Chapter 1 | Benjamin Franklin and the Invention Of America

Chapter 1 | Benjamin Franklin and the Invention Of America

Benjamin Franklins’ life is an interesting one, and the first chapter explores the depths of his character in the outset of that life. Significant emphasis is placed on the fact that Franklin’s was not a linear but rather a multi-layered character, who carried facets from his different experiences in life, all in a single, complex yet amusing entity.

Basically, Benjamin Franklin was a polymath.

Benjamin Franklin is introduced keeping in context with his autobiographical work, as a cheeky young man with the guise for humility, arriving in Philadelphia to develop his own personality. As the story progresses, the tone changes to that of an old man, writing his life’s story in retrospection and with the aim of passing it down to posterity. Therefore, this work spans a full circle where you will come to know the person of Benjamin Franklin rather intimately.

Benjamin Franklin’s character is a rather endearing one- despite being a statesman; he was approachable, accessible and even relatable. Benjamin Franklin adopts a conversational and witty tone to write his autobiography, which helps you to see him not as someone on a pedestal but as someone from among the masses, contemporary even.

Apart from his admirable personality, Benjamin Franklin was also a man well versed in the arts and sciences. An intellectual man, we will see that he turns out to be a successful scientist and innovator with some important inventions to his name. He also had proficiency in the language, writing, and management- skills he honed to become an efficient diplomat, writer, and business strategist. His intellectual inclinations made him a philosopher; a pragmatic one at that.

Franklin came from the American middle class and despite his ascent in the world, he did not forget his roots. This gives an earthiness to his humour that comes through in his writing; writing that appeals to the masses. His belief in the power of the middle class as the force that will drive a new nation to prosperity reflects in his policies and the many measures he took to empower them. He prized civil harmony and undertook several civic- improvement programmes as he sought to give more power to the people who formed the essence of a democracy.

This work is a careful study of Franklin’s character that also turns out to a study in the changing paradigms of American society itself. He has admirers as well as critics, based on the time context he is viewed in. Some praise his materialistic approach to life while others decry his lack of vision for an exalted existence. The romantics vilify him while the entrepreneurs glorify him. This book, however, insists that lessons that are to be drawn from Benjamin Franklin’s life are far more complex than this binary. When reading this book, try to engage with Franklin’s character with a clean slate and not view his motivations that translated into actions as the maxims he swore by in life, because people are definitely more complex than that.

Chapter 2 | Pilgrim’s Progress

Chapter 2 | Pilgrim’s Progress

The opening of the second chapter familiarises us with Benjamin Franklin’s lineage. The aim of this approach is to educate a biographer about a personality by examining his family history. We come up close and personal with the character of Benjamin Franklin’s great-grandfather, grandfather and father, all of who possessed a strain of dissent and intellectual proficiency, which trickled down to his generation.

A rather descriptive account of the family tree informs us that his family had always lived in Ecton, Northampshire, and operated the smith’s business. Further elucidation details his father’s brothers’ lives and their peculiar qualities. From this section, we also find that the Franklin’s family practiced Protestantism in a time and land when it was looked down upon and even persecuted.

Considerable space has been dedicated to the character of Josiah Franklin, Benjamin Franklin’s father, perhaps as a result of the profound impact that he had on the latter’s life. An original piece from the autobiographical manuscript has been included in the book where Franklin talks at length about the inspiring spirit of his father’s character. A critical analysis at this point reveals that the idealistic description may be motivated by a desire to evoke respect from his son for his grandfather, to whom this account is addressed.

The rest of the chapter focuses on Benjamin Franklin’s childhood. His inquisitive and inventive streak was apparent even in his early years. Another trait that would become dominant later on in his life, that of leadership and organisational abilities, was also conspicuous even in his fun and games. He continues recounting his early years from the time Benjamin joined his father’s business. Since his heart was not in it, he could not sustain interest. However, his inquisitiveness made sure that he had a valuable take-away even from a task he found drab.

Further, we also come to know about Franklin’s other great interest, reading. He indulged in a variety of books, which is exemplary of the author’s voracious appetite for knowledge. The Netflix of the 18th century was in these books which had great influence on him, and he acquired many skills because of them.

Owing to his penchant for reading, his father sought to set him up in a printing press. He was employed in his brother’s press at twelve; to work as an apprentice. He also developed a knack for prose during this period. His new interest soon translated into an interest in debate and argumentation. To nurture it, he would spar with a friend of similar temperament, John Collins. Despite the clarity of thought, Franklin fell short in arguing his side, for want of better writing skills. His father helped him hone his skills by pointing out his mistakes. He then adopted a sophisticated method of memorising words and ideas that he would like to use in his writing. His moment of validation came when he wrote an opinion piece for his brother’s paper, and it found great acclaim among the latter’s friends who contributed to the paper.

Now, we come to know that this was a time when political correctness was observed rather strictly, and its violation could make one liable for punishment. Kind of like 21st century North America! Something similar happened with Benjamin’s brother, who was imprisoned for running a piece in his paper The New-England Courant that was unacceptable to the Assembly, the governing authority. Benjamin decided to write with the pseudonym Silence Dogood a middle aged widow; when Benjamin’s brother learned about the ruse; James was upset. Following this incident, Benjamin had to take over the printing press. However, this carved a new rift between the brothers, which only deepened with their clash of ideas, and attitudes. Therefore, the story will now take you on a journey with Benjamin Franklin as he parts ways with his to find with own; he left his job without telling anybody.

Chapter 3 | Journeyman

Chapter 3 | Journeyman

Benjamin Franklin appreciated rationality, as a virtue greatly. He was both an ardent practitioner in his life as well an observer of rationality in others life. You will find frequent examples drawn of this characteristic of his from his early apprenticeship days.

