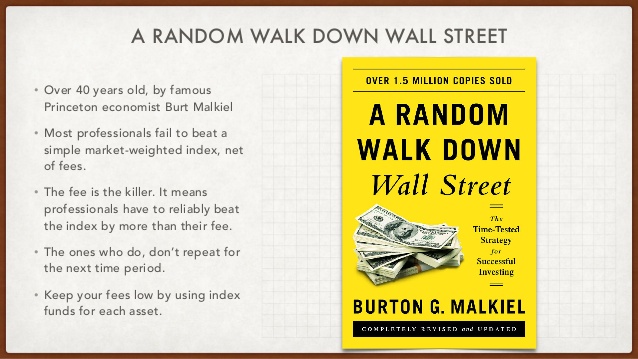

[The following should not be used as the basis for any financial transactions. But this is a synopsis of A Random Walk Down Wall Street. The book is the “cat’s meow” for understanding how Wall Street works. Malkiel’s conclusion is that it makes more sense to invest in an Index (passive investment) in the long run given the underperformance of active investors…I don’t 100% agree or disagree; I’m merely seeking to understand.]

“My initial interpretation of this book is that it further strengthens what I have studied in the social sciences (political science, economics, history). The book points out that humans are un-predictable in most instances. Perhaps humans are emotional creatures who occasionally act rationally, but only when they aren’t emotionally attached to the decision. Whether it’s the Berlin Wall coming down, or the Enron financial debacle, predicting future events seems like it would be something tough to do. And of course, humans are beholden to a lot of things that we do not fully understand from blood sugar levels to our daily dosage of mainstream media propaganda. Perhaps the way to predict the markets is still elusive, despite efforts made by various people.” – Professor Nerdster

Chapter 1: The Guide and His Core Idea: Shit is Random

This chapter talks about the qualification of Professor Malkiel as a guide, as well as, about investment and meaning of Random Walk Down Wall Street.

Professor Malkiel validates his expertise based on an impressive career. His first job was as a Market Professional with one of Wall Street’s leading investment firm, then he became an Economist specializing in securities markets and investment behaviour, and lastly he became as a lifelong investor and successful participant in the market. And a Prof at Princeton in New Jersey.

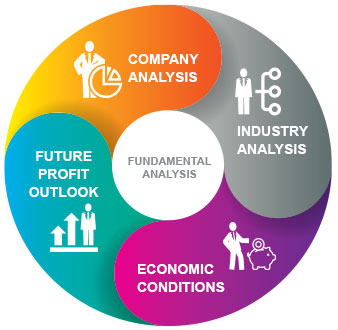

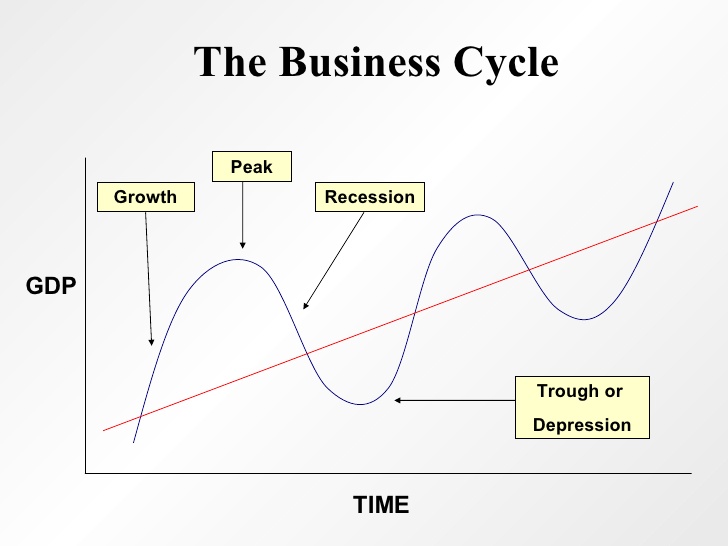

Random Walk is one in which future steps or directions cannot be predicted on the basis of past actions. When you apply this to the stock market, it means that short-run changes in stock prices cannot be predicted. This splits the professionals from academics and the “pros” have created their own techniques. Market professionals have two techniques: fundamental and technical analysis, while Academics created the “new investment technology theory”. Later on, the two joined forces with the conclusion that the stock market can be predictable somewhat but there are pockets of inefficiency….

