name is Thales of Miletus. I checked the pronunciation of this multiple times. This is really one of the first originators of the concept of Futures contracts, and we’ll get into it, really kind of the fun story. So, what are the classic Futures contracts about? Well, there’s the delivery of bushels of wheat, for example, in September after harvest in the spring. You don’t know how the season is going to go, but you want a guaranteed price in the future for your work.

So, I also provided a table on the right here, so we can see the different types, and we’re going to go into depth on quite a few of these. The livestock, we have the cattle, hogs, and the actual meat, for example. Physical commodities, we’re going to talk about corn, wheat, and lumber, probably touch on all of those. Precious metals, gold, silver, copper. Natural resources such as oil and gas. And then we’ll talk about the financial instruments with special emphasis on fixed income, but equities, interest rates, ETFs, and currencies are also going to be discussed as well.

So, today, we’ve moved beyond these physical commodities and livestock and precious metals and natural resources. We’ve moved into the financialized markets, the equities market, for example. And equity and interest rate Futures have significantly more trading volume than commodity Futures today. And there are quite a few good reasons for that. It’s basically portfolio managers in the financial market trying to, again, support the price discovery process and the valuing of these underlying things.

So, Futures can be physically settled or cash settled. You can imagine getting a thousand bushels of wheat. You can imagine getting, sorry, a thousand barrels of oil. In particular, it’s a classic contract size. You can imagine that now handling that where it gets delivered, that gets complicated. In fact, it’s actually almost easier, we’ve discovered over time, to just cash settle a lot of these, even if it’s a commodity, physical commodities too, instead of giving and delivering a whole ton of a lot of wheat, a specific set of bushels of wheat. You would just agree on the cash settlement.

So the physical commodities, they are kind of generally physically settled, we would say. But there’s a lot to it. There’s the actual storage facility costs, getting the lumber, delivering it, all of that is all part of the process, and we’ll talk about that in depth. But the physical assets are generally cash settled. You can’t physically deliver equity index or Libor, which we’ll talk about, or Cedor in Canada, or Cora as we call it in Canada. Right? SFOR is the successor for Libor, and Cora is the successor calculation for Cedor. You need to actually exchange the cash value difference. So, you have to get the cash value right. You can’t really load up a bunch of Cora onto a truck the way you can load up wheat onto a truck. So, cash settled is the preferred for these financial instruments.

Sides of a Futures trade

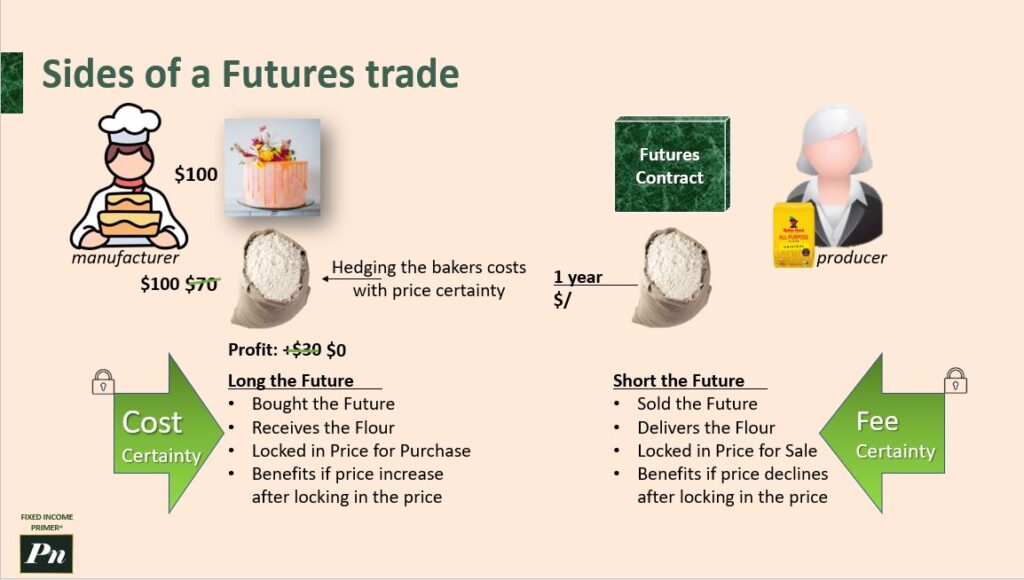

Now that we’ve got the textbook definition out of the way, let’s get into a practical example. And we’ll start with the baker, who is, let’s call it the manufacturer of baked goods. And we’re going to keep things super simplistic. We’re going to say this baker makes cakes, and the only supply item that they need is flour to make the cakes. Obviously, there’s fondant, sugar, all those other great ingredients that make a delicious wedding or birthday cake. But in this case, we’re just saying that’s it. Flour is the only thing they need to worry about, and the cake costs a hundred dollars to make, and this flour supply costs seventy dollars.

Now we’re going to ask, okay, what is the gross profit if you’re selling the cake for a hundred dollars and your variable cost for the flour, the variable cost being the cost that would vary over time based on the supply of flour, let’s say it’s seventy. So, what’s your gross profit here? Just I think it’s a hundred minus seventy, right? That’s your gross profit. So every time you sell a hundred dollar cake, you make thirty dollars in profit.

Now, suppose I don’t want to worry about the variable cost of this flour. Let’s say there’s a war in, I don’t know, Europe, for example, or the cost of flour suddenly goes way up. This baker is going to be suddenly worried about the flour. And in fact, it won’t cost, let’s say, seventy bucks. Let’s say the cost of flour actually goes up to a hundred dollars as a result of quote-unquote macro or external global factors. Flour becomes thirty bucks more expensive. Well, suddenly, this baker’s profit goes from thirty bucks down to zero gross profit. And that could be kind of threatening to the business owner’s goals. And in fact, you wouldn’t sleep very well in that case.

So, this baker has all these worries about creating and capturing market share, making sure that they have a reliable source of clients, customers that keep coming back. They make great baked goods. And now you’re also, as the baker, worried about the price of a commodity that you need to make all these baked goods. It kind of would stress you out quite a bit.

So, introducing a solution for that problem. Imagine you could lock in the price for the flour. So, the manufacturer finds someone who can supply the flour, but on a special agreement. The producer of the flour will come to an agreement through a contract that states and stipulates that they will provide the flour for seventy bucks in a year’s time when you need to replenish your stock of flour or whatever the time frame. Seventy bucks will be the static price. I agree to give flour in exchange, you give me seventy bucks, and we’ll be even Stevens on this. This will be a locked-in price and this is known as the technical term is known as the Forward Price.

Now, I think we made it pretty clear why the baker would like to do this, right? $70. Now it could go up to a hundred dollars, and there’d be zero gross profit. At the same time, though, the producer might be betting something else, that the $70 bag of flour actually might go down to $40. So, if that were the case, this manufacturer is still contractually obligated to buy the flour at seventy dollars, and the producer is still contractually obligated to supply the flour at that price. Even though in the case I just mentioned here, and we’ll show it graphically in a bit, if it was $40, this baker would like to get out of that deal. “Wow, no, I don’t want to continue that deal.” But this futures contract obligates the manufacturer to legally require them to follow through on the contract. So, it’s a kind of a beautiful system because it locks in certainty.

So now we want to touch on, okay, what’s actually the terminology here? We start to get into jargon a little bit, and I think it confuses people. But the producer would be said to be short the future. So, this “short the future” person is saying short is another way of saying “I want to sell it because I expect the price to go down.” I’m shorting the future on trading floors or in finance generally. If someone says they’re short a stock or they’re short a bond, that means they’re not bullish about it. That means they don’t think the value of that asset is going to be going up. They think it’s going down. So, they’re incented to sell the asset now because they would be shorted if they had the asset right now. They would sell the asset. If someone says the opposite, if they say, “Oh, I’m long this asset,” that means they’re holding on to it and they like the asset because it’s going up in value over time, in their estimation. So, if I say I’m short a particular stock, it means I’m selling that stock if I have any of it. And if I say I’m long a given stock, it means I’m holding on to that. Exactly the same logic applies for the bond market and fixed income as well.

And so, back to this particular example, the producer has sold the futures contract. They have to deliver the flour that’s part of the contract, and they lock in the price for sale. And this benefits if the price declines after locking in that price. The futures contract is agreed to because if the price went down, as I said, from 70 to 40, this would be a great profit situation. Gross profit situation. That’d be sixty dollars, right? If it was $40 worth of flour. But sorry, Baker, you agreed to take on this flour for certain in exchange for $70. You would get your bag of flour.

When someone said to be long the future, that’s what we’ve got with our Baker friend here. The Baker bought the future contract. They received the flour and they locked in the price for purchase. And I give seventy dollars in a year’s time in this arbitrary example. And it benefits specifically if the price increases after locking in the price by having gone long the future. And the producer is unhappy, really, because they were betting that the price was going to go down. That’s why they entered into this contract. They went short the future.

Now it is as good a time as any to pause this video. I’m not in this exact frame because obviously I have these two pause symbols on it, but pause the video and explain this whole thing to yourself. Or if you have a friend or family member in the room who’s willing to entertain listening to you explain it, explain what I just explained. And this is actually something really cool. It’s called the Define men technique. Professor Feynman, Nobel Prize-winning physicist, amazing lecturer. You learn a lot in his view by pretending you are teaching a concept to a group of students. It is actually the best way to learn, in his opinion, and I tend to agree. You end up identifying gaps in your own explanation, and you go back to the source material to better understand it. And you organize and simplify, and then transmit it to others. You know, the ideas. And it wires in your brain and understanding, and you’ll be able to better move forward because you now understand it a lot better. So let’s get into the philosophical side now.