Franklin was a practicing vegetarian, as he saw the futility in the expenditure of time and money dedicated to lavish food. However, on his trip to New York, when he could rationalise eating fish to himself by reasoning that if they can eat each other, why should not he indulge himself. Franklin’s adroitness at rationality made him an important figure of the European Enlightenment when the virtue was hailed. We find that man’s ability to rationalise what he finds convenient, was of specific fascination to Franklin.

Continuing from the last chapter, we find ourselves back at Franklin’s runaway journey when his friend, John Collins arranged for him to board a ship to New York so that he would start a new life there. He met the sole printer there, but he sent him off to Philadelphia to work for his son. When he could not find work there either, he was introduced to his employer-to-be, Samuel Keimer. He was just seventeen years old at this time. Therefore, you can comprehend that Benjamin Franklin was a man of strong mind and heart, who was ready to brave unexplored territory in order to carve a niche for him.

He developed a good rapport with Keimer as they both found common interest in Socratic argumentation. Benjamin’s magnetic persona also helped him win friends in a new place, people who were of a similar temperament and taught him lessons that he carried with him for life.

Franklin’s writing skills, which he had been honing seriously, found wide acclaim by accident and a worthwhile patron in Governor Keith. However, his promises turned out to be empty, and Franklin learned about the folly of blind faith. From the trajectory of a few friendships and relationships that Franklin formed in these years and which fell apart for one reason or another, it can be concluded that Franklin’s charm could easily attract friends, patrons, and admirers, but keeping them was an art he still had to master.

During his time as a printer, Franklin indulged his philosophical interest and wrote a dissertation concerning free will and the idea of God. This early work of his was a rather shoddy attempt at philosophical writing. However, his position can be defended by the immaturity of his years. Through this writing attempt, it becomes clear that he was not a religious bigot and in fact was pen to scrutinising all elements of religion. He opted for a brand of religion that was pragmatic and where the pursuit of salvation was achieved through good deeds.

Franklin’s obsession with rationality and leading a meaningful life urged him to write a ‘Plan for Future Conduct’ to guide his endeavours. This lists of pragmatic rules sought to make him more of a likeable and productive person in life.

On his voyage back to America from London, he made keen observations about human behaviour that instilled in him a greater appreciation for society. He also honed his scientific acumen in this period and armed with his pragmatic rules for a successful life, Benjamin Franklin was ready to set up a new life in America.

Chapter 4 | Printer

In the fourth chapter, we delve deeper into Benjamin Franklin’s character. In the vast repository of talents he possessed, a flair for salesmanship is also featured. However, when life threw a curveball at him, and he could not make much of it, he fell back on what he knew best, the print business.

Franklin had honed his talents so much as to become indispensable for people around him. For instance, we are told that his employer, Keimer had to beg him to return after the previous fallout because only he could produce the finesse Keimer’s work demanded. Inevitably, his talents could not be tamed for long, and he set out again to make his own niche by opening up a print shop.

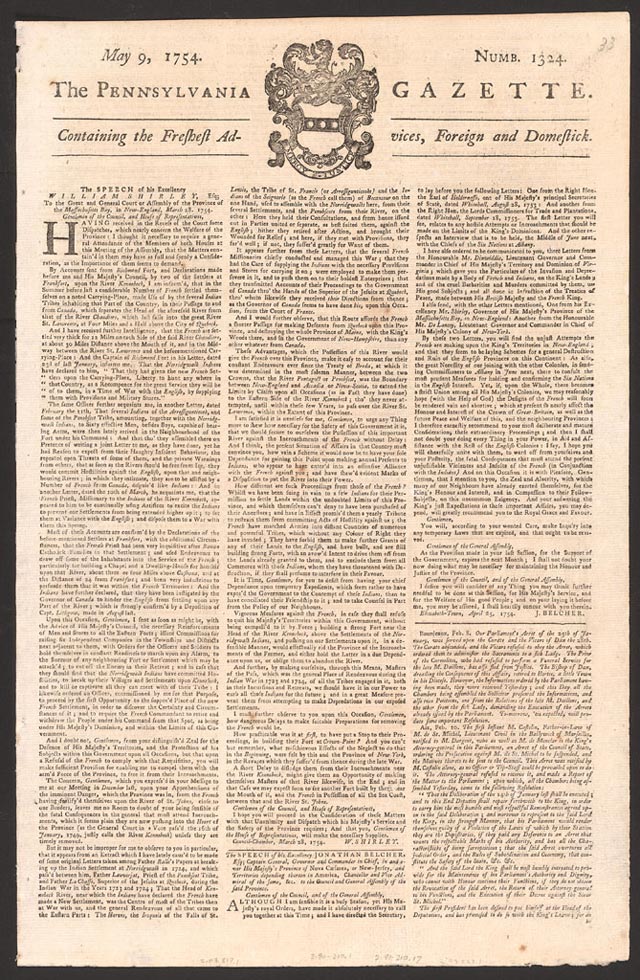

Franklin carefully created an image for himself and his business The Pennsylvania Gazette. He did not consider it merely as a career. Rather, it became a way of life for him. Despite reaching the pinnacle of his career as the President, he continued to identify himself as a printer. This goes on to display the dedication and respect he developed for his work.

After going through all the chapters till now, we can confidently say that Franklin was an intellectually inclined man who constructed opportunities to indulge his love for debate and thinking. An important outcome of this was the Junto / The Leather Apron Club, a group of talented young men whom Franklin employed to encourage his cause. His conversational style can be analyzed as disarming, engaging and effective, which helped him carve a successful public persona for himself as a man of intellect.

Early beginnings of Franklin’s interest in civic life can be observed at this stage itself as he used the platform of the Junto not only to discuss but also promote plans for civic development. Therefore, this can be identified as the nascent stage of Franklin’s journey as a celebrated statesman.