Academics today accept what Malkiel is saying in this book: “predicting the future is kinda tough, eh?” Flash back to the professor’s lounge, the top finance professor G at B-school X says “We need jobs so let’s use complex statistical methods to map out human behaviour and stock performance because, while that only works randomly, humans are emotional after all, we need jobs and we can say ‘it’s a learning tool’ and we can then get paid!” Finance professor Y smiles, “Right, I mean we do not have much predictive power, otherwise we would be working in the industry right?” And everyone laughed because they know that even portfolio managers can’t predict the future mathematically.

Professor Malkiel explains in this chapter that this book is not a book for speculators. He even expounds the difference between investing and speculating distinguishing it from its definition. Investing is a method of purchasing assets to gain profit in the form of reasonably predictable income like dividends, interest, or rentals, and appreciation over the long term. Investing involves time period for the investment return and predictability of the returns while speculation isn’t.

Professor Malkiel explains in this chapter that this book is not a book for speculators. He even expounds the difference between investing and speculating distinguishing it from its definition. Investing is a method of purchasing assets to gain profit in the form of reasonably predictable income like dividends, interest, or rentals, and appreciation over the long term. Investing involves time period for the investment return and predictability of the returns while speculation isn’t.

This book is not promising to make you rich but will help nourish and educate you about investing. It even gives a preview of the importance of inflation and gives suggestions that even with inflation, investors should not dismiss the possibility that growth in valuation can be over stated, for example.

This book is not promising to make you rich but will help nourish and educate you about investing. It even gives a preview of the importance of inflation and gives suggestions that even with inflation, investors should not dismiss the possibility that growth in valuation can be over stated, for example.

Investing requires a lot of work, no mistake about it. You should embrace the fact that investing is fun. It is exciting to see your investment returns and how well they do.

All investment returns are dependent. It’s a gamble, you can only know your success if you have the ability to predict the future.

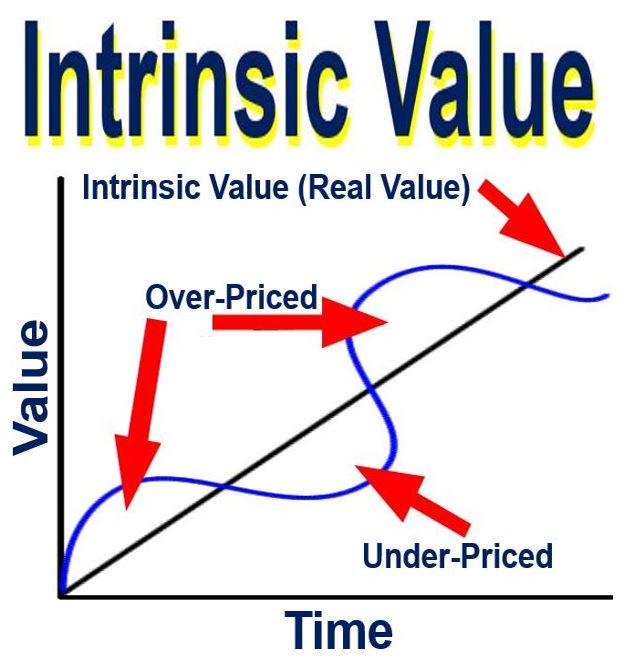

For pros in the investment community, they use two approaches to asset valuation: the firm-foundation theory or the castle-in-the-air theory. Professor Malkiel explains the difference between the two in this chapter.

The firm-foundation theory argues that each investment has a firm anchor of something called intrinsic value. It means that when market prices fall down, a buying or selling opportunity arises. He explains that with the use of The theory of Investment Value, wherein they determine the intrinsic value of stock and then use the concept of discounting in the process. Discounting basically involves looking at the income backward rather than seeing how much money you will have in the next year; you look at the money expected in the future and see how much less it is currently worth. This approached is in accordance with John B. Williams’ study. Malkiel even explicates that intrinsic value of a stock is equal to the present or discounted value of all its future dividends. This theory is respectable in academia, taught in the MBA and the CFA and is best with common stocks.

The firm-foundation theory argues that each investment has a firm anchor of something called intrinsic value. It means that when market prices fall down, a buying or selling opportunity arises. He explains that with the use of The theory of Investment Value, wherein they determine the intrinsic value of stock and then use the concept of discounting in the process. Discounting basically involves looking at the income backward rather than seeing how much money you will have in the next year; you look at the money expected in the future and see how much less it is currently worth. This approached is in accordance with John B. Williams’ study. Malkiel even explicates that intrinsic value of a stock is equal to the present or discounted value of all its future dividends. This theory is respectable in academia, taught in the MBA and the CFA and is best with common stocks.