Farmers, Producers, Manufacturers and Consumers

So what’s really happening here from a human behavioral level? As I’ve explained before, not in this series but elsewhere, that the time value of money, the value of money today is always greater than at any point in the future. Human behavior says it’s always better to have something now than at a future date. At least, that’s the financial system’s bias assumption that we prefer things now over distant into the future. Futures contracts themselves actually address this other concept of worrying and having enough sleep at night and stress. But what is that term that we typically use for it? We call it risk. We’re managing risk by basically saying, “I’m locking in cost certainty for the production of my goods and services, and the producer is locking in fee certainty that they’re going to be paid.” In this example, 70 bucks in exchange for their product, which is ground-up wheat turned into flour that they deliver to the baker. And that is even Steven’s arrangement that they both contractually agree to. It’s binding. You can’t get out of it. So it creates a system of certainty in a world of uncertainty.

So futures really have an incredibly valuable role in the financial market and in this real-world example. And I’ll explain how this is much more a real-world example than an actual Financial Futures example, but this is a good starting point. And I hope this is locking in your mind as to what’s actually going on, what are the mechanics, and some of the general terms I think we’ve covered here. Basically, this baker is hedging the costs with price certainty around this particular commodity that they need to make awesome, delicious wedding cakes, whatever cakes they do.

So wait a second, what are they? Actually, hedging against what are they avoiding? What are they worried about? What are the risks that they’re taking?

Into account and why they’re entering into this contract? Because they’re worried about it going up to a hundred dollars, particularly in the original example where let’s say there is a global war. Around wheat prices go up to 100 bucks, so suddenly zero gross profit. This is a great deal. The baker then looks “quite smart.” This would be horrible for society in general. I’d be worried about people even having weddings and birthdays or celebrating with cake. Anyway, but one of the side effects would be the price goes up.

So the baker in that circumstance would have at least one thing to be happy about. Now they don’t have to have huge cataclysmic macro events for the price to go up dramatically like that, by the way, but that’s sort of the inherent reality in finance about risk-taking. That if things go bad, you can actually generate a benefit for yourself. If things go well, you can also generate a benefit for yourself. That’s one of the powers of this technology, this financial technology that’s been developed, which is to, as maybe the word, take advantage of a given circumstance to support one’s interests using your predictive powers.

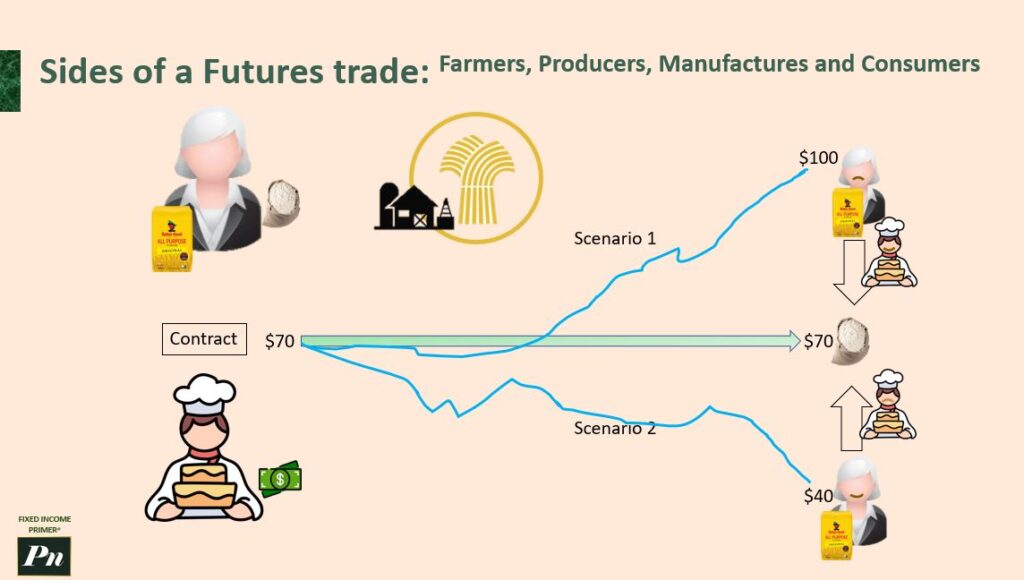

So now, just using the same example but showing it in a different visual style, we’ve got the producer again. They’ve got the flower, they produce flour. The baker has cash, they produce baked goods. They’re going to come into a contract together at seventy dollars. The producer is going to give the flower or the baker. The baker’s gonna give the money to the producer at a future date, right? And so, how do we illustrate that future date? Anytime into the future could be a week, could be a month. It could be often contracts will find are quarterly or a year. But what happens in the interim? Right, the price of that bag of flour might actually fluctuate.

So in scenario one, initially the flower’s price goes down a little bit. So the producer is really happy that that is happening because maybe it’s going to continue to go down and they can provide the flower and get 70 bucks at this point in the future. Right, it’s a pretty sweet deal if that were the case. But in scenario one, look what’s happening. Oh no, oh no, now the producer is not so happy. The price of flour has gone way up to a hundred dollars. So just pause, I’ve kind of already implied what happens here, but think about what exactly, who’s happy, who’s the winner and loser in the scenario? This person who’s short the future or the person who’s long the future. So just pause for a second and think about it.

So in this scenario one, the producer is definitely going to be unhappy with the situation. Now, why would that be? Well, because they have to deliver that flower at seventy dollars value, and they get seventy dollars from the baker when flour in the open market is actually worth a hundred dollars. So the mark to Market, which we’ll talk about what the global or local or commodity price of flour in the general market is, a hundred dollars, and yet you’re only going to get seventy dollars for the flour you’ve delivered to the baker in this circumstance. You’re not happy about that. Now, the Baker, on the other hand, who was long the contract is, in fact, quite happy, right? Because all they had to do is pay 70 rather than a hundred dollars for that bag of flour.

So now let’s consider a scenario. Scenario two: the available wheat fields double or there’s a huge amount of surplus wheat in circulation. And then there’s also the flour production. They have found new efficiencies in technology, and over the last year, they’ve made it a lot easier to convert wheat to flour. Whatever the macro or whatever activities are happening, or maybe there’s been a huge decline in the number of people who like to bake cakes (I highly doubt that, but let’s just say that were the case), then the price of flour goes down. More realistically, there’s a bumper crop, and more wheat is being produced. So there’s more supply of the commodity in the overall global market, and maybe that’s because the weather has been fantastic. It’s rained at the perfect time, the seeds were sown at the correct time, at the optimal time to produce the highest yield of wheat per bushel. All that stuff is contributing to an increased supply of this commodity, and therefore, the price of flour has dropped dramatically. That would be an example. This is also the technical term, might be a bumper crop. There’s more delivery of wheat. I’m from Saskatchewan, so you would know, growing up there, that it was always if the weather was cooperating, then it’d be a great year for the broader community, the economy itself.

So, I’ll just pause for a sec. You can pause the video and ask, “Who’s the winner and loser in this circumstance?” The person who’s long the future or the person who’s short the future, right? So the person who’s long the future is unhappy, and that’s the baker, of course. The person who’s long, this person is now getting flour. They have to pay $70 for the flour. The producer is delivering that flour, and in the open market, it’s worth $40 bucks, whereas they’re getting $70 from the baker in this contract. So, in that circumstance, the person who’s short is going to be the happier one, the one who won in this bet, in effect, or this strategic decision around locking in the price a year in the past. And now, here’s the fruits of your decision. You’re actually really making a great deal for yourself as the person who is short. Maybe you thought you knew all along that there were factors that were going to lead to the price really dropping, right? You had some insights that you felt a few people were aware of, and you wanted, and it’s not insider trading, by the way. I mean, you had insights that were divine, or you think you’re really brilliant and you have these predictive powers, and this bore out in this case.

So now we’ve talked about definitely the producer and manufacturers and their relationship. We haven’t talked about the relationship with the farmer who has the wheat and harvests it at the end of a season. The farmer is actually a really important group to understand too. They have a particular problem when the whole crop is harvested all at once. All the farmers, all at the same time, are harvesting. So suddenly there’s a huge supply of wheat in the market. If you look at it from a simplistic economics demand-supply curve perspective, you would know that that would drive down the price of wheat in the market. We’re going to see this in other examples, including in ancient times relating to olive oil. The price might be appealing for the manufacturer just around September or October, but it doesn’t have to hold all of that wheat all at once either. And in fact, it’s actually a lot easier, depending on who wants to store it, to keep the wheat in a certain location and have these contracts correspondingly obligations tied down to when they get the delivery of that wheat. And so, you can actually, and the great thing about wheat too is it can be stored all year round, so you can time when you actually have to deliver it. So, this demand-supply concern about all the wheat at the end of the season isn’t so big, but they want to hedge their risk if the price goes down. Wheat farmers always are incented to have the highest price for their commodity, and the manufacturer or producer at the flour mill has an incentive to buy it at the lowest price possible. So, this is a counterbalancing risk management tool as well because the price is balanced based on these futures contracts that create a new equilibrium for the value of the underline. So, as it’s hedging of prices and managing the risk, there’s another group of people we talked about, the farmers. We talked about the producer and then the manufacturers. Let’s talk about the consumer because they’re actually very important as well, obviously.