Franklin undertook ventures like the Busy Body Essays and Pennsylvania Gazette, through which he established credibility for his career as a publicist. Having risen in his public life, he then directed towards his attention towards private life. Many prospects fell through, mainly for want of suitable dowry until Franklin “chanced” upon Deborah Read. She did not come with a dowry, but as Franklin would later realize, made a better partner for him with her frugality and practicality.

Benjamin’s personal life, much like his public one, was not devoid of scandal, the most uproarious one being his allegedly illegitimate son, William. Even though his descent is a matter of vibrant debate to this day, Franklin never denied his paternity.

From instances of his writing, we can read that Franklin had formulated a concrete idea of what a perfect woman should be like: frugal and industrious. This notion was a dominant theme in his works, which can be seen as sexist from a modern lens. However, despite his primitive ideas about women, he did not limit his advice to only them. He called out men too, on their extravagance and wasteful ways. Therefore, we can conclude that he had struck an unusual balance between primitive and modern ideas in his writings…arguably.

Lucky for Benjamin, Deborah turned out to be an embodiment of traits he deemed virtuous for a wife. Therefore, they formed a companionship where Deborah became his partner both in the household and at work. From a detailed account of the personal dynamic between the duo, it can be inferred that despite some of his rather bigoted views extolling docility, obedience, and servitude for married women, he did appreciate the rebellious and assertive nature of his wife. Theirs’ was not a love that manifested overtly in grand gestures but can be found in subtle ones, like in the letters that Franklin wrote to his wife which are mentioned in the chapter.

Almost as if out of force of habit, Franklin outgrew Deborah. He had developed a character trait of not following through with relationships and followed suit in this marriage. Their personalities and interests came to contradict each others’, and Franklin stayed away from her for a major part of their marriage.

Apart from his marriage, another relationship that would have a profound impact on Benjamin was with his son, Francis. Adorably called Franky, Franklin doted on him and was proud of how curious he was. However, as we see, this turned into a bitter memory for him as he passed away at the tender age of four from smallpox. This made Benjamin a life- long advocate of inoculation and also translated into poignant works that he wrote in his memory.

Moving on, we return to the theme of spirituality in Franklin’s life. At this stage in his life, Franklin seems to have held his views against the wastefulness and dogmatism of organized religion. He continued to be tolerant of other faiths and sects. Benjamin’s brand of religion, as he mentioned in his writings, preached the importance of closeness with God but with pragmatism and devoid of dogma. The developing clarity of his ideas can be gauged by the superior quality of his later work, titled ‘Articles of Belief and Acts of Religion,’ when compared with his earliest attempt of ‘Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity.’

Benjamin Franklin had made it a mission in life to lead it as virtuously as humanly possible. In fact, he made a mechanical process out of this by making himself a list of virtues to abide by. A scrutiny of this list reveals that it was made rather conveniently to help him succeed in life by keeping his efforts on the right track but not chastising him too much. Therefore, it was not constructed with an abstract aim, such as that of spiritual salvation but a more fathomable, practical one.

Benjamin’s religious ideas would attract admirers and critics alike and result in the outstanding success of his Poor Richard series. He became an American icon of the Enlightenment movement of Europe as he worshiped all notions that the movement promulgated: reason, logic, and tolerance as opposed to dogmatism and bigotry.

In conclusion, it can be inferred that by this time, Benjamin had formulated a solid religious identity that was very different from those prevalent in his times. He used his wit, charm, and audacity to promote these ideas through his writings, following the Junto principle of revealing personal ideas through indirection.

Chapter 5 | Public Citizen

By this chapter, we have learned that Benjamin Franklin’s religious ideas were inclined towards pragmatism, tolerance, and appreciation of a civic sense in man because he equated ‘goodness with godliness.’ An extension of this idea can be seen in the manifestation of several organizations for the public good that operated under Benjamin’s watch.

These institutions- hospitals, libraries, fire brigades, were built and supported by an American community that extolled the values of individualism and communitarianism in the same breath. The existence of this paradox was enabled by Franklin’s fervent reinforcement of the idea that a keen civic sense is necessary for the development of the individual as well as the community he was part of.

During the wave of Great Awakening, Franklin encountered a number of personalities that preached strains of faith different from him, similar as him or those that simply amused him. We see that by defending or admonishing them, Franklin wove together his financial interests with his personal zeal for civic pursuits.

As Franklin continued expressing his dissident views through his newspaper, it gained popularity for its anti-establishment and rational sentiment. However, he competed with another prominent newspaper of the time, American Weekly Mercury run by Andrew Bradford. The recollection of sparks between them reveals that Franklin was a prudent businessman who chose his battles wisely and even worked in tandem with rivals when it benefitted him.

Further, as we look into the development of Franklin’s character, we come to evaluate his views about women. Even though not as sexist as the gentry in his day and maybe to an extent modern, Franklin still reared some regressive ideas about the education of women. This dichotomy is exemplified in the case of his daughter Sally, for whom he arranged a proper education in academic subjects, but the emphasis was always laid upon practical subjects that would make her an agreeable homemaker.

Writing to his friends and prospective suitors about his daughters, he would exalt her capacities as a smart and industrious person, but with an undertone that appreciated the usefulness of these traits in making her a good housewife. The duality in his attitude towards woman also comes forth in his writings. On the one hand, he writes the extremely sexist, almost degrading piece about why older women make better mistresses than young ones and on the other hand, pens the ‘Speech of Polly Baker’, which is an excellent critique of the hypocrisy of society towards a woman’s sexual liberty.

Franklin continued his mission of spreading pragmatic knowledge and power of reason among people by the establishment of organizations like the American Philosophical Society and the more radical Pennsylvania Militia. The success of these institutions reinforced in him the belief that a union of people with common interests was capable of ruling itself and creating a productive society.

This realization and his success in a social and professional capacity would prompt him to retire from the printing business and focus on the other callings in his life; his love for science and penchant for politics.

