Origins of Multiculturalism: An Analysis of the Historical Emergence of the Canadian Multiculturalism Policy of 1971.

Official multiculturalism was a watershed in Canadian identity that originated as a consequence of the changes of the 1960s. In order to appreciate the historic shift towards multiculturalism policy, this article will achieve the following objectives. First, it will critique the political motivations and philosophical narrow-mindedness of the B&B Commission’s organizers. Second, this article will examine the Third Force’s[1] fight for recognition led by Senator Paul Yuzyk and other political activists. Thirdly, it will address the political controversy created by Prime Minister Trudeau’s 1971 House of Commons speech. Finally, the article will argue that despite the devotion of the Third Force advocates, multiculturalism policy had little to do with their efforts, concluding that this now fundamental policy for Canadian identity was actually a pragmatic and convenient compromise.

Official multiculturalism was a watershed in Canadian identity that originated as a consequence of the changes of the 1960s. In order to appreciate the historic shift towards multiculturalism policy, this article will achieve the following objectives. First, it will critique the political motivations and philosophical narrow-mindedness of the B&B Commission’s organizers. Second, this article will examine the Third Force’s[1] fight for recognition led by Senator Paul Yuzyk and other political activists. Thirdly, it will address the political controversy created by Prime Minister Trudeau’s 1971 House of Commons speech. Finally, the article will argue that despite the devotion of the Third Force advocates, multiculturalism policy had little to do with their efforts, concluding that this now fundamental policy for Canadian identity was actually a pragmatic and convenient compromise.

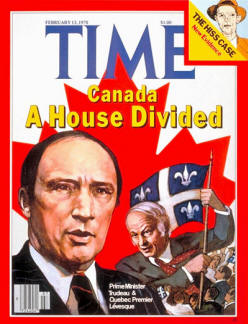

All of the relevant historical factors that led to Trudeau’s 1971 House of Commons speech materialized during the tumultuous period of the 1960s. In this period, no ethno-cultural group garnered more attention than the French-Canadians; understandable since Quebec’s ‘Quiet Revolution’ threatened to de-legitimize Canada. Quebec’s intellectual elite witnessed declining birth rates, increased urbanization and argued for a rejection of the second-class status of “the French Fact” in Canada.[2] By 1960, Jean Lesage’s Parti Liberal du Quebec committed itself to nation-building modernization, secularization and increasing Quebec’s autonomy under the campaign slogan “Maitres chez-nous”.[3] By rekindling the question “what does Quebec want?”, the Quiet Revolution triggered an identity crisis in Canada. Something had to be done. Changes in Quebec-Canada dynamics necessitated a response from federalist bureaucratic elite. [4]

Observing the discontent in his home province, Andre Laurendeau, then the editor of Le Devoir, proposed opening a commission on the status of French-Canadians to gain assurances of equality for both English and French at the federal level. [5] Agreeing with Laurendeau, the new Liberal Prime Minister, Lester B. Pearson, announced the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism in the summer of 1963 with Laurendeau as a co-chair along with A. Davidson Dunton. The first public consultation of its kind, the B&B Commission was the Federal government’s response to the sovereignist threat. Its central objective was to engage in a cross-country public tour to resolve the antagonism between the two founding nations of French and English Canada.

The B&B Commission was supposed to save Canada from the emerging discontent of the Quiet Revolution. The public consultation was touted as nothing short of epic, as the preliminary B&B report stated that “Canada, without being fully conscious of the fact, is passing through the greatest crisis in its history…it would appear from what is happening that the state of affairs established in 1867, and never seriously challenged, is now for the first time being rejected by the French Canadians of Quebec.”[6] Made explicit in its title, the Bilingual & Bicultural Commission’s goal was to reassert the dualistic ‘two solitudes’ philosophy of Canadian confederation. It was the proposed solution “to raise the state of the French language to parity with English, to make French a language of service to the public and of work in federal agencies”. [7] Obviously, failure to realize the goals set for B&B Commission would have symbolic and perhaps far-reaching political implications.