With the baker, you had the wedding cake. Well, that’s actually for obviously weddings, and the price of the cake we said was a hundred bucks. Well, if that price went up too high, they might be disincented from buying a wedding cake or getting another wedding cake, for example. Or the better example I think is looking at cereal. It’s a stable price across the year. Usually, General Mills will calculate out with their financial department, their variable costs, their fixed costs, how much is it going to cost to put this on a shelf, what the competitors are doing for their pricing. All of those factors are consumer-facing issues around what the appropriate price for this cereal is. And that price has to be stable over a longer period of time. And that’s way longer than the real-time adjustments to the price and the of a commodity like wheat, which is used in making Cheerios. So, futures contracts are really essential for then stabilizing what General Mills interests are, hedging the supply costs to deliver to the consumer a nice even keel price over an extended period of time because that’s what consumers demand. Consumers don’t even, you know, inflation is two percent, is happy. But if we see higher inflation, then the consumer is unhappy. And so, all these are factors, and the futures market delivers for that.

Finally, you know, another example would be that livestock market, again securing the prices for cattle. And you go to a fancy restaurant, and the price of a steak is relatively stable over a year, for example. What happens over time? Obviously, inflation, but two percent inflation roughly is kind of the goal. But in effect, the steak is at a reasonable price over a stable price over a longer period than what the financial and supply prices can muster. The supply prices can fluctuate very rapidly, and it’s in real-time over a period of an extended period of time. So, futures contracts act as a stabilizer for the pricing when it’s consumer-facing. So hopefully this way of looking at it is also helpful as a visual format. So, the previous slide and this one together, I’m hoping you locked in this knowledge. And might as well say it again, explain this to a friend or family member, and you’re going to feel really good and you’ll be ahead of the game.

Futures run deep in human history

Alright, so now let’s take a look at some clay tablets. This is a clay tablet from Mesopotamia, which is between the Euphrates and Tigris River, which is actually modern-day Iraq. Ancient civilization, and what they were doing here is quite remarkable. I called it technology earlier, and when we think technology, we think computers, all that stuff. Now, financial technology like this has been around for over 5,000 years. This tablet stipulates a forward contract, and that is the precursor to futures contracts. Farmers can agree to sell their crop in the spring to be sold in the fall at a set price. The farmer is protected by any uncertainty in terms of the outcome of the price, but the other side of the transaction could be harmed or benefiting depending on how that season goes. So, this is exactly what we just talked about in the previous section. This was exact and this was happening 5,000 years before any of us were around. And so, let’s also just reconnect to why it’s called a derivatives contract. It’s because you’re transacting cash in exchange for the underlying, or you’re basically making a speculative position.

You’re setting up a price for a commodity, and you’re using the real market price of that commodity at the end of the period to determine how much you won or lost by in terms of your committed bet at the start of the contract. These farmers would have these clay tablets to lock in the sale of their crop in the spring for that coming fall at a set price, regardless of how the market price for that crop changed between the spring and the fall. Right, they’re locked in. They have to pay the specific price they agreed to. Now I’m definitely not going to ask you to pause the video now and use this slide to explain futures because I don’t really get what this is, but archaeologists please say that this is all accounting to help describe the contract that the farmer and whoever was the counterparty agreed to in this contract. So, it’s kind of neat. So, one of the subconscious insights of all this is if people 5,000 years ago were doing futures contracts, then we should be able to figure out how these things work as well.

Thales of Miletus

Continuing on in a sort of historical pathway here, this is a painting in the Vatican. It’s called the School of Athens. In the middle of this painting is Aristotle, and in fact, he is on a ton of textbooks. If you ever take philosophy, you’ll have seen this depiction before, and it’s showing sort of a court of all these famous philosophers are in here. And one less famous philosopher is named Thales of Miletus, and that is this dude here. We believe he was a generally poor philosopher to start. He wasn’t very successful in being a philosopher, it turned out. But he used another skill, and it was the skill of forecasting and predicting. This he was able to predict all of the harvest and get a good sense of weather patterns. And he had a fine-tuned means of understanding when would be an exceptionally good autumn for the olive harvest. So, Thales, as a result, made agreements with the local olive press owners. Okay, so what’s this thing on the right? It is an olive press. If you actually think about it for a few seconds, you’ll get it pretty quickly. You put the olives right here, and this stone rolls over the olives, crushes them, and then the olive oil comes out down here. And obviously, you kind of go in a circle. So, this is an olive press. Point here though is that Thales went to each one of these, probably fairly expensive to build local olive press owner companies, I guess you could call them. And he made agreements with them to deposit his money with them to guarantee him exclusive use of their olive presses when the harvest was ready. He basically blocked off their calendar and said, “Hey, I want to own the rights to this olive press during the autumn season.” Thales successfully negotiated lower prices because the harvest was in the future, and no one knew what the harvest would be like, whether it be good or bad that fall/autumn. And because the olive press owners were willing to hedge against the possibility of a poor yield, they entered into these agreements with Thales. And when the harvest time came and the harvest was good, many presses were wanted concurrently. Right, everyone’s like, “Alright, we got surplus, we got a bumper crop of olives, we gotta get them pressed quickly or else they’re gonna go bad.” And so, there was a huge demand for these olive presses all at once, and Thales was like, cross his arms and was like, “I’m pretty smart now, aren’t I?” He provided access to these presses, but at a very high rental rate to the olive producers. And he made an amazing amount of money in that era. I guess a drachma, probably a Greek drachma. Made a lot of money as a result of cornering the olive market, doing a futures contract with the olive press owners, and finding out a little niche, little spot, and to become incredibly wealthy. Not a great philosopher, but a great business person, you might say.

Dojima Rice Exchange

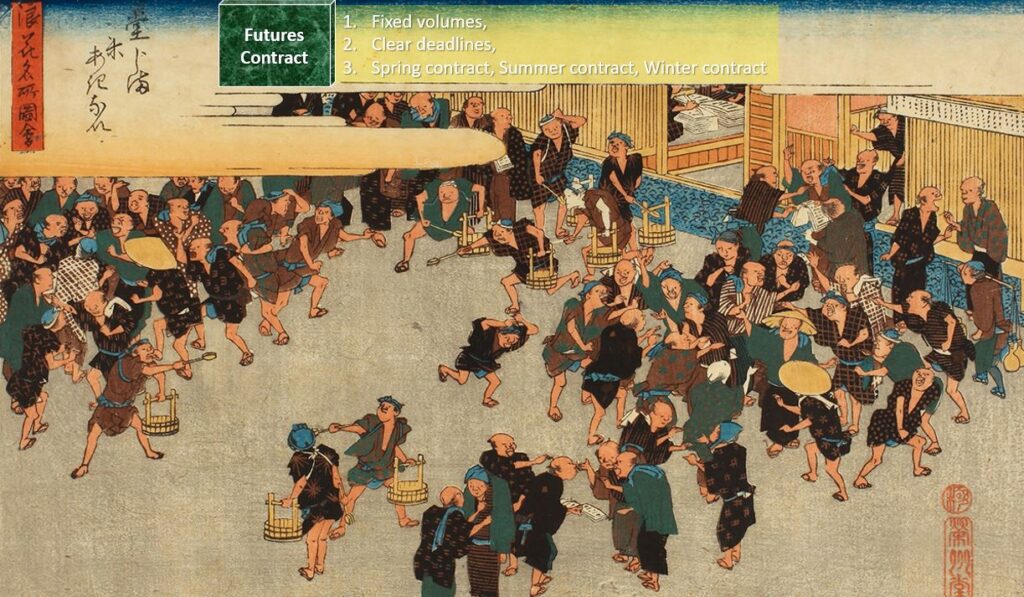

Now I promise to get onto a topic that seems a little more relevant to modern-day. But the first futures exchange market was the Dojima Rice Exchange in Japan, which was initiated in the 1690s. Originally, it was about landowners who were involved in farming and selling their rice. Farmers made money by selling warehouse receipts for the rice and transferred excess supplies of rice to Osaka and Edo merchants who bought these receipts would lend money to farmers in need in return for future rice crops. So, they started to create a kind of financial system in that way. But what really kicked things off was in 1730, futures trading started at the Dojima market with the goal of preventing long-term declines in rice prices. This allowed farmers to hedge against price changes between harvests. They wanted a guaranteed price. And so, you can see that what I’m about to describe is intuitively you should say, “Okay, this is a futures contract.” Dojima rice futures markets operated on all the same modern rules of futures trading. So, they had a fixed volume for each contract, they had clear deadlines for each contract’s expiry, and there were specific contracts. The spring contract was from January to April. There was the summer contract from May to October. And then there was a winter rice contract from October to December. And these were set tranches where those contracts existed. So, all these transactions were also entered into a book registration system, and that listed also the names of the parties, the rice volume of the futures price as well, and the delivery dates were all recorded. And here’s the key: transactions were actually settled in cash without the need to physically deliver rice between the two counterparties at the end of this trading period. And so, this was how the rice contracts really took off and futures trading really took off from Dojima.