Chapter 6 | Scientist and Inventor

Benjamin Franklin’s most well-known achievements apart from the field of politics are in science. As we have noted earlier, he had inherited inquisitiveness and nurtured it with voracious reading and meaningful inquiry whenever possible. That enabled him in making significant scientific innovations from as early as in his 20s. His retirement from the printing business afforded him the luxury of time to pursue his curiosities.

Since a young age, Franklin had been experimental and had tried to employ new- found information in everyday tasks to produce something new. The kite and key experiment that catapulted his name into the ranks of Newton and Watson and Cricks was a result of this very enthusiasm to see science in action.

Interestingly, despite being a shrewd businessman, Franklin pursued science purely for pleasure. We come to this conclusion from the evidence that he declined patents and did not necessarily seek utility in his experiments as long as they were able to amuse him.

Practical use of the procedures, even though a secondary goal, did feature as a requisite in his experiments and led to the development of a new design of a stove that produced lesser smoke. The first catheter in America was also a product of this habit.

A detailed study of the process that led to the famous ‘lightning is electricity’ experiment reveals the meticulous method that Franklin observed; relentless endeavor, curiosity, improvisation and keen observation. Despite this, his lack of interest in scientific laws and limitation of his sphere of interest to experimentation leads us to the conclusion that he was not a systematic scientist but more of a whimsical experimenter.

His scientific progress drew equal amounts of applause and admonition. On the one hand, the religious community condemned his innovations as ‘ungodly’; on the other hand, the scientific community went gaga over him and showered him with honorary doctorates. This dichotomy was settled in the succeeding generations when the scientific worth of his work was unanimously established.

Benjamin Franklin’s lack of a formal education in theoretical mathematics or physics can be pegged as the reason why he cannot be considered a scientist of the same merit as Galileo or Newton. However, when we weigh the theoretical importance of his seminal works, we can establish unequivocally that his findings formed the bedrock of some the most basic scientific principles that were later sophisticated by scientists and put to practical use. A prominent example of this can be his discovery of the absorptive nature of black and white color.

We can, therefore, conclude that Franklin was a stellar example of the Age of Enlightenment. He possessed a robust curiosity and the will to experiment to quench his curiosity. He proved to the world that ‘philosophical amusements,’ as scientific experiments if pursued with vigor, have the capability of putting a man in control of even nature’s agents. This notion reinforced the idea of belief in man’s inherent intellectual ability, which was the basic theme of the Age of Enlightenment.

Chapter 7 | Politician

In this chapter, we explore the characteristics that helped Benjamin Franklin become one of the most successful political leaders to have graced our past. First off, we discuss the humanitarian sentiment that he nurtured, and that drew him to the public service sphere.

Franklin believed that a successful civic society is possible only with the active participation of its citizens. He also laid emphasis on the values of pragmatism and tolerance in conducting state affairs. That was the driving principle behind his effort for a non- sectarian educational institution (which resulted in the present day University of Pennsylvania) and a public and private funded hospital.

Benjamin’s ingenuity gave birth to the matching grant, a system of joint government and private funding that is prevalent in America to this day. Although not a libertarian in the present sense of the term, he did believe in the limited control of the government in civic affairs.

Additionally, he favored a government that would strike a right balance between public and private collaborations to produce maximum benefit for the people. However, his beliefs were not binary. Through letters that he sent to friends discussing his political philosophy, we find that he was skeptical of going overboard with public welfare, lest it should lead to complacency and laziness among masses.

However, these were more of questions than assertions. The composition of his political philosophy can be broken down into some basic elements: resistance to establishment, tolerance and non- sectarianism, freedom of social mobility and exaltation of the middle class as the savior of society. He believed in an egalitarian and democratic governance, which was also inclusive of new talent and not just a select elite.

He cannot be called a conservative really, but his ideas were not entirely free of the prevalent currents of thought. For instance, his stance against slavery was not based on the immorality of the act but its economic impracticality. However, he was soon to re-evaluate his position and become a fervent abolitionist.

Benjamin began a formal political career by being elected to the Philadelphia Assembly. He continued his public welfare schemes after assuming office. Federalism, as a system of governance, also saw the light of day under his leadership at the Albany conference. He actively began nurturing his non-parochial view for the American society, where the colonies could unite into a nation.

A look into the amorous relations that Franklin forged out of his marriage was always short of overt passion and often tinged with a paternalistic attitude that he adopted towards the paramour. On the professional front, he was more conducive to risks as he functioned as a pragmatic negotiator in times of crisis for the colonial government, be it with the Indians or the Crown on the question of proprietors.

Therefore, we see that this period can be viewed as the formative stage in Franklin’s political career. Benjamin Franklin enunciated his ideas of non-sectarianism and practical governance rather clearly but was yet to become a formidable political force.

Chapter 8 | Troubled Waters

Owing to his skills as a negotiator and overall prudent politician, Franklin was sent as an envoy to England to appeal the colonies’ case. This chapter explores his life and experiences in a society far removed from the one he was used to.

Firstly, on the personal front, he befriended and sustained romantic relations with a couple of women, including Polly Stevenson, who would prove to be a lifelong friend to him. As earlier, he projected an avuncular, along with amorous, attitude towards her. He was impressed by her intellectual inclinations, and somewhere tried to find a substitute in her, for Deborah’s lack of these qualities.

London appeared to him as an interesting paradox- disease-ridden and dirty on the one hand, vibrant and cosmopolitan on the other. We see that the intellectual community burgeoned here in privileged spheres such as the Royal Society and in common coffeehouses as well. His interaction in these circles helped him forge some useful friendships with the likes of Dr. John Fothergill, Dr. John Pringle, and William Strahan. These associations would help him immensely in achieving his political goals in London.

Since England’s political scenario was unchartered territory for him, we see that his old tricks failed to gain him progress. He had come to England to appeal against the Penns and privileges of the Proprietors at large. He believed that the American people under the British Crown should have the same rights as those in England. However, he soon made a rude realization that people in Britain did not think so and the Proprietors claim had support in the British courts.