The Castle-in-the-Air Theory of investing concentrates on psychic values. According to John Maynard Keynes, professional investors prefer to devote their energies not to estimate intrinsic values, but rather analyze how the crowd of investors is likely to behave in the future and how they tend to build their dreams: on castles in the air and selling stock to the ‘greater fool’. Keynes also applied psychological principles rather than financial evaluation to study the stock market.

Chapter 2: History Gets Repeated in New Ways All the Time

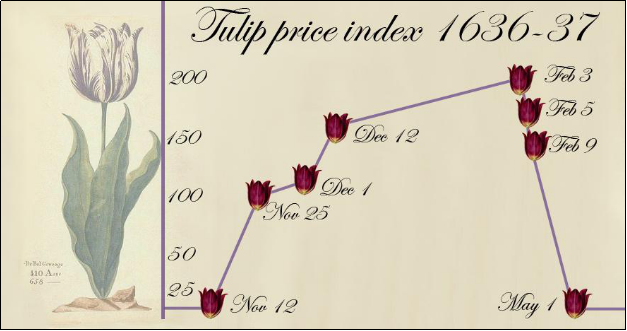

Greed becomes an essential feature in human history, it’s not a bug but a feature to use computer terminology. People use money in any activity with the assumption that it can reach their dreams. Although, the castle-in-the-air theory can explain such speculative activity, outguessing the reactions of a crowd is a most dangerous game. History does teach this lesson, over and over..

Unsustainable prices may persist for years but eventually, reverse and this reversal is often very sudden. The bigger the activity, the greater the results of the fall of the so-called cloud castle. Only a few ‘builders’ can anticipate and escape without losing a great deal of a money when everything falls apart.

Example of this happening in the past. First, the Tulip-Bulb Mania which is one of the most spectacular get-rich-quick schemes in history. Dutch speculators invested in tulips, expecting to increase their wealth, even selling their personal belongings to obtain what they think/thought was a smart investment, considering offers that are hard to resist that later on lead to deflation which grows at a rapid pace. The end result is that the price of tulips was a lot of wealth.

Example of this happening in the past. First, the Tulip-Bulb Mania which is one of the most spectacular get-rich-quick schemes in history. Dutch speculators invested in tulips, expecting to increase their wealth, even selling their personal belongings to obtain what they think/thought was a smart investment, considering offers that are hard to resist that later on lead to deflation which grows at a rapid pace. The end result is that the price of tulips was a lot of wealth.

The key is applying the greater fool principle, all you need is someone more foolish than you to buy the stock you are selling in order for you to make a profit and get out from under the cloud castle when it collapses…hard to time that of course.

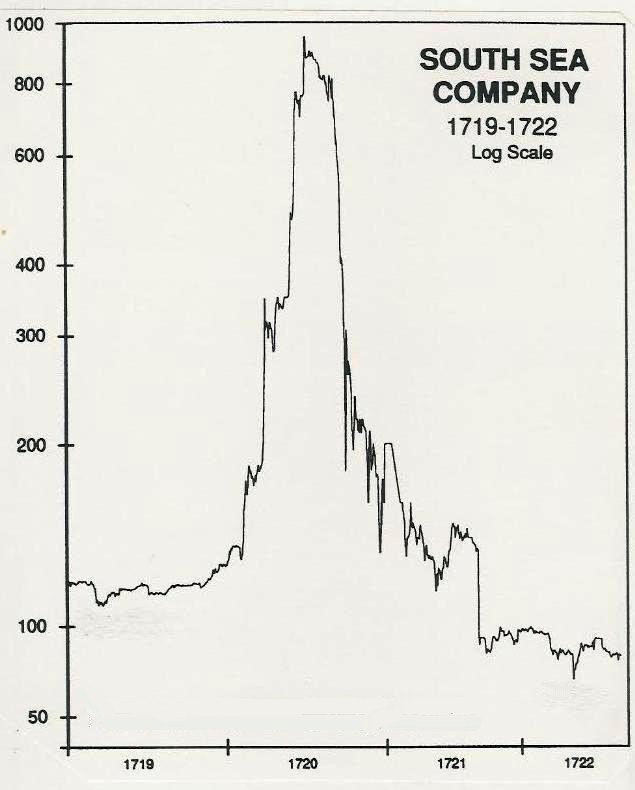

In South Sea Bubble there was a lot of prosperity in Britain as they led the world in financial and accounting innovation and also were an island, that was hard to invade etc etc. As an economy improves, the citizenry tend use their money for investment. By greed, companies arise where they fight with each other to prove who is the better investment; giving offers that are hard to resist. Apparently, this lead the South Sea Company to fall like another castle in the air, making the public suffer. To protect them from further abuses, the Parliament passed the Bubble Act that forbids the issuing of stock certificates by companies.