The B&B Commission was supposed to save Canada from the emerging discontent of the Quiet Revolution. The public consultation was touted as nothing short of epic, as the preliminary B&B report stated that “Canada, without being fully conscious of the fact, is passing through the greatest crisis in its history…it would appear from what is happening that the state of affairs established in 1867, and never seriously challenged, is now for the first time being rejected by the French Canadians of Quebec.”[6] Made explicit in its title, the Bilingual & Bicultural Commission’s goal was to reassert the dualistic ‘two solitudes’ philosophy of Canadian confederation. It was the proposed solution “to raise the state of the French language to parity with English, to make French a language of service to the public and of work in federal agencies”. [7] Obviously, failure to realize the goals set for B&B Commission would have symbolic and perhaps far-reaching political implications.

In assessing the documents from the period, the B&B Commission was actually quite dogmatic in this regard. It appears that the federalist strategy was to organize a public relations junket to convince Canadians of the wisdom of dualism. One classic example of this two solitudes vision is found in an interview – prior to launching the public consultation tour – where a CBC report asks if the Commission would deal with the concept of multiculturalism in which co-chair Laurendeau is seen shaking his head vigorously. Laurendeau then adds with confidence that “it’s a bicultural commission because the country is bicultural!”.[8] Unfortunately for Laurendeau, his philosophy would be further frustrated as the Commission commenced.

In hindsight, the B&B Commission could not help but evolve from its narrow conceptual framework into a Pandora’s box of challenges by other equality rights seeking groups. While the Commission welcomed public contributions to the debate, the Commission’s political elite relegated the contributions of other ethnic groups to the periphery: to merely “tak[e] into account the contribution made by other ethnic groups to the cultural enrichment of Canada”. [9] In response, these other ethnic groups argued that their language and culture was as vital to Canadian nation-building as the French-Canadians, particularly in Western Canada. [10]

Beyond the Quebec-Canada power struggle of the B&B Commission, diversity – synonymous with multiculturalism – was on the rise. This was partly because English-Canada’s immigration underwent a fundamental shift by the end of the 1950s with a surge in non-European immigration. Consequentially, a rights revolution was growing among a variety of disenfranchised minority groups.[11] The B&B Commission underestimated the reality that the Canadian identity crisis existed on more than the French-Canadian front:

“Over two hundred newspapers published in languages other than French and English, with fairly well defined Italian, Jewish, Slavic, and Chinese neighborhoods in large Canadian cities, and with visible rural concentration of Ukrainians, Doukhbors, Hutterits and Mennonites, how was it possible for a royal commission to speak of Canada as a bicultural country?[12]”

Today, multiculturalism is uncontested in its abstract philosophy of Canada. [13] At the time of the B&B Commission, however it was radical. All that was needed were political actors willing to challenge the assumed order of Canadian confederation. The political elite of Ukrainian-Canadian society was most adept at mobilizing interests shared by other ethnic groups collectively recognized as the ‘Third Force’.