He would go on to reason with the Penns directly but would act distinctly out of character. He would lose his calm and often make far-fetched claims that were not entirely correct. He failed to reach an end with his negotiations but decided not to leave England until he had achieved some ground. This is a classic example of Franklin’s resilience as a diplomat. It would take a while before Franklin would regain composure in his correspondence with the Proprietors and use his old pragmatism to win a compromise. Even though the victory was partial, it was definitely a step ahead.

Franklin can be seen as an interesting character based on his beliefs and demands. He was a professed British royalist, yet his demands against Proprietary privileges in colonies was not in consonance with English beliefs. He theorized that the British saw colonies as resource centers that could be exploited to benefit the mother country. He argued against this and concluded that if Britain treated its colonial subjects with the same regard as its natural citizens, then the colonies would never rebel.

After a 5-year stint at London, Franklin finally decided to leave for home. He had wrapped up his job fairly well, though not as expected. Following a sentimental and emotion-laden farewell with his ‘surrogate family’ of Polly Stevenson and her mother, he finally returned to America and continued his scientific pursuits.

Chapter 9 | Home Leave

After returning to America, Franklin resumed his role as a postmaster. We have explored so far that he entertained a keen interest in travel. Luckily for him, his job allowed him just to do that. Despite his fervent attempts, he could not get his wife to accompany him. This can be attributed to her beliefs against venturing too far from home. It can be said that they both asserted their independence in their own way.

He toured the colonies several times and was familiar with the internal politics in a way that put him in a conducive position to bargain for their rights when the time came. First, such opportunity arose on the question of the Paxton boys, that threatened the outbreak of a religious and social civil war. Franklin came out in vehement opposition of the anti-Indian sentiment and published several pamphlets decrying the brutality. He came in direct confrontation with them and was able to pacify them enough not to unleash the same horror in his town.

We see that his hard line stance to bring the Paxton boys to justice was diametrically opposed to that of the Governor, John Penn, who wanted a negotiation for political benefit. This resurfaced the old antagonism between Franklin and the Penns. As a result, we find that Franklin grew increasingly cynical in his discourse on politics as its unjust arbitrariness dawned upon him. He rallied for a colonial rather than proprietary government, with renewed vigor. As a staunch Royalist, he wanted Pennsylvania to come under the direct Crown rule.

However, he faced much opposition for his views. There were two main reasons for this: the frontiersmen’s preference of a Proprietary government and the Penn family’s reputation as formidable political opponents that was known of, even in England. That did not, nevertheless, dampen Franklin’s resolve and he started a petition campaign against the government. Amid fervent opposition that sought to drag his name through the dirt, he continued his crusade. Therefore, the election season of 1764 was an important year in America’s history of free expression, as it saw its uglier, unrestrained facet.

The elections resulted in a vote in the Assembly to send Franklin back to represent his cause in England. Franklin was more than willing to take up the task for the following reasons: he missed his stint in London, he felt confined in Philadelphia politics, and he had bigger plans for an American union that would require representation in the Parliament. The latter would become important amid news of the Crown planning to levy taxes on colonies. He thought it would be fair to extend citizenship to colonies if they were to be taxed.

He received a hearty farewell as people pinned hope to his efforts. Franklin, on a personal level, did not know what to expect from the trip. We come to this conclusion by his conflicting testimony to his friends, as he told some that he would return in a few months, while some had the knowledge that he did not plan to return at all.

Chapter 10 | Agent Provocateur

On his return to London, the first thing Franklin reconciled with was his ‘surrogate family’ of the Stevensons. He reconnected with Polly and continued sending her letters that portrayed avuncular affection and intellectual flirtation. He also got back with his friends and resumed appearing in their circles. Another important relationship he formed at this time was with his illegitimate grandson, Temple, whom he took under his wing and provided with education.

We will see that Franklin pursued his missions in England relentlessly. In fact, he had his blinders on so tightly that he would not return to America despite the news of his wife’s deteriorating health and would continue his futile fight for 10 years up to the eve of the Revolution. Owing to his political beliefs and allegiances, he had to perform a balancing act between being a royalist who advocated for an imperial rule over the colonies and establishing himself as an American patriot in the face of lack of sympathy from the colonial government.

Franklin found the political atmosphere of England rather bizarre and his old, trusted tricks failed to work there. One of the biggest miscalculations on his part occurred after the passing of the Stamp Act of 1765. It was a tax imposed by the Crown on the colonies, a fact that the populace resented. Franklin took a pragmatic stance and advised that the people cooperate with the new law. However, he misjudged the attitude of the people who were willing to take up arms against the act. A conflict between the colonies’ and Crown’s interests caught Franklin in the crosshairs, who was villainized as an Imperial sympathizer.

While violence brewed back home, Franklin adopted a moderate stance owing to his love for Britain. Moreover, he was more of a smooth negotiator than a revolutionary by nature. However, his goal of making Pennsylvania an imperial colony now seemed far unrealistic than ever. To salvage his tarnished image as a supporter of the Stamp Act, he began a letter writing campaign where he categorically criticized the act and denied ever supporting it.

His moment of redemption came when he was able to present his case directly to the Parliament in 1766. He was able to put forth the social and emotional turmoil of the colonial population in strong and clear words. Therefore, an excellent performance there earned him his reputation back home.

Another political upheaval came with the passing of the Townshend Act. Franklin’s miscalculation this time was two-levelled; drawing a distinction between internal and external taxes, which was actually not respected in the colonies and adopting a position of moderation. He finally gave up a moderate stance when the British government thwarted his aspiration of Pennsylvania ever being free from the Proprietary rule.

Franklin took to writing critical articles against the government and its discriminatory Acts. However, his attack was still focussed on the Parliament rather than the Crown. Therefore, by the end of this turbulent phase, the inconvenience of Franklin’s paradox as a royalist and an American patriot resurfaced.