In South Sea Bubble there was a lot of prosperity in Britain as they led the world in financial and accounting innovation and also were an island, that was hard to invade etc etc. As an economy improves, the citizenry tend use their money for investment. By greed, companies arise where they fight with each other to prove who is the better investment; giving offers that are hard to resist. Apparently, this lead the South Sea Company to fall like another castle in the air, making the public suffer. To protect them from further abuses, the Parliament passed the Bubble Act that forbids the issuing of stock certificates by companies.

In The Florida Real Estate Craze, Professor Malkiel discusses the US as the land of opportunity. The US continued the British emphasis on freedom and growth. The country had been experiencing incomparable prosperity. Their mood of optimistic and faith in the business led to widespread enthusiasm about real estate and the stock market. But, inevitably the boom ended in 1929. New buyers could no longer be found and prices softened and there was a down turn, suddenly a mortgage is ‘under water’ and it doesn’t look so sharp to invest in all of the sudden…

With Florida’s experience, investors should avoid a similar misadventure on Wall Street. But, Florida is the start of what comes next; stock-market became a national pastime, the market’s percentage increase and the price rises for the major industrial corporations.

Not everybody is speculating in the market, but still, the speculative spirit is as widespread as it is intense. Remember that speculating = gambling. More importantly, stock-market speculation is central to the institutionalization of gambling in Anglo-culture. Unfortunately, there are hundreds of operators glad to help the public to construct their dreams. Manipulation of the stock exchange happens. Example of which is the operation of investment pools where they appoint a pool manager that promises not to double-cross each other through private operations. There is a kick-ass book on this topic call Business Adventures which I will be writing a synopsis of in the future.

Not everybody is speculating in the market, but still, the speculative spirit is as widespread as it is intense. Remember that speculating = gambling. More importantly, stock-market speculation is central to the institutionalization of gambling in Anglo-culture. Unfortunately, there are hundreds of operators glad to help the public to construct their dreams. Manipulation of the stock exchange happens. Example of which is the operation of investment pools where they appoint a pool manager that promises not to double-cross each other through private operations. There is a kick-ass book on this topic call Business Adventures which I will be writing a synopsis of in the future.

Professor Malkiel points out that a study of these events can help equip the investors for personal survival. Losers are those who are unable to resist being carried away. It is not that hard to make money in the market, what is hard is to avoid the temptation of throwing your money into any and all speculative activities. The ability to avoid such mistakes is probably the most important factor in maintaining one’s capital and allowing it to grow. According to Professor Malkiel, the lesson is so obvious and yet so easy to ignore.

Chapter 3: Stock Valuation has been Bullshit for a long time

This chapter discusses the Stock Valuation from the sixties through the nineties involving examples and explanations of certain events.

Professor Malkiel starts by relating certain peculiar events, including when General Electric announced about the diamond that was unsuitable for sale but the shares still rise. He elaborates and cites the growth in stock in the new era where investors created any new offering could increase the valuation and thus the stock price through trading. There is this hilarious pattern from 1959 to 1962 called the of the tronics boom, because the offerings include the word electronics in their title, even though have nothing to do with electronics. The name was the game. This form of manipulation highlights how few investors knew what was really going on and just picked ‘good sounding’ investments.