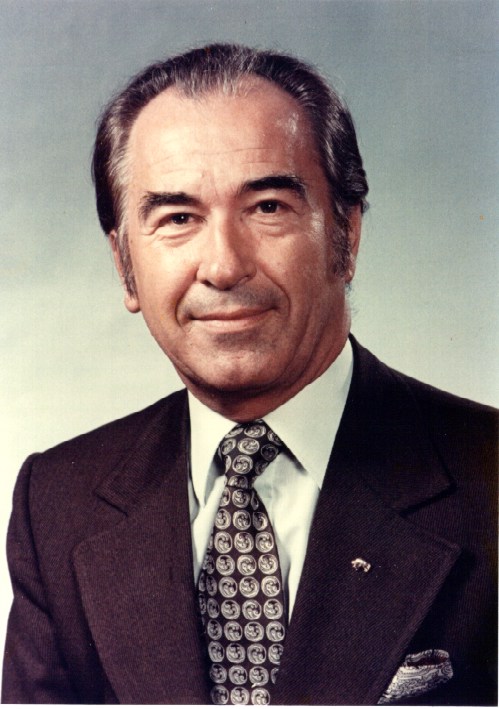

Their key spokesperson was a Progressive Conservative Senator from Manitoba named Paul Yuzyk. Appointed by John Diefenbaker on February 4th, 1963, Yuzyk was a Ukrainian-Canadian whose ethnic background did not coincide with the bicultural vision that was presented in the corridors of power. Citing his experience of inequality on the Canadian prairies – particularly when he was rejected as a Saskatchewan school teacher because of his ethnic-background[14] – Yuzyk argued against any form of ethnic discrimination. Senator Yuzyk’s advocacy of political change played a key role in mobilizing his fellow ethnics on the issue of integration, language and cultural protections including the Thinkers’ Conference on Cultural Rights in December, 1968. [15]

Their key spokesperson was a Progressive Conservative Senator from Manitoba named Paul Yuzyk. Appointed by John Diefenbaker on February 4th, 1963, Yuzyk was a Ukrainian-Canadian whose ethnic background did not coincide with the bicultural vision that was presented in the corridors of power. Citing his experience of inequality on the Canadian prairies – particularly when he was rejected as a Saskatchewan school teacher because of his ethnic-background[14] – Yuzyk argued against any form of ethnic discrimination. Senator Yuzyk’s advocacy of political change played a key role in mobilizing his fellow ethnics on the issue of integration, language and cultural protections including the Thinkers’ Conference on Cultural Rights in December, 1968. [15]

Senator Yuzyk’s seminal contribution to the narrative of multiculturalism was his ground-breaking maiden speech in the Senate on March 3rd, 1964. Entitled “Canada: A Multicultural Nation”, Yuzyk denied that Canada was ever bicultural and argued that the deux nations vision was not “the desired objective of our peoples”. [16] For Yuzyk and other followers, the Third Force had a cultural and political status equal to French-Canadian ethnicity “as co-builders of the West and other parts of Canada”. [17] Using empirical evidence, Yuzyk challenged the dualistic vision. For example, in the 1961 census, the non-English and non-French ethnic composition of the Canadian population was at 26% comprising a “numerical and proportional position [comparable] to the French Canadians”. [18] Interestingly, this speech also appealed to the rhetorical arguments that characterize multiculturalism today, stating that Canada would differentiate itself from the United States by being the unique “multicultural society of the world”. [19] The term multiculturalism was applied broadly as an alternative to biculturalism, with language constituting a primary role in ones culture. [20] This controversial maiden speech was well received in the Senate although his message was antagonistic to most of the dualistic discourse of the B&B Commission.

The most forceful confrontation with the dualistic mandarins of the B&B Commission occurred on December 7th, 1965. During these discussions, fellow Ukrainian-Canadian Manoly R. Lupul, along with several others, presented a brief advocating a ‘Third Force’ argument for Canada. On this day, Lupul advocated multilingualism and multiculturalism in at least the Western Canadian region in order to transmit the traditional Ukrainian-Canadian agenda: “the preservation and development of Ukrainian culture through as much language retention as possible”. [21]

The most forceful confrontation with the dualistic mandarins of the B&B Commission occurred on December 7th, 1965. During these discussions, fellow Ukrainian-Canadian Manoly R. Lupul, along with several others, presented a brief advocating a ‘Third Force’ argument for Canada. On this day, Lupul advocated multilingualism and multiculturalism in at least the Western Canadian region in order to transmit the traditional Ukrainian-Canadian agenda: “the preservation and development of Ukrainian culture through as much language retention as possible”. [21]

Lupul’s philosophy met with initially strong resistance from the Ottawa-based mandarins of the Commission. Lupul’s exchange with Pierre Trudeau at the B&B Commission exemplifies the desire to casually dismiss the ‘Third Force’ arguments. [22] Trudeau argued that Ukrainian-Canadians were destined to eventually assimilate into Canadian society anyway. Paradoxically, Trudeau argued that “the French, though ethnics, were not really ethnic”[23] essentially believing that the French-Canadians should not be destined for the same assimilationist fate as Ukrainians, deserving instead, a special status as a founding nation. [24] Trudeau’s harsh confrontation with Lupul exemplifies the fundamental disagreement on competing visions of Canada. Unfortunately resolving this philosophical conflict between these competing views of Canada’s federal framework would haunt Canada’s constitutional and historical development to this day.