Chapter 11 | Rebel

Chapter 11 | Rebel

When Franklin faced repeated failures in the political arena, he decided to forsake it for a while. He left in the pursuit of another passion he indulged in with great joy – traveling. He also resumed his scientific inquiries while vacationing around England as he found a subject of interest in the developments of the industrial revolution.

We see from accounts of this voyage that Benjamin’s burgeoning patriotic sentiment often came in conflict with his instilled allegiance as a royalist. For instance, he argued against British sanctions on the colonies by pleading that they would never threaten the British competition. Yet, on his tour of the industries, he wrote detailed descriptions of the manufacturing process in the hope of helping indigenous industries.

At 65, when Franklin found leisure from his professional duties, he took to writing his autobiography. Even though the professed aim of this project was to familiarize his son William with his ancestry and Franklin’s journey from obscurity to prominence, it does not seem to be that limited. Analyzing the writing style which details the processes of his achievements in the way of writing that maintained scope for corrections and additions, reveals that Franklin intended this work for mass consumption. By the time Franklin concluded his voyage of London, he had completed bout 4 chapters of what would turn out to be a lengthy autobiography.

On a personal front, we see that he found paternal affection for another young woman called Kitty, the daughter of his friends, the Shipleys. He would maintain a loving and healthy relationship with her for the rest of his life. At this point, he was also reminded of his grandson Benjamin Franklin Bache, whom he had never met.

Franklin often deemed his ‘surrogate’ relations more highly than he did his real ones. An instance of this can be observed in his behavior towards Benny, his real grandson whom he advised his wife against spoiling and his godson Billy, Polly’s son, whom he talked of very highly. 1774 turned out to be an especially trying time for him as he had begun estranging from his son William and then received the new of wife’s passing away in his absence.

While these developments underscored his life, Benjamin continued his scientific endeavors. Always better at pragmatic experimentation that theorizing, he made initiations into some important scientific themes that would serve as blueprints for subsequent generations of scientists. He, for example, continued his experiments with oil and water that would be a precedent for determining molecular size many years later. The cause of colds, lead poisoning, and saltiness of the ocean are just some of the many phenomena he unearthed in this period.

This was a time when his social philosophy was ripening, and even though it would be many years before he would declare himself an abolitionist, he had begun propounding liberal ideas. On the political front, he gained immense success by dislodging Hillsborough and receiving a land grant in Ohio. Unwittingly, he stirred up radical sentiment in the American colonies when his exchanges with an acquaintance were made public, which portrayed his fervent support for the colonies’ independence.

By 1775, Franklin was ready to leave London. His attempts at any compromise between the colonies and Britain had faded. Therefore, it turned out to be an emotionally challenging voyage for him as he sailed back to a warring America.

Chapter 12 | Independence

Agitations had broken out between British and American contingents, as Franklin sailed towards America in 1775. By the time he reached Philadelphia, the Second Congress was convened, and he was included as a member. The looming question was whether to fight the war for independence or of the assertion of American rights while remaining under British rule. This was a precarious position to be in for Franklin, who was torn between his sentiments as a royalist and an American patriot. He, therefore, chose to keep quiet while the other senators debated on the theme of independence.

He finally broke his silence during a meeting with Joseph Galloway and William Franklin and declared his stance in favor of complete independence for America. This decision was motivated by the several betrayals, personal slights and disappointments he had incurred by the British. It also exemplified the virtues he envisioned to build the ideal American society upon – appreciation of merit, a powerful middle class, liberty, tolerance, frugality, industriousness and respect for the merchant class.

Amidst certain dichotomy where some ministers sought a compromise with the Crown and others had radical ideas of rebellion, Franklin made his position clear by publishing a letter to his friend William Strahan in London. The language was terse and accusing, and its aim was to make public his ideas of America’s future. Even though the letter was not really sent and further correspondences between the friends were mellow and looked for conciliation, the letter did have its desired effect.

As an ardent supporter of an American union, he conceptualized the Articles of Confederation and the Perpetual Union. The kind of federation Franklin proposed was much ahead of its times as it meant the division of powers and a single-chamber Congress to ensure the security of rights and general welfare.

With his experience, managerial skills and visionary character, Franklin became a pillar in the American edifice against Britain. He was an obvious choice to head planning committees that drafted systems for the smooth transition of America into an independent state. Franklin often produced interesting amalgamations of his sharp wit and his political convictions, such as the rattlesnake flag with the motto of ‘Don’t Tread On Me,’ which symbolized American vigor and magnanimity.

When his plans at negotiation were once again thwarted in London following a meeting Lord Richard Howe, Franklin was sent on a secret diplomatic mission to France in order to cajole its alliance. By this time, Franklin’s age had begun to catch up with him, and he accepted the proposal rather reluctantly. He did not keep very well and lacked in vigor and energy.

Yet, he was ambitious about the potential of this trip for America’s diplomatic goals. For his company, he had in tow both his grandsons, Temple and Benny. He hoped that the tour could be a good experiential exercise for both of them and they would prove to be a comforting company to his old soul. Therefore, with a mission in sight, the old Benjamin Franklin set sail for France.

Chapter 13 | Courtier

After an uncomfortable voyage that took a toll on the aged Franklin, he finally touched the French coast. He tried to maintain a low profile at the small towns he visited so that he could test the receptiveness of the French Court for American ministers before initiating anything. However, as we have seen earlier, Franklin had become one of the most famous Americans in Europe through his scientific discoveries and achievements as a politician. Therefore, he was received grandly and was immediately a fixture at social gatherings.

Franklin sought to leverage his fame to further his political interests. France’s long history of hostility with England would make it a perfect ally, only if Franklin could persuade them. France received Franklin with open arms, and he returned the adoration by exalting French civility in his writings. He soon made himself at home thereby setting up a court of sorts.