Another really interesting thing is that samurai were paid in rice, and after a series of bad harvests, samurai realized they needed to be paid in something that was stable for conversion. And so, these futures contracts acted as a convertible to coin points as well, and they created a broader market in that sense. Then samurai, by the way, I was a big fan of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, so that’s probably why I’m mentioning this. Academic textbooks also mention this, but samurais were hereditary military nobility. It was a medieval and early modern Japan from the 12th century to their abolition in the 19th century. And they were basically well-paid protection teams or warriors. And anyway, so that was just a side note. I thought it would be fun to talk about samurai for a sec.

Chicago Board of Trade

Something further on happened, and it happened in Chicago, United States, where the concepts around the Dojima Rice Exchange were brought, imported into the U.S. and used a lot of ideas from Japan were exported. And one of them was indeed futures trading, in my view. And the Chicago Board of Trade was established in 1864, and it was all centered around futures contracts. And these contracts were based on grain and livestock. It started a trend that saw these contracts created for a number of different commodities, from livestock in particular, and particularly wheat as well. And a number of futures exchanges were set up in countries around the world. This was the first one, the Chicago Board of Trade. I mentioned this now. You can actually see in this architecture there’s this guy holding some wheat, and this person holding some corn. And you can bet that corn and wheat futures contracts were indeed traded at this CBoT. It’s Chicago Board of Trade, is how it’s probably referenced. I don’t hear a lot of people saying CBoT. All in all, there’s a long historical trend that goes all the way back to, well, the Mesopotamian, all the way back 5,000 years, Thales of Miletus, to the 19th century in Chicago. And we’ll see what are the mechanics. Now, let’s dive a little deeper into a more complex example of futures trading and see if we can better understand this concept.

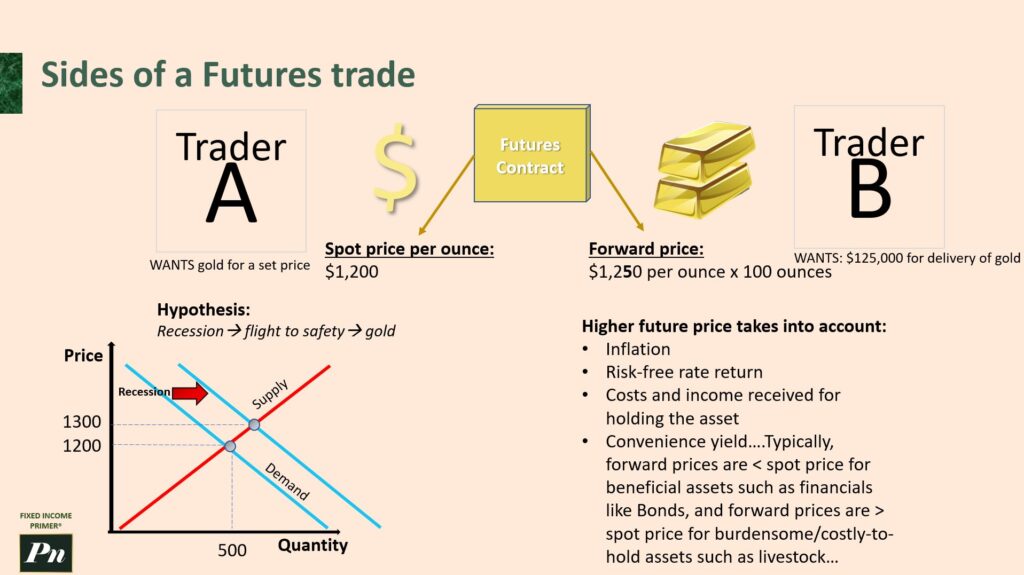

Alright, so now we’re going to talk about another example, this time, it’s a futures contract related to a precious metal, and that metal is gold, right? So, Trader A has a hypothesis, and that hypothesis is the following: that the economy, in this example, is going to be entering a recession. And when there’s a recession, there’s going to be also a flight to safety. And that means people will take their capital out of the equity market instead of these speculative stocks that they’ve got. They want to move their money from those stocks, convert it into gold because precious metal gold is a place that can be relatively safe against major shocks in the broader economy, etc. So, the thesis is gold is going to be vogue. It’s going to go up in value.

Gold Example, Futures trades

So, Trader A has that bias, and just to ratchet it up a bit and sort of suggest there’s more to learn in terms of how bonds, GDP, and economics all intertwine, I’ve got this visualization. If you look in the description of this course, you’ll be able to find my other courses on bond math, and we touch on the bond yield system in greater depth. But here, I want to just talk about what exactly is going on with this Trader A’s hypothesis.

So, Trader A basically thinks the business cycle is right here, approaching a new recession. And he or she notes that the bond market and the yield curve is showing signs of a butterfly shift, which is indicative of a recession. And that is where the short-term yields on bonds, the three-month bond and the six-month and one year, are really bowing downwards, they’re pushing down, shifting downwards, and longer-term yields are slightly lower. And so, you’ve basically got from an inverted yield curve situation, which is this phase three where there’s basically an overheated economy, the yield curve will start to invert in that circumstance. Now you’ve got a butterfly shift. We think there’s a recession happening. The bond market’s going to behave this way. The flight to safety in this Trader A’s view is people are going to start taking capital even out of fixed income and put it into gold.

And maybe, you know what? I’m just going to keep going here because I think this is so cool, right? So, you’ve got your yield curve. So, in a growing economy, there’s a natural shape of the yield curve. It’s upward sloping. And then, as expansion starts to happen in the broader economy, you start to see different behaviors. People start shifting their investment into the longer-dated bonds because they think it’s a safer plot space. And what happens here is when yields go down, prices go up. And when prices for bonds go up, that’s indicative of demand for those bonds has gone up, right? Because if you think of demand, if people increase demand for something, the price correspondingly goes up. And here, the yields have correspondingly started to shift downward. And then, you start to really see an inverted yield curve. So, the entire macro bond market, institutional specialists, etc., are all sort of coming to a consensus, in effect, although there are competing views. And there’s but the actual way that people spend their capital, allocate their capital is indicative of what they think. And so, that’s why the bond yield curve is such a powerful tool for people to understand how the broader economy is doing, particularly the difference between the three-month and the ten-year in the US, is the biggest, most widely used metric. So, you see an inverted yield curve when the three months yield is actually higher than the 10-year yield.

And then, we got this butterfly story, right? What would you say? I said this is a recession, and a recession is happening for sure-ish. And then, in the deep recession, the yields are driven down by a central bank dropping the interest rates or policy interest rate in Canada or the FED fund rate in the US, pushing it down. And other countries have their own term, but it’s basically the central bank’s interest rate pushes that down. And then, you start to have a normalizing yield curve as a result from going from the butterfly-shaped, which is right here, down to a return to a sort of normal-ish, and then back to the bottom of the trough, which is really one. I guess you could put the one here, and then recovery here, and then peak up there.

So, that was a bit of a tangent, but back to what Trader A wanted. Why is the Trader A person so bullish on gold? Bullish meaning they think the price is going to go up. Well, let’s think about it from a demand-supply way of thinking. So, this is a price and quantity relationship here, and bonds, in particular, or gold stocks, all behave under the same rubric of this demand-supply curve. Finance being a sub-discipline of economics, it makes a lot of sense that this is useful. So, what happens here is that this Trader A thinks that with regards to gold, the price is at $1,200, and that’s the current demand. The thesis is because there’s a recession, people are going to increase their demand for this precious metal, pushing the demand curve this way, pushing it this way. Supply is relatively static in gold, and so as a result, the demand curve pushes this way, pushing the price up. And that’s really the reason this Trader A thinks, “Okay, I should buy positions along on the gold future.”

So, let’s say the spot price per ounce is at $1,200. And that’s per ounce. Then, we’ll go into a forward price agreement with Trader B. Trader B says that there is a carrying cost of $50 bucks per ounce, and there’s a contract for 100 ounces. That’s the futures contract preset requirement that you have to take 100 ounces of gold. Remember, this is per ounce. So, Trader A wants gold for this set price here, commitment for this nice price, which is a good price for them. Trader B says they want the forward price that is agreeable in the marketplace, times 100 ounces. And that’s $125,000 for the delivery of this gold, which again Trader A wants to take his or her cash and turn it into physical gold because Trader A is thinking that at $1,200, they will get the equivalent of $1,300 worth of gold at a future date, right? Because the market price, this trader is anticipating, will go up. So, the value of this commodity will go to $1,300. But the spot price that they have to give to Trader B is actually only the forward price that was agreed to in this futures contract. It stipulates that the forward price is $1,250 per ounce.

Certainty of Winners & Losers in Futures

So, Trader B is going to, at this upgrade upon date, receive $125,000 in exchange for 100 ounces of gold that the trader then takes. And again, if this is $1,300 in value, the actual gold goes up in value, then Trader A has made a nice profit. Now, in this modern context, I can see how this might be a little confusing because wouldn’t it make sense then actually for Trader B to just ship away a little bit of the gold, take away an equivalent ounce or so in order to deliver the exact amount that Trader A is getting in terms of a swap from cash to gold? And no, that doesn’t make sense in this futures contract land. This is the whole point of the futures contract, as we’ve talked about it way back from Mesopotamia to the Dojima Rice Exchange, all of that. I think now, hopefully, you get that this is a bet on where the price of this commodity is going to be. And Trader A wants the certainty of a predetermined price or a predetermined amount of cash, giving cash for the asset when the asset has gone up in value. Trader A is going to be really happy. If the asset has gone down in value, Trader B, plus shorting, is going to be happy.