As a consequence of these exchanges, the B&B Commission addressed the concerns of the Third Force in a fourth report released in mid-April 1970. Two years after the Commission’s most salient report, which formed the basis of the 1969 Official Languages Act, this report was much less significant. It appears that Book IV of the B&B Commission, The Cultural Contributions of Other Ethnic Groups satisfied no one completely but placated competing philosophical views with its vague platitudes about a multicultural Canada. Sixteen recommendations were advanced to encourage government sponsored recognition of other ethnic groups, it also recommended further research on diversity and calls for tolerance. [25] This was a substantial victory for multicultural advocates, however, the report was far from proclaiming a model based on the Third Force arguments of multilingualism and multiculturalism. With questionable sincerity, The B&B Commission invited “individuals to participate in a revival of ethnic subcultures”. [26] The B&B Commission still maintained the fundament duality of Canada “requiring members of all cultural groups to ‘choose between which culture they were to integrate”. [27] The Commission was philosophically schizophrenic in recognizing multiculturalism at all, however Canadian dualism would exist from coast to coast with the minor caveat that recognizing other groups was valid. In the fight for redefining Canadian identity, the Ottawa mandarins maintained their initial objectives since multiculturalism had few ramifications and was not taken seriously.

According to one Ottawa mandarin, Bernard Ostry, the deputy minister who drafted the original multiculturalism policy, “after its final volume reported that Canada was not bicultural but multicultural, Ottawa began to develop policies on multiculturalism (this was not the brain child of Pierre Trudeau and his Quebec lieutenants, as has been suggested)”. [28] The question remains, was it that the Third Force succeeded in their objectives or were there other factors at play?

According to one Ottawa mandarin, Bernard Ostry, the deputy minister who drafted the original multiculturalism policy, “after its final volume reported that Canada was not bicultural but multicultural, Ottawa began to develop policies on multiculturalism (this was not the brain child of Pierre Trudeau and his Quebec lieutenants, as has been suggested)”. [28] The question remains, was it that the Third Force succeeded in their objectives or were there other factors at play?

To recap, this article has thus far explained the central political objectives of the B&B Commission and chronicled key events in the mobilization of the Third Force which contested the Commission’s dualistic vision. It finally showed that recognition of the Third Force’s arguments was only partially addressed but not very seriously. This article will conclude with an analysis of the 1971 implementation showing that Third Force advocates had little do with the implementation of official multiculturalism since it was more likely a strategic compromise of pragmatic politics.

Official multiculturalism in 1971 was a watershed in Canadian history. The acceptance of this policy occurred in the House Commons on October 8th, of that year. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s speech entitled The Announcement of the Implementation of a Policy of Multiculturalism within a Bilingual Framework argued that “there cannot be one cultural policy for Canadians of British or French origins, another for the originals, and yet a third for all other. For although there are two official languages, there is not official culture”[29]. Curiously, on that fateful day, the tripartisan reaction was resoundingly supportive. Robert Stanfield re-emphasized the dualist nature of Canada but agreed with Trudeau, David Lewis was also supportive and, even Réal Caoutte was in agreement despite contradictions in his argument[30]. In reading the House of Commons debates, it seems possible that given the theoretical nature of the policy, none of the political leaders were able to quantify its political meaning[31] or see an electoral advantage in denouncing multiculturalism.

On the one hand, it arguably added another twist to Canada’s identity crisis by “superimpos[ing] a one Canada perspective over the prevailing deux nations view”[32]. On the other, it can be argued that the Prime Minister did not seriously support the policy in concrete terms. There is no documentation of Trudeau ever speaking or writing publicly about multiculturalism after this speech and lackluster policy implementation is evident[33]. In fact, Trudeau’s advocacy of multiculturalism contradicted his exchange with Lupul nearly six years earlier over multilingualism and multiculturalism in Canada. A study of his political philosophy would also attest to the fact that Trudeau could, at best, only partly support this policy of government sponsored cultural pluralism. It is then possible that while multiculturalism is publicly viewed as major aspect of Canadian identity today, Trudeau’s multiculturalism may not have been intended to be serious at all. Book IV of the B&B Commission could have easily been ignored, it is far more likely that multiculturalism was a strategic compromise.