He made a new set of friends who pampered him and was met by new colleagues, whose conflicting views made his work interesting.

Since American opposition had significantly increased and was buttressed by vigorous diplomatic activity, England deployed a sophisticated espionage system in order to gather information on American movements. Franklin was made wary of this threat as soon as he began operations in France. He even was confronted with the presence of a certain Edward Bancroft who functioned as a spy for the British for a long time before being found.

Franklin had a rather naive response to this matter saying that an honest man had nothing to fear, but it can be fathomed that such a statement was possible only because the spy’s information was unable to do any serious damage.

Franklin soon found a reluctant ally in Comte de Vergennes, the French Foreign Minister, who shared his dislike for England and faith in the new nation. He also liked Franklin on a personal level due to his bourgeois sensibilities that Vergennes appreciated. Franklin, for his part, found a perfect blend of idealism and realism to appease the French minister. He professed a calculated balance- of- power calculus to portray the feasibility of a Franco- American alliance. On the other hand, he exalted American values and sought to establish faith in it by presenting it as an asylum in the face of tyranny. He also began recruitments for the American army while still in France, and was able to secure the loyalty of men who would prove pivotal in the Revolution.

The French soon agreed to an alliance but awaited Spanish acceptance as the two had made a pact to act in concert. Meanwhile, Britain initiated secret negotiations with the Americans to avoid further confrontation. Franklin, with keen diplomatic acumen, pitted the French against the English by leaking information. France, therefore, agreed to co-operate without Spanish support and treaties of friendship and alliance were signed.

Thus, the course of the Revolution was finalized and also of the world’s balance of power, even though it was not realized at that stage.

Chapter 14 | Bon Vivant

After securing a French alliance for the American cause, Franklin was in a much secure position as a diplomat. During this time, he made several acquaintances that would leave a lasting impact on him. One of them was John Adams, who joined as an American commissioner. His equation with Franklin can be seen as a rollercoaster, where the two went through a series of emotions ranging from resentment, to amusement to finally, admiration. They had contradictory personalities but found common ground in their Puritanical beliefs.

Another important acquaintance Franklin made was the famous French philosopher, Voltaire. This match, interestingly, was designed by an enthusiastic public imagination that saw them as fated to meet. Their meetings caused a frenzy of fans and were profusely written about. Franklin’s association with the French intelligentsia and literati prompted him to join a lodge where his ideas against absolutism found popular acclaim.

True to his character, he forged some lasting and meaningful relationships with the opposite sex in Paris. These relationships were amorous but limited to the intellectual and spiritual level. Franklin’s societal stature made him instantly attractive to aristocratic women who sought ways to make his acquaintance. These affairs, often sexually charged though not fully consummated, fed a flurry of scandalous stories.

He got into emotionally serious relationships, one with a Madame Brillon and the other with Madame Helvétius. However, his reluctance to commit kept him from going through with either. These tumultuous relations had the effect of distancing these women from him, but on Franklin, it was quite the opposite: he felt young again, at least in spirit.

Therefore, we see that while Franklin attended to a lively social life in France, he unknowingly began distancing his real family. His correspondences with his daughter were often didactic and disapproving and were received with replies that reflected disappointment and dejection. He was much softer with his grandchildren although instructive just the same.

Over time, his frequency of correspondence with them also declined, and its direct impact on Benny was that he drew in himself and became rather reserved. A change of company would see a breakout of his rebellious streak, which was received with an admonition by Franklin. For Temple, Franklin was incessantly trying to play matchmaker by hitching him to one of the Brillon daughters. However, Temple’s descent proved to be a roadblock, and while things could have been worked out, Temple had already embarked on his way to becoming a philanderer.

Apart from social obligations, Franklin also found time to pursue his scientific endeavors. However, this time they were tinged with humor and were for the sake of amusement, like his study on the causes and cures of farts. He rejuvenated his admiration for chess and was known to play until the wee hours of the morning. He believed that chess was a good exercise for the brain and taught one foresight and circumspection.

We, therefore, observe that Franklin’s character had evolved much and was now true to his age. Just like an old man with leisure, he was indulging in his interests and cultivating a healthy social life. He also kept his political beliefs to himself until asked for or as he deemed them necessary to share.

Chapter 15 | Peacemaker

During his time in France, Franklin had done everything to make himself a favorite at the French Court as well as the social circles. As a result of this, the French themselves lobbied for him in 1778 to be sent as minister plenipotentiary, and he was guaranteed the job. This result also upset a few that did not believe that Franklin’s candidature befits the bill, like John Adams and Arthur Lee. However, they had no choice but to find a middle ground and work with Franklin.

He came across several interesting characters during his stint as the American ambassador. One of them was John Paul Jones, an adventurous and rogue lad picked to head the American fleet in case of a British invasion. Jones was a reckless man who acted on whims, but this also gave him immense courage that Franklin believed would be necessary for such an expedition.

He was also an incorrigible flirt, which landed him in a series of scandals. Franklin adopted several methods to tame Jones, often sending him didactic letters that instructed him to use restraint in his dealings. When Jones proved his mettle in a naval battle against the British, Franklin developed more admiration for him and would even go on to defend him in disputes.

America needed financial resources to aid the Revolution, and it became rather desperate by 1780. Franklin, therefore, had to act as a representative of this desperation to the French. He made personal pleas, invoked idealism and national interest to get the French to loosen their purse strings. He could not get them to agree to the sum he demanded, though he did secure a substantial amount. Despite this victory, a fervent opposition against him that brewed back home disheartened Franklin. His adversaries pegged him to be too old and ineffective to take charge. That did not go down well with him, and he decided to resign.

However, the Congress was smarter than letting go of an experienced diplomat at a crucial time. So, this request was rejected. Additionally, he was given the charge of peace negotiator with Britain. Britain still wanted to negotiate terms of independence, while Franklin strongly put forward America’s non-negotiable stance. In fact, he proposed that Britain should offer reparations to America for the years of damage that it had inflicted and one way of doing so would be to cede Canada.