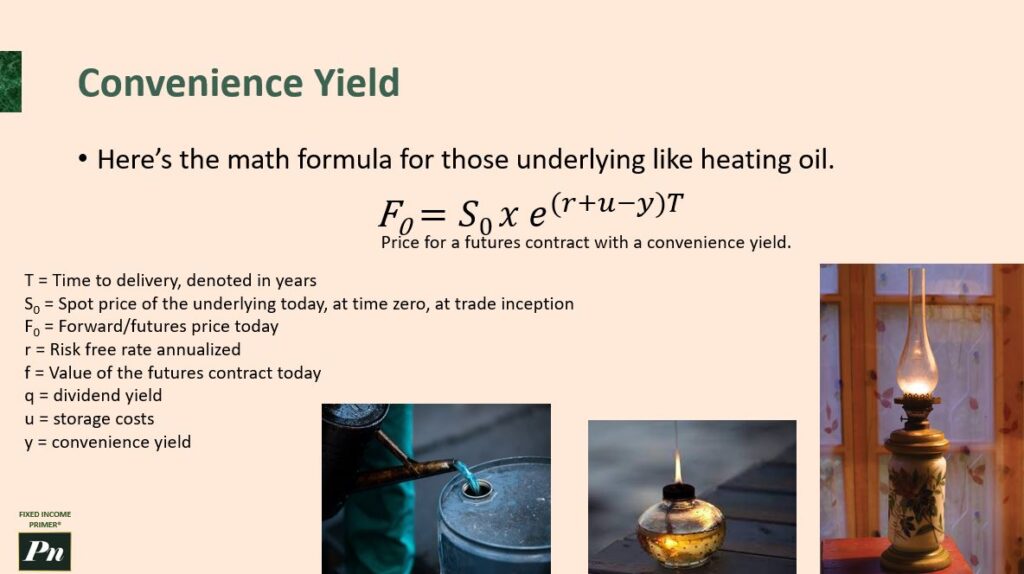

And so, here I just want to touch on the concept of that carrying cost. Higher future prices, a higher future price, in the prior example with the baker, the $70 bag of flour, there was the future price was $70 as well for simplicity. Now, we’re just sort of adding a little more complexity. This is that carrying cost, and that carrying cost here is that $50 extra that was negotiated as part of the forward price. So, what does this additional $50 really account for? Well, things like inflation. The contract might be a year long. In a year’s time, inflation, in a normal stabilized period, would be 2%. That’s the actual target inflation that monetary policy, global central banks have. There’s also the risk-free rate of return. I could put this capital elsewhere, and I would get a return that would be similar to $50. So, you need to pay me for this risk-free rate. And then, the cost and income received for holding the asset. So, this is the more formal convenience yield component, right? So, it’s the implied cost, and we’ll be using that word “implied” a lot. It’s the implied cost of holding a physical commodity, such as livestock, or even a financial commodity like a bond, instead of actually holding the corresponding futures contract.

It’s the underlying that you are in possession of, and it is this extra return one can earn from holding the physical commodity instead of the futures contract. So for livestocks, futures differs from bond futures in that the underlying asset is obviously a physical commodity, whereas bond futures are based on a financial instrument. And this means that in the case of livestock, the physical animal must be delivered upon expiry or expiration of the futures contract, whereas the bond futures typically settle in cash. And in this example of gold, we’re saying that it would be settled in the physical gold, but we’ll show later that it can also be settled by cash. But basically, in both, in all these examples, the convenience yield is an expression, and it’s associated with things that are more difficult to hold on to. Like, as you can imagine, you’ve got to feed the livestock, the cows have to have be sheltered, etc. So it’s typically a lower convenience yield to manage livestock than that of bond futures.

So another way to express this is to say that the convenience yield is basically saying typically forward prices are less than the spot price, typically for beneficial assets such as financial instruments like bonds, and forward prices are typically greater than the spot price for burdensome or costly to hold assets such as livestock and, in this case, gold. Because let’s face it, gold is pretty and all, and if you leave it out in the sun, apparently it will melt a little bit if it’s pure gold, and it costs to store, and you’d probably need to get a vault for it. I think you probably need to get security for it. All that’s sort of a pain in the behind, I guess you might say. And so how do you quantify that? Well, you have the carrying cost minus the convenience yield that the holder of this commodity gets 50 additional dollars to justify entering into this contract, sweeten the deal, and make this futures contract a reality.

Novation, Cancelling-Out

Right, so let’s ratchet up the intensity here. We’ve got Trader A and Trader B, again. Trader A wants cash, Trader B has gold, and there’s a futures contract at stake here that they want to agree to. So let’s just say in this example, as we showed in the prior slide, that convenience yield, the 50 bucks, is inserted in there. So the long futures position ends up being 125,000 for a hundred troy ounces, which is the metric for the COMEX, and the Trader B is short the future. So this Trader B has, quote unquote, sold the future contract, right? Because when you’re shorting something, you think the price is going to go down, you want to sell that thing, you want to get rid of it because you believe the value of that asset is going to decline. And if you think something is declining in value, you want to convert it into another format, i.e., sell it, rather than hold on to it. Whereas the long position, again, as we say, hold, you want to hold it, you want to buy it, you want to buy more of it if it goes up, enjoy the fact that that asset is rising in value. Okay, so this is the setup.

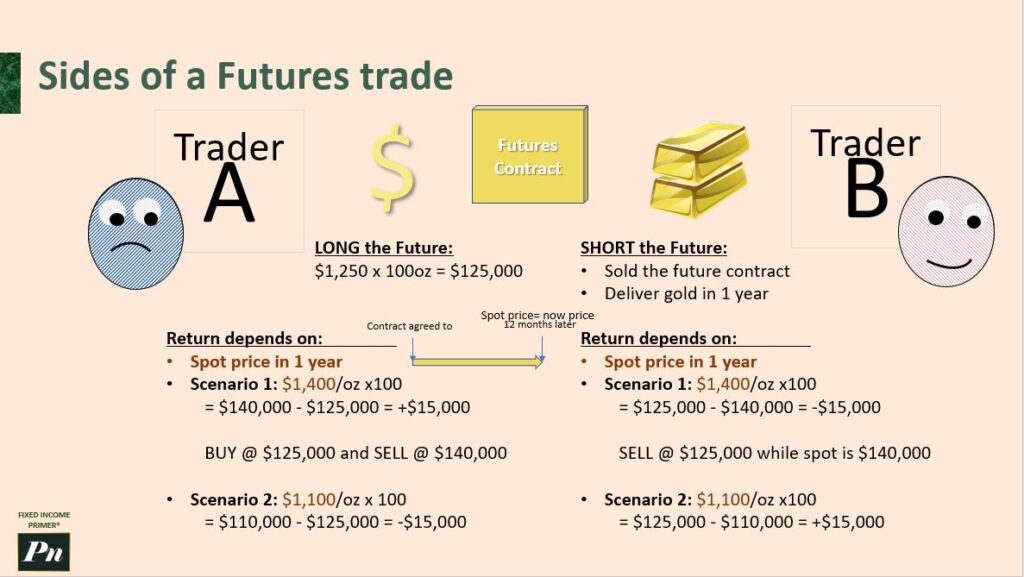

Now let’s think a little more, and you’re going to have to do a little pause of the video and then open up the Excel and start using Excel to help express our understanding. The return depends on what things, the return is everything in the sense that it helps to determine if they’ve done well or not. And let’s just say this contract is a year from now, it’s a full 12-month period futures contract, right? As I said, deliver gold in one year. So what’s the spot price? This is key because what’s the current market price is super critical to understand whether or not there’s a who won this in this futures contract and who’s lost in this futures contract. So you swap the money for the gold, right? You gave them the gold, Trader A now has the gold, Trader B now has the money. What’s the cash upon expiry date? What, how much does Trader A have to provide? That’s 125,000. So now we’ve got the spot price in Year One. So we’re now coming to the point in time where we’ve got to give the gold. What’s the value of the gold? The spot price for the gold is now 1,000. So what’s the notional value? So pretty straightforward here, you would just multiply this by the contract unit multiplier, right? So that’s the notional value. And what’s the difference between this value and this value? $15,000. So in this case, Trader A made $15,000. Right? So the gold and the money switch hands, and this was the scenario. And we have $15,000 up for Trader A and $15,000 down for Trader B.

And let’s look at the logic of this. This is only possible because Trader A buys at $125,000, which they were locked into again a year in the past, they were locked into, committed to buying for that price. And then they, in the real market on the spot price date one year later, they possess what is in effect $140,000 worth of gold. So they can turn around and realize this $15,000 profit if they were to turn around and sell it. Trader B is not so happy, why? Because they sold gold with the assumption that it was going to go down in price. They get $125,000 in a year’s time, but if you can go in the real market and actually sell that same gold for $140,000, but they can’t do that. They actually have to, again, this whole thing has to happen because the futures contract stipulates that the money and the gold have to swap owners. And so Trader B is indeed in a sad face sort of mood because if they were to realize this loss, in other words, if they were to go in the market to buy up gold anew, they would actually see a $50,000 gap between the money that they got from Trader A and the money they need to actually buy the equivalent amount of gold in the market, the 100 ounces of gold in the market.