The reasoning behind Trudeau’s multiculturalism is elusive. Various academics, journalists and politicians have developed hypotheses for why this enigmatic policy occurred in Canadian history. Most argue that the October 8th speech was some variety of convenient and strategic compromise. Some have argued that the Liberal government was simply making an opportunistic electoral calculation, attempting to strengthen ties in immigrant communities which had been a stronghold for Liberal party electoral success in the past. Richard Gwyn believes this was the case, accusing Trudeau of simply creating a program “that functioned as a slush fund to buy ethnic votes.”[34]

Other academics such as Carl Peter and Wsevolod Isajiw argue that multiculturalism was a subterfuge for denying any cultural hierarchy between the dominant English and the subordinate French culture in Canada[35]. René Lévesque famously scoffed that “multiculturalism, really, is folklore…It is a red herring. The notion was devised to obscure the Quebec business, to give an impression that we are all ethnics and do not have to worry about special status for Quebec.”[36] A complex political debate in the academic community has occurred over this idea that Trudeau was attempting to prevent full dualism of language and culture which may have arguably strengthened Quebec separatism by affirming its territorial legitimacy. [37] Even Quebec federalists such as Premier Robert Bourassa argued it was contradictory to have a policy of bilingualism along with multiculturalism.[38] According to Isajiw, multiculturalism was merely a pragmatic attempt to deal with the irreconcilable challenges of a divided federalist state.[39] It was a compromise because no one was completely satisfied, minority groups had to settle for bilingualism over multilingualism while Quebecois had to settle for multiculturalism over biculturalism.

Other academics such as Carl Peter and Wsevolod Isajiw argue that multiculturalism was a subterfuge for denying any cultural hierarchy between the dominant English and the subordinate French culture in Canada[35]. René Lévesque famously scoffed that “multiculturalism, really, is folklore…It is a red herring. The notion was devised to obscure the Quebec business, to give an impression that we are all ethnics and do not have to worry about special status for Quebec.”[36] A complex political debate in the academic community has occurred over this idea that Trudeau was attempting to prevent full dualism of language and culture which may have arguably strengthened Quebec separatism by affirming its territorial legitimacy. [37] Even Quebec federalists such as Premier Robert Bourassa argued it was contradictory to have a policy of bilingualism along with multiculturalism.[38] According to Isajiw, multiculturalism was merely a pragmatic attempt to deal with the irreconcilable challenges of a divided federalist state.[39] It was a compromise because no one was completely satisfied, minority groups had to settle for bilingualism over multilingualism while Quebecois had to settle for multiculturalism over biculturalism.

As this article suggested, the mobilization of the Third Force to contest the B&B Commission contributed to the creation of official multiculturalism policy. However, given the evident strategic compromises undertaken in its creation, it is unlikely that Yuzyk’s speech, Lupul’s advocacy or the Third Force claims were the chief factors in attitudinal change on the part of Pierre Eliot Trudeau. Among some academics and exemplified in Ukrainian-Canadian newspaper around the time of Yuzyk’s death, Yuzyk was declared the ‘Father of Multiculturalism’. [40] However, history shows that although Yuzyk may have been a primary spokesperson, his contribution is evidently limited by the broader political reality that threatened the very existence of Canadian confederation. The fact that Paul Yuzyk is not a household name may also suggest that historians have overlooked his contributions for the above reasons. Multiculturalism was more a pawn in a strategic game to placate Quebec nationalism while advancing the Liberal Party’s electoral prospects, two ideas that are often associated together.