A complex balance-of-power game ensued where Britain, France, and America weighed the consequences of such a treaty. Soon a peace conference was initiated for all the stakeholders.

Franklin was clear about the terms he on which he wanted America’s independence. Therefore, he was especially annoyed when France was negotiated vicariously, and America was not involved directly. He felt that American dignity was being belittled. Therefore, he gained special permission to hold peace negotiations with Britain separately. After enduring a lot of back channel intrigue, Franklin found just the right moment to propose his peace plan when people more receptive of his ideas came to power in Britain.

The details of Franklin’s plan are worth mentioning. He divided his peace plan into two parts that contained both non-negotiable and negotiable terms. Under the ‘necessary’ provisions he demanded independence for America, which would be absolute in every sense, removal of British troops, autonomous and secure borders and fishing rights off the coast of Canada. Under the ‘advisable’ provisions, he asked for reparations from the British, ceding of Canada, acknowledgment of British guilt and a free trade agreement.

The plan was tabled, and the negotiations began. Britain was unwilling to ratify the plan in its original form and wanted further dialogue on both categories. France’s position as a reliable ally also came under doubt and led to a rift between Jay the skeptic, and Franklin, the believer. It would take some more espionage to coax Britain into making the terms of the treaty clearer so that American dependence on French help could be diminished and it would be Jay’s endeavor that would achieve it. Following this, he and Franklin were back on the same page and resumed working towards a common goal.

However, this accord came at the expense of peace in French and American relations and on Franklin fell the onus to explain to Vergennes about this decision. He did so by writing a letter that is considered to this day a diplomatic masterpiece. After that, there was little Vergennes could do to stall the proceeding of peace negotiations and eventually gave way. Therefore, Franklin was successful in securing a peace treaty with England, without endangering relations with France; a feat only a man of his political acumen could have achieved.

Having overcome this Herculean task, Franklin retired himself to the leisures of life. He found time to indulge in his family and called Benny to stay with him at Passy. For Temple, he continued to pull strings to secure a good office for him. This time was also conducive for him to resume his scientific pursuits that he had been away from for quite some time. The French were just as intrigued with science as he was and so he found ample opportunity to indulge himself.

He enjoyed the marvel of hot air balloons and perfected the design of bifocal lenses. He also continued writing anti-elitist literature and remained a crucial part of America’s independence proceedings. He also continued to work on his autobiography well into 1784, and he was 50% done with the project by that time.

Soon, it was time for him to return to America, but his bad health and affection for French society made him reluctant. However, when he received the news that his resignation had been approved by the Congress and that his efforts to secure an overseas appointment for Temple were futile, he decided to go back. Franklin conducted elaborate formalities of exchanging gifts and pleasantries with his high society friends and acquaintances, which included the King and Queen of France. He finally bid adieu to France on July 12 and was sent off by tearful eyes of his many admirers.

Chapter 16 | Sage

From accounts of his voyage to America, we can gather that he had finally let his age catch up with him. He did not attempt any studies nor made any observations. It was as if he was finally at peace, having completed all his duties. He also forsook work on his autobiography for that time. He now completely dedicated his time and effort to scientific experimentation. What resulted was a detailed budget of his maritime observations, replete with sketches.

He arrived in Philadelphia in 1785 and was received with great pomp and show by a large crowd. He soon settled into his Market Street home, surrounded by family and admirers. Despite his age and ensuing immobility, he was as sociable as ever and resumed meetings of old associations. He also went on a building spree and remodeled houses that he owned on Market Street. He installed a remarkable library there, equipped with some fascinating scientific implements, all of which were Franklin’s inventions.

It was almost impossible to keep Franklin away from an active political life, sometimes by his own insistence and otherwise by his admirers. He was soon elected president of the state executive council in Pennsylvania and was pleasantly surprised to find his popularity intact after so many years. He became part of the Constitutional Convention, whose task it was to draw up a final constitution for independent America.

He did not let his age or bad health hinder his work and took his seat every morning. He adopted wry storytelling over ostentatious oratory which was exemplary of the gravity he had gained with age.

He was a strong supporter of democracy and embodied the values of Enlightenments. He also had unparalleled experience in world affairs.

These qualifications made sure that his suggestions were always regarded even if they seemed incredulous to some. He professed compromise as a virtue for a nation that was proud of its diversity. This belief had helped him win battles in life. However, the one time that he forsook the value of compromise was also one of the most important ones on the issue of slavery.

Franklin, aged at 82 and having achieved the pinnacle of political success and recognition, had every reason to retire. However, his pride, by his own admission, still made him appreciate public ardor. Therefore, he accepted the renewal of his state presidency for another year. His swan song to a long and successful political career was to be his public mission against slavery. He presented an abolition petition in 1790, which pleaded for the recognition of the equality of man. It was an emotionally charged literature that sought to plead with reason. However, his petition by denounced by supporters of slavery and the Congress also refused to act on it.

Towards the end of his life, his faith in his religion became firmer than ever. Franklin preached indulgence in religion, but his reason for doing so also exemplified his rational beliefs; that it helped people behave better. He was an apostle of tolerance and left statues of this belief in the form of funds that he built for every religious sect in Philadelphia. Letters from the last days of his life are replete with his religious beliefs.

The very last letter that he wrote was to Thomas Jefferson, his spiritual heir to the nation.

His condition began to worsen and reached an all-time low. The final blow came on 17th April 1790, when Benjamin Franklin succumbed to an abscess which had burst in his lung. His funeral procession was a grand display of everything that the great man had achieved in life; throngs of admirers led by clergymen of every faith walking hand in hand to pay respect to one of the greatest Americans to have ever lived. Benjamin Franklin was a total badass indeed.