So now let’s do an Excel for Scenario Two. Alright, Scenario Two is $1,100. In this parallel universe, let’s say we locked in the deal at $1,250. But in this case, a year passes, and it turns out that the price of gold has gone down. So let’s open up Excel and do that exercise.

Okay, in Scenario Two, we had $1,100. So now, let’s simply calculate the notional value. It’s going to be this times our contract unit multiplier to get our notional. And then, to get the difference, make sure you get the polarity correct. It’s the notional value at one year’s time minus the cash upon delivery amount that has to be given. Trader A, this is all from the perspective of Trader A because they’re $15,000 up and now they’re $15,000 down. Kind of a bummer.

So now, Scenario Two, as we just calculated, it’s $110,000 minus $125,000. Trader A is not in a happy mood, and Trader B is in a good mood because they’re now up $15,000 in terms of their return. They got $125,000 at the end of one year when the actual value of gold one year from the start of the contract is $110,000.

Now, let’s flip the switch here and say that Trader A is in possession of gold right now. They’re going to enter into a Futures Contract with Trader B for cash. Why would they do this? Well, they have a hypothesis. The same environment of a recession is expected, but Trader A has a new interpretation of how that’s going to play out. They believe there will be monetary and fiscal loosening. In other words, the central banks around the world and in their country, in particular, are going to lower interest rates, making it easier to borrow. The government’s fiscal decision-making is going to involve spending more, injecting more capital into the broader economy, leading to an economic surge in discretionary spending. So, buying stocks, buying luxury items, people who are already well off are going to spend more and stimulate the stock market, driving the value of even growth stocks and value stocks upwards. So, that might be a hypothesis that is viable.

So, how does this impact the price of gold? Well, everyone realizes that during this recession, things are going to actually become more attractive to invest in. People are going to put their capital into stocks and bonds, but particularly stocks, now because of this firm hand of the central bank and the fiscal decision to increase spending. So, you want to catch up before the inflation catches up. The demand for gold is going to fall because people who have gold are going to take their capital out of gold and convert it into stocks, let’s say. Trader A, who has gold in their possession, shorts the future because this person has this hypothesis just highlighted here. So, they’re going to deliver gold in one year’s time, and their bet is that gold is going to fall in value over that year.

Trader B has the opposite view. It’s a recession; therefore, the default assumption would be people go into flight-to-safety mode and they put more into gold. They buy up gold, increasing the demand for gold. So, this person takes a long position, again with that $50 convenience yield.

Let’s see how this turned out. The return also depends on the spot price in one year for Trader A, same as usual. The activity happens, the swapping animation is a real thing, it went and happened sweet. So, Scenario Three, wow, overshoot on this one. It turns out that Trader A was even wiser than it even went lower than $150. It’s now a thousand-dollar spot for gold. Everyone’s just completely given up on gold. All those YouTube channels and other advocates of gold, who, by the way, have an ax in gold, right? They have a position in gold and they want to tell you that gold is the most exciting thing you should ever buy or Bitcoin is the most exciting thing that you should ever buy. And because they have a vested interest in the price of gold going up or, for example, Bitcoin going up, if they are someone who’s big on Bitcoin, they will make any possible argument to justify convincing you to go and buy those commodities or securities. And that’s the example, you know, if it’s a rainy day, why don’t you buy some gold? You buy gold because, you know what, people are in a bad mood. It’s cloudy, and this will cheer them up. Um, it’s a sunny day, you know what, gold would be good. Crops are now getting spoiled. It’s too hot, sunny day. The entire global economy is going to shrivel up in the sun. So, let’s buy some gold. It doesn’t really matter, right? For them, they just will generate any argument to justify it. And more sophisticated arguments like the BRICS countries, for example, are de-dollarizing, and we’re all going to return to the gold standard. So, you should get gold, you should pawn your wedding rings, etc. Anyway, that’s just a bit of a tangent. Let’s focus on this. It’s kind of funny, though. Those folks are now really disappointed and have egg on their face or whatnot, and they feel bad. But they, by the way, are going to continue to have an ax to grind in gold. That’s… And so, the difference is $25,000 for Trader A. What a great move, a good bet, as it would be stated, or good speculation. And it’s paying off significantly here. They might call themselves “smart,” but in truth, there are a lot of external variables that Trader A had no control over, and the predictive power is something that no human can really have. But hopefully, they’re smart enough to get that they’re not that smart, and they don’t have that immense predictive power, that this whole hypothesis completely played out perfectly for them. Doesn’t mean that it’s going to work in the next scenario or the next scenario because future events tend to defy expectations. So, you got $125,000 out of this deal.

Trader B realizes, “Ouch, this kind of isn’t that great.” You know what? How do you want to actually settle this contract? Instead of the swapping that we saw out there, why don’t we do something different? Trader A realizes this too and figures out, let’s not bother moving the gold around. Let’s settle in cash. And this is a huge deal because if you don’t have to physically move the gold back and forth based on how the contract is structured, you’re obligated to deliver physical gold at the end of the contract. Instead of doing that, why don’t we just cancel out these parts and just give Trader A $25,000? Trader B gives Trader A $25,000 if it went the other way. Trade A, you know, let’s just pretend $25,000 that way back and forth, just settle in cash. When we’re talking about this, it’s not just gold futures that we’re talking about. We’re talking about livestock futures, hog pork futures, corn wheat futures, lumber futures, silver, copper, oil futures, gas futures, equities, fixed income, interest rates, currencies, ETFs. You name it, futures contracts. They realize you don’t actually have to swap back and forth the physical commodity. And there are stories of people who had to, you know, they didn’t do this cash transfer agreement, and they had to accept physical delivery of cattle, but they had no intention of taking on or barrels of oil, like, “Hey, where do you want me to give you your thousand barrels of oil?” Oh dear. Most people just do this settle-by-cash thing that we’re going to get into detail about. It’s really exciting and a huge step forward in this futures trading innovation.

Okay, so now let’s ratchet up the intensity a bit further because what we just realized is that you could settle for cash, and you can do a lot more that way. And you don’t have to worry about gold flying around all over the place. So let’s get into the details of how this works.

Let’s say Trader A enters into a long position of 155,000 futures contracts. Trader B wants to short because, again, I think the price is going down. But they have to deliver gold in three months. A lot of future contracts on exchanges are three-month contracts. For example, remember the Dojima example where they were doing seasonality? So spring, summer, winter contracts. Similar idea.

So this is then the situation. Trader A has entered. One month passes, and the market price, the spot price, the current price one month into this thing is $1,650. Trader B can sell their stock of gold that they have for $165,000 rather than wait an additional two months and get that $155,000, right? They’re not in a good spot right now because of that. They’re not gonna… They’re not feeling… They’ve got a sad face, is what I’m saying.

Now, what could happen actually might be a better deal. Where Trader B convinces Trader A, “Hey, how about you short this position? Because look at where we are now, it’s $1,650. There’s no way it’s going to go any higher. So why don’t you short that position?” Trader A laughs at first, “What do you mean there’s no way it’s going to go higher? Maybe Trader A,” he says, or she says, “It’s going to go to $2,000. There’s no way it’ll ever go to $2,000. Is that what you’re saying, Trader B? Come on, I think it could go higher.”

Then Trader A kind of walks away, reads some articles, and thinks about it a bit further and says, “You know what? Actually, you’re probably right. It is probably going to go down.” So Trader A then shorts the future in coordination with Trader B, the futures contract to deliver gold in two months’ time. And Trader B is long this position because they’re going to receive $165,000 at the end of two months in this scenario.

So, as per the normal and “painful” way, Trader A, the first contract, the three months has elapsed, and the gold arrives for Trader A, and the cash goes into Trader B’s pocket. Same deal with the second contract. But wait a sec, what just happened here? Basically, Trader B got $155,000, Trader A got $165,000. So the net of those proceeds is really just $10,000, and that just goes right to Trader A.

But what we also did was this expansive thing of delivering gold to each other, physical gold. We swapped gold. What was the point of that? It’s actually almost silly when you think about it. So netting out, thanks to the standardizations of future contracts on exchanges, is a really powerful tool. We don’t actually need to physically settle these. We can just net the difference of what our two positions are and walk away just with the cash transaction. Because, again, these contracts are binding.

You enter into a futures contract, you have to settle. You can’t walk away from it. And the exchange, whether it’s the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, the New York Commodities Exchange, the TMX in Toronto, Montreal, and Canada, or elseag, the London Stock Exchange Group in London, or just listing all these exchanges, it depends which exchange actually creates and manages these futures contracts.

So, the COMEX one that was gold-relevant was for the New York Commodities Exchange. They managed the futures contracts for gold that I’m referencing here. These folks create and manage these futures contracts, standardize them so that you can’t walk out of them. And if someone were to default, there’s always going to be someone else with a futures contract that could fit the bill. Someone has an ax to grind, they think it’s going to go down, another person thinks it’s going to go up. You can match these people in an exchange, so it becomes a more sophisticated and kind of beautiful system. A system where you realize, “Hey, wait a sec, you didn’t need to swap the gold between each other. All you needed to do was net out this $10,000, give it to Trader A at the end of this three-month period.” By having these two contracts live, they net each other up, and you get the $10,000 to Trader A, who was correct in their bet. And so this is where futures becomes kind of a speculative tool.