Most of the key factors that led to multiculturalism originated in political and cultural upheaval of the 1960s. Despite the questionable nature in which the policy was enacted, Canadians have benefited greatly as a result of multiculturalism. Some historians suggest that the logical progression to a multicultural policy began long before the 1960s, in truth this competing vision of Canada that contrasted dualism had been growing since the beginning of confederation. Multiculturalism could be said to be inevitable since it followed the traditions of John Murray Gibbon’s Canadian Mosaic to its rational conclusion. Ultimately, however, this article has argued that multiculturalism was a convenient compromise that came about largely because of the political advantages of its implementation. Such is the harsh historical reality of our mythologized identity.

Most of the key factors that led to multiculturalism originated in political and cultural upheaval of the 1960s. Despite the questionable nature in which the policy was enacted, Canadians have benefited greatly as a result of multiculturalism. Some historians suggest that the logical progression to a multicultural policy began long before the 1960s, in truth this competing vision of Canada that contrasted dualism had been growing since the beginning of confederation. Multiculturalism could be said to be inevitable since it followed the traditions of John Murray Gibbon’s Canadian Mosaic to its rational conclusion. Ultimately, however, this article has argued that multiculturalism was a convenient compromise that came about largely because of the political advantages of its implementation. Such is the harsh historical reality of our mythologized identity.

Work Cited

Bissoondath, Neil. Selling Illusions: The Cult of Multiculturalism in Canada. Penguin Books Canada Ltd: Toronto, 2002.

Bociurkiw, Michael. B. Deputy Prime Minister, hundreds attend Ottawa funeral. The Ukrainian Weekly, Sunday July 20th, 1986.

Book IV of the B&B Commission: The Cultural Contributions of Other Ethnic Groups, 1970.

Bourassa, Robert. “Objections to Multiculturalism,” letter to Prime Minister Trudeau, Le Devoir, November 17, 1971.

Breton, E. Canadian Federalism, Multiculturalism and the Twenty-First Century. International Journal of Canadian Studies, 21, Spring, 160-75.

CBC Canada: Achieves: The Road to Bilingualism. http:///archives.cbc.ca/IDC-1-73-655-3624/politics_economy/bilingualism/clip1, viewed: March 2nd, 2007.

Esman, J Milton. The Politics of Official Bilingualism in Canada. Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 97, No. 2. (Summer, 1982), pp. 233-253.

Fleras, Augie & Elliott, Jean Leonard. Engaging Diversity: Multiculturalism in Canada. 2nd Edition. Nelson: Thomson Learning: Toronto, 2002.

Gwyn, Richard. The Northern Magus. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1976.

Gibbons, J. Canadian Mosaic: The Making of a Northern Nation. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1938.

Harney, Robert. “So Great a Heritage as Ours” Immigration and the Survival of the

Canadian Polity….Daedalus; Fall 1988; 117, 4. pg. 51.

Isajiw, Wsevolod. Understanding Diversity. Thompson Educational Publishing: Toronto, 1999.

Kymlicka, Will. Finding Our Way: Rethinking Ethnocultural Relations in Canada. Oxford: University Press: 2004. Levesque, Rene. Quoted in Colombo, The Dictionary of Canadian Quotations.

Lupul, Manoly R. The Politics of Multiculturalism: A Ukrainian-Canadian Memoir. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press: Toronto, 2005.

McRoberts, Kenneth. Canada and the Multinational State. Canadian Journal of Political Science. Citizenship and National Identity (Dec., 2001), pp. 683-713. Vol, 34.

Ostry, Bernard. Digging up identity issues. Canada’s ethnic makeup is branching out in new directions. Shouldn’t we think about this before it’s too late? The Globe and Mail: Toronto, Ont.: Nov 15, 2005. p. A27.

Palmer, Howard ed. Immigration and the Rise of Multiculturalism. Copp Clark Publishing: Toronto, 1975.

Peter, Carl. The Myth of Multiculturalism and Other Political Fables, pp. 56-67. P.E. Trudeau, Robert Stanfield, David Lewis and Real Caouette, Federal Multicultural Policy: House of Commons Debates, October 8, 1971, pp. 8545-8.

Wilson, Seymour. The Tapestry Vision of Canadian Multiculturalism. Canadian Jounral of Political Science, Vol. 26, No. 4. (December, 1993), pp. 645-669.

Yuzyk, Paul (Senator). For A Better Canada. Ukrainian Echo, Publishing Co. Ltd: Toronto, 1973.

[1] The Third Force refers to Canadian immigrant communities considered non-English or non-French in cultural orgin.

[2] Harney, Robert. “So Great a Heritage as Ours” Immigration and the Survival of the

Canadian Polity….Daedalus; Fall 1988; 117, 4. pg. 54.

[3] Esman, J. Milton. The Politics of Official Bilingualism in Canada. Political Science

Quarterly, Vol. 97, No. 2. (Summer, 1982), pp. 244.

[4] Alternatively referred as the Ottawa Mandarins.

[5] Palmer, Howard ed. Immigration and the Rise of Multiculturalism. Copp Clark

Publishing: Toronto, 1975, pp. 115.

[6] Royal Commission preliminary report, released: July, 1965.

[7] Esman, J Milton. The Politics of Official Bilingualism in Canada. Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 97, No. 2. (Summer, 1982), pp. 233.

[8] CBC Video: Archives. (http:///archives.cbc.ca/IDC-1-73-655-3624/politics_economy/bilingualism/clip1)

[9] Palmer, 115.

[10] Wilson, 1993.

[11] Fleras, Augie & Elliott, Jean Leonard. Engaging Diversity: Multiculturalism in Canada.

2nd Edition. Nelson: Thomson Learning: Toronto, 2002, 62.

[12] Palmer, 115.

[13] Multiculturalism has a disputed meaning. This article will argue that it was widely praised precisely because the term is amorphous.

[14] Yuzyk, Paul (Senator). For A Better Canada. Ukrainian Echo, Publishing Co. Ltd: Toronto, 1973, pp. 10.

[15] Yuzyk, 13.

[16] Ibid, 35.

[17] Ibid, 30.

[18] Ibid, 26.

[19] Ibid, 38.

[20] Yuzyk saw linguistic dualism of English-French, English-Ukrainian etc.

[21] Ibid, 57.

[22] Ibid, 54.

[23] Ibid, 54.

[24] Ibid, 54.

[25] Book IV The Cultural Contributions of Other Ethnic Groups of the B&B Commission, 1970.

[26] Ibid, 113.

[27] Lupul, 112.

[28] Ostry, Bernard. Digging up identity issues. Canada’s ethnic makeup is branching out in

new directions. Shouldn’t we think about this before it’s too late? The Globe and Mail: Toronto, Ont.: Nov 15, 2005. p. A27.

[29] P.E. Trudeau, Robert Stanfield, David Lewis and Real Caouette, Federal Multicultural Policy: House of Commons Debates, October 8, 1971, pp. 8546.

[30] October 8th, 1971 Debates, pp. 8545-8.

[31] Defining multiculturalism in precise terms is an intellectually taxing challenge given the variety of interpretations forwarded by the public, politicians and historians alike and could easily be the subject of another article on the evolutionary history of multiculturalism policy post-1971.

[32] Fleras & Elliott, 54.

[33] Kymlicka, 145.

[34] Gwyn, Richard. The Northern Magus, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1976.

[35] Peters, Carl. The Myth of Multiculturalism and Other Political Fables, pp. 56-67.

[36] Levesque, Rene. Quoted in Colombo, The Dictionary of Canadian Quoations.

[37] Jerome Black, Political Science 411 Lecture November 15th, 2006.

[38] Bourassa, Robert. “Objections to Multiculturalism,” letter to Prime Minister Trudeau, Le Devoir, November 17, 1971.

[39] Isajiw, Understanding Diversity (Toronto: Thompson Educational Publishing, 1999, Chapters, 1, 8, pp. 34.

[40] Bociurkiw, Michael. B. Deputy Prime Minister, hundreds attend Ottawa funeral. The Ukrainian Weekly, Sunday July 20th, 1986.