So let’s actually talk about novation of contracts. If neither party wants to physically deliver gold, they don’t need it in their manufacturing, they don’t need gold in any way, shape, or form, then you can enter into a contract such as this. You can’t rip up this contract, so it’s as real as an actual physical delivery of gold, as the same example here. I’m just saying the market price, let’s say, goes down. So in this case, Trader A is concerned because they’re going to be paying $155,000 in three months’ time to Trader B, but the gold now is only worth, a month later, $145,000. So they enter a kind of canceling out deal here where they short the future and say, “I will give you gold, you give me $140,000. I’m willing to accept that.” And so what happens is you net this out. Again, in this case, Trader B is successful.

Neither party actually owns physical gold. Let’s pretend actually just forget the whole gold symbol at all. There’s no gold being exchanged, but they are in the futures gold contract. They have netted out the proceeds, and $10,000 is awarded, yay, to Trader B in this circumstance.

So this is really a process of novation, and what enables novation is that really, in an exchange, this whole Trader A, Trader B relationship is kind of exploded. You don’t need a Trader A and a counterparty. Trader A doesn’t need to ever meet, know, or converse with Trader B or negotiate with Trader B or anything like that. And we’re going to show how, in fact, that whole construct is just an educational means to explain futures contracts.

Now let’s get a little more sophisticated and ratchet up the complexity a bit further. So if it works for Trader A and Trader B, novation can really work for hundreds and thousands of traders or anyone who wants to take an opposite position. They’ll find someone to match them with on an exchange. And that’s the key with novation. It’s really the process by which traders do not actually interact with each other at all but, in fact, settle these highly standardized contracts on an exchange that the futures contract is hosted at.

Let’s take this to the next level. We’ve got the same two traders as before. We’ve got Trader A and Trader B. So we start with the market price for any commodity. It could be aluminum, it could be corn, it could be bonds. It doesn’t matter. This is just an example. But let’s say this asset on day one is $20. So Trader A thinks it’s going to go up in price. They don’t want the underlying asset. They want to enter a futures contract. They don’t care about delivery of aluminum or whatnot. So they enter a long position of $20. And who do they have to do that with? They have to have a counterparty. Well, conveniently, Trader B is available, and they’re short $20. They think that the price of whatever this quantity is is going to go down. So that’s great. We’ve got one contract out in the market right now.

So here’s the key thing, right? If it’s $20 long, then Trader A is saying, “I agree to buy this asset in three months’ time at $20.” If you’re short, that really is another word for sell. “I agree to sell this asset in three months’ time for $20.” So here’s where things get interesting. Day two, the price of this asset is now $24. Okay, Trader A is probably thinking, “What is this good for Trader A or bad for Trader A?” Pause the video, think about it, and then unpause. So it’s definitely great for Trader A because the price has gone up. And as I said, this is the reason you go into a long position because you think the asset’s going to go up in value. Trader B is thinking, “Darn, this is not great. Um, what should I do?” It’s a situation where I’m now in a loss of $4 already. Trader A says, “You know what? I want to take out my profit right now, and I’m going to sell. I’m going to take the opposite position. I’m going to short at $24 because I want to take out the profit.” Trader B says, “I’m not interested in closing that position, right?

Because that’s not in my interest to take a long position on the $24. I don’t think the price is going to go up any higher.” Trader A is short $24, but that contract isn’t fully complete until there’s a counterparty that takes the opposite view. And now we’ve got Trader C who takes a long position. This is a third trader. There could be hundreds of traders, and in fact, thousands as well. But here we have Trader C takes the long position on $20 at $24.

Now it’s day three, and the price has gone up further to $28. Alright, so day three prices, as I said, Trader A’s closed out. Trader B and Trader C, maybe they want to take an opposite view, maybe they want to trade together through the intermediary of the futures contract and through the exchange, not talking to each other or interacting with each other in any way. So Trader C actually shorts at $28, and that’s perfect for Trader B because Trader B happens to want to close out their position, and they can only do that by going long at $28. So they’ve canceled out their positions. They can’t have two shorts or two longs or more shorts than longs. They have to have an equal amount in order to actually close out their positions.

Trader A has Trader B’s hats, and Trader C has now, let’s say, three months have elapsed, and let’s pretend the price stayed at $28 for that period, or it lands at the three-month mark at $28. So Trader A is going to get $20 for an asset that’s actually worth $28. Now they have an asset that’s worth $28, so their profit is actually going to be $4. Why is that? Because they took a short position where they have to deliver the asset for $24. So all in all, they are up $4. Trader C, same story. They took a long position of $24, and the asset went up to $28. So they have an asset that’s worth $28 in their possession, and they took a short position at $28. So all they do is they hand that over, profit or loss in that circumstance. So their total profit is $4. Trader B, on the other hand, they took a long position at $28. The current asset price is $28, so they don’t see any profit from that. But they shorted at the start with Trader A. They are the ones that deliver the $28 asset to A, and they then lose $8 in this whole deal. The key here is that there are three traders here, but you can have thousands upon thousands of traders because Trader A could do a deal with Trader G. Forget the alphabet. There’s not enough letters. There’s basically all these thousands of people that are taking opposite positions from others, and they’re speculators in terms of the underlying asset’s value. They think it’s going to go up or down. If you can find a counterparty, and by the way, when I say find, I’m not really being correct when I go to Futures exchange.

There are Futures contracts out there. The exchange is the intermediary, and we’re going to get into more depth as to how that actually works in a sec. But the key lesson here is that you don’t have to have the underlying asset to be engaged in Futures Trading, and as such, Futures Trading is a large speculative market for many people. There are also hedgers. We’ll make some distinctions about who participates in this market, but there are a lot of participants who are taking basically bets on the future of a given asset, and they’re not trading the underlying asset. They’re making these positions, they’re opening and closing positions on the asset to try to make profits. And from a philosophical perspective, the financial purpose of this is that in their participation, they are providing what’s called price discovery. They are providing the market with an understanding of how this asset should be priced in real time, and they’re committing their real capital to it in the service of their own self-interest, which is to win or lose these bets. They obviously want to win those bets or speculative positions, but in that service, they’re also providing more data points for what actually the price should be on an asset and informing decision making.

Forwards versus Futures contracts

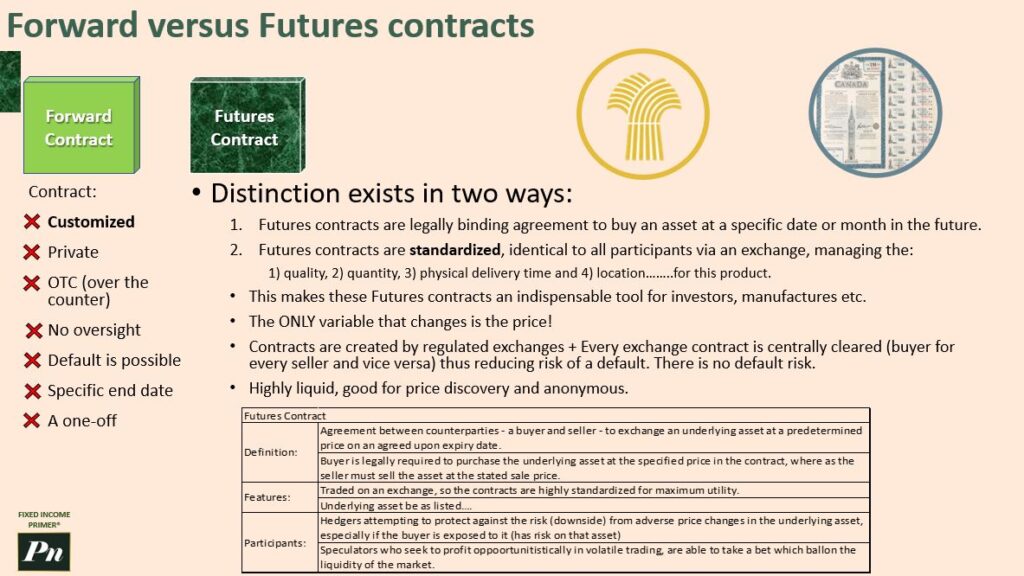

So now we’re going to talk about forward versus Futures contracts because we need to make now the distinction and just make sure that this is locked in your head and you get it. A forward contract is a unique contract, okay! It’s highly customized. It’s private. It’s over the counter or over the phone or over a dinner. You know, you can have the manufacturer of the flour and the baker get together and have lunch, and they would draft a legal document, a forward contract. The problem is there’s no oversight, and it’s possible that the baker could go out of business and not fulfill their obligation in terms of buying, giving the $70 to the flour maker, for example. In their example, we had before, there’s a specific end date, which is good, but it’s not so good in the sense that if you want to keep going with these contracts and it does end, and there’s no obligation to continue, and it’s a one-off agreement often. So forward contracts are quite narrow in their scope, and they are not exactly fit for purpose for the broader financial system. And one snag is that we talk about the forward price in a Futures contract. So don’t get those mixed up. This is a forward contract. Forward price is the price that is agreed to in the Futures contract.

Now I’m hoping by going back to this sort of textbook definition stuff, this will start to make more sense. Because we looked at some practical examples already, and now this is starting to kind of coalesce. There are two major distinctions between a futures contract compared to the forward contract. So these are the futures contracts, which are legally binding agreements to buy an asset at a specific date or month in the future. The month in the future concept will show that there’s actually a window in which you can deliver a set of bond futures, for example. Futures contracts are standardized, right?

I’m exiting out on the left all the things that are different here. Forward contracts are very, very customized. It’s identical to all futures contracts. All futures contracts are identical to our participants via an exchange, and they’re managing the quality, quantity, physical delivery time, and location of these products. And this makes this futures contract an indispensable tool because it’s so much more dynamic than just a one-to-one relationship between two counterparties, as with the forward contract. It’s kind of like when you get a student loan, you go to the bank and you have a loan, whereas a company issues new corporate debt, and then suddenly there’s this ecosystem that grows out of that where people buy and trade that company’s debt, independent of the company. It’s independent of the underlying company relationship. And you know, certainly people are trying to do that with student debt to try to create an ecosystem. But in reality, a futures contract creates an ecosystem in the same way. They have many participants taking positions, whereas a forward contract is really just two people, a dinner table agreement written in legal wording and contract obligations. Here we can have bushels of wheat that are standardized. We have sets of bonds that are standardized. The only variable that really changes in a futures contract is the price. That’s the big key differentiator. And contracts are created by the regulated exchanges, right?

We talked about the Dojuma Exchange, the Rice Exchange. We talked about the CME, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. Basically, at its core, there’s no default risk because every exchange contract is centrally cleared. There’s a buyer for every seller, and it’s automatic. If you have a short, then someone had to take a long by definition. There’s no question about that. But the key is, with the forward contract, the baker could go out of business and not fulfill their obligation to buy at seventy dollars for the bag of flour. But here, we’ve got the central exchange taking a critical function, and they add some additional sort of tools in their toolkit to protect themselves from this risk. But the default risk is not held by the participants. There is, however, risk in taking a position on the futures contract. The highly liquid nature of it is key too, so good for price discovery. It’s anonymous, right? You don’t have to know trader A, trader B, trader G, trader E, trader 10,000. And in fact, the more traders there are, the more indicative the above the nature of the underlying asset and the amount of energy around that asset at the time. And so, you’re getting some price discovery. You’re better understanding the underlying value of this asset at that point in time. And that spot time is when people are making financial decisions on where to allocate their capital and resources. So, it’s all part of this broader ecosystem of decision-making, really.

So, this is a classic textbook definition. On the bottom of the screen, this is the one that everyone starts out learning from. And I found that this was kind of annoying because if you don’t have the context, if you don’t have a broader sense of the examples that I’ve shown, I think it has helped, hopefully, with providing a little more color than the way that they’ve done it here, which is to list out all the different participants. We’ve got the hedgers and speculators. We’ve got traders, trades on exchange, underlying assets listed. You have all these assets listed. The key is the definition.

It’s like, okay, you walk away with a definition, but then it just seems like a sentence. Whereas I want to make it more tangible for myself and yourself to better understand this topic. So, futures, now I think it’s good to talk about philosophically. It’s kind of built on this long arc of progress as we’ve suggested, bending towards over time an ecosystem of better measuring value, of ways to better measure, quantify things. And as flawed as it is, it’s actually a reflection of human nature. And we, as humans, as you may have noticed, are kind of flawed. So, this system is an expression of an underlying thing, which is how our brains work and how finance is developed as a product of that. Just remember the story, right?

Futures and other financial ideas have fun origins stories

The forward contract was basically something that Thales of Miletus was using, the baker and the manufacturer, and it’s really about delivering, you know, pork bellies at a specific time on a specific date. And as we’ve said, futures are standardized. So, futures are really an expression of taking this forwards concept and really building on it. And I think it’s just worth taking a step back. A lot of the concepts in finance come from humble origins. They come from a simple place. For example, feudal lords in ancient times, we’re talking, you know, thousands of years ago, who had property passed down, probably through military victories being warlords or whatever. They had this property, and we can argue if that might be actually wrong that they had that property, and why do they have it? How do they get it? Is ill-gotten gains legitimate? Well, reality is uncomfortable. It sucks, and it’s just unfair. That’s the way the world is. These feudal lords have this property, and they lent it out to other people who can create value with that.

So, feudal lords would loan out land to shepherds, and shepherds would buy sheep and get sheep on that land. And so, borrowers had to provide some percentage of their flock of sheep back to the property owner at the end. And it might surprise you to learn that in Aramaic, the word for sheep sounds remarkably like what we use as the word for interest. The word “interest” comes from the ancient language Aramaic’s word for sheep. So, this whole concept of interest is actually just an expression of a pretty simple relationship. So, my point is really humble origins equal a modern system.

Another classic that I think I’ve already mentioned is the time value of money, right? If I have a hundred dollars today, then I can benefit from compounding interest. And if I look at the value of a hundred dollars in a year’s time, it degrades and discounts over time if I allocate it somewhere else. This discount team basically helps decision makers fully understand the costs and benefits of a specific decision and its future impacts. But what is it really about?

I’ll tell you, it’s actually about human nature. I want money now. All human beings want things now. They would prefer things in their position right now rather than at a future date. So you need to pay that person interest for giving you their money. They need to get some benefit for giving you their hundred dollar bill rather than them holding onto it themselves. It’s like, “I want an ice cream cone right now. I prefer it right now over in a year’s time.” So the whole financial mechanisms, all these things, actually come from humble origins or humble preferences. And we create sophisticated, quote-unquote, technology financial innovation or systems to really, when it boils down to it, express simple things, concepts into incrementally more complex financial technologies or solutions.

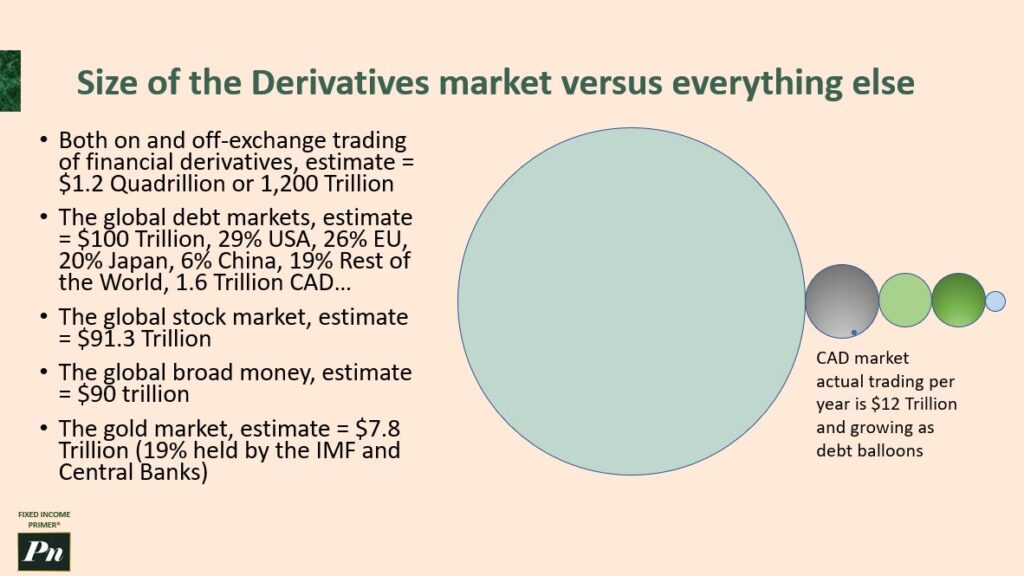

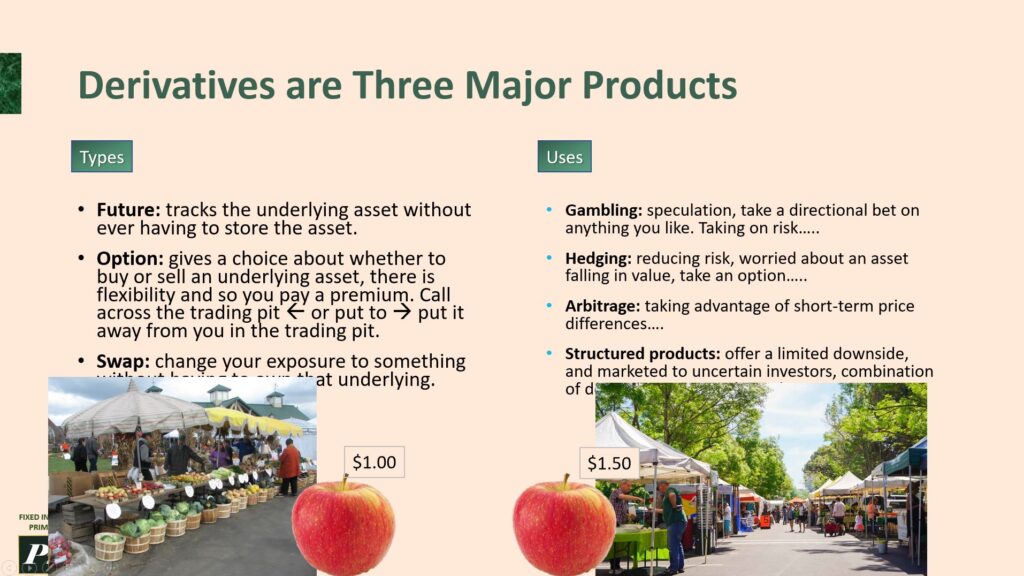

Derivatives are a huge part of finance