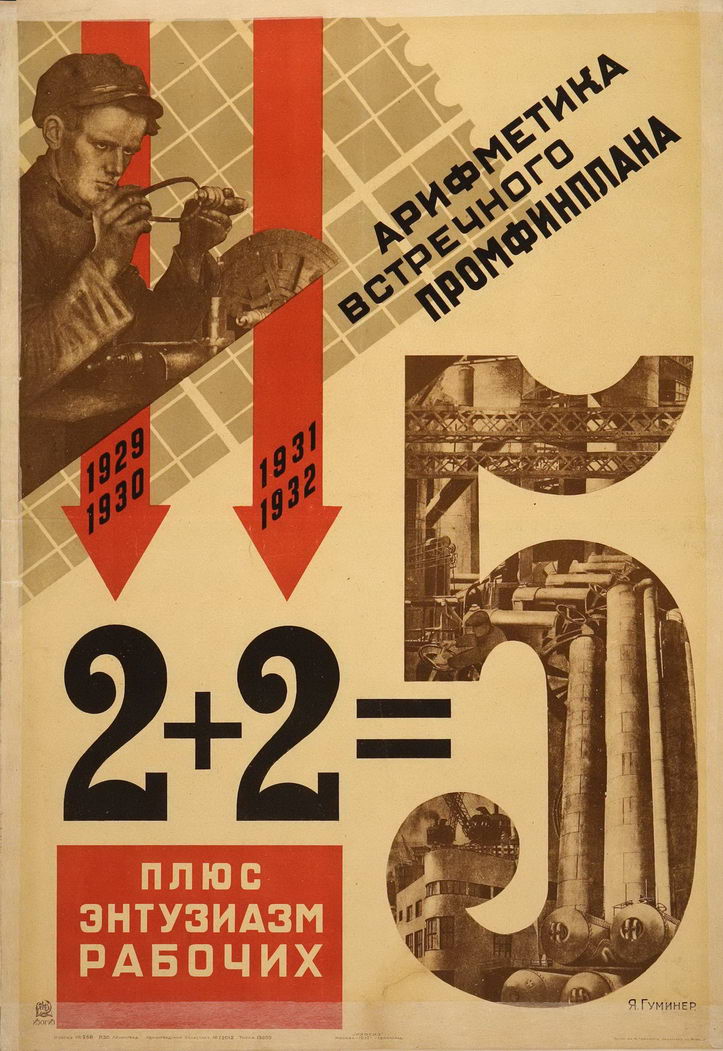

Synergism is the quality of having two plus two equal five. Thus, two separate companies with earning power which might produce a consolidated higher value. This profitable new creation is often called conglomerate. The merger would allow for the achieving of a greater financial strength and enhances marketing capability. Definitely can work out if executed well and the cultures are similar enough.

Synergism is the quality of having two plus two equal five. Thus, two separate companies with earning power which might produce a consolidated higher value. This profitable new creation is often called conglomerate. The merger would allow for the achieving of a greater financial strength and enhances marketing capability. Definitely can work out if executed well and the cultures are similar enough.

In light of this the commandments for Fund Managers are simple: Concentrate your holdings in a few stocks and don’t hesitate to switch the portfolio around if there is more desirable investment appearing on the horizon. Make sure that the market recognizes the beauty of your stock now-not far into the future. Hence, the birth of the so-called concept stock.

He further talks about the Nifty Fifty. This is big capitalization stocks which means that an institution could buy a good-sized position without disturbing the market. The craze ends like all others. The problem is simple, the stocks become overpriced and collapse like any other cloud castle i.e. the greater fools cannot be found.

The Roaring Eighties have its fair share of excesses, and investors paid the price for building their dreams. The decade starts with another new-issue boom.

Professor Malkiel explains the success of this high-technology new-issue, the almost perfect replica of the 1960s episode. For investors, initial public offerings are the hottest game in town. The stocks are not quite ready and needed some development. They encounter significant technological obstacles that hinder the stock’s valuation.

Concepts of Biotechnology Bubble. This technology promises to produce a group of products where the valuation levels of stocks reach previously unknown levels to investors and since biotech companies have no current earnings and little sales, new valuation methods need to be formulated.

Concepts of Biotechnology Bubble. This technology promises to produce a group of products where the valuation levels of stocks reach previously unknown levels to investors and since biotech companies have no current earnings and little sales, new valuation methods need to be formulated.

The lessons of market history are clear, according to Professor Malkiel. Style and fashions often do play a critical role in pricing. The stock market at times adjusts well to the castle-in-the-air theory. For this reason, the game of investing can be extremely dangerous.

The Nervy Nineties

Japan’s real estate and stock markets is considered one of the most spectacular booms and busts. During their growth, firms often make more money from trading stocks than from producing goods, but the collapse destroys the myth that Japan was different and its asset prices would always rise.

The Internet Craze of the Late 1990s

The Internet Craze of the Late 1990s

Stocks for companies “on the Internet” could rise tenfold in a single year, and this fascinated investors. The industry is strongly competitive and investors did not focus on the great risks that small companies may have faced. No one can deny that the Internet is a big deal, that it will enjoy explosive growth, but in a highly competitive industry, there will be many losers and only one victor per vertical (sub-category i.e. Facebook for social media, Google for search etc). Many firms like Pets.com, were too speculative about the potential of increased information access to be profitable, oh and also a bag of dog food is very expensive to mail….

As Professor Malkiel‘s final word for this chapter, it seems that markets at times can be irrational, that we should abandon the firm-foundation theory. The market eventually corrects this irrationality. It eventually sees the true value and main lessons that investors must notice.

Chapter 4: Four Determinants that Affect Share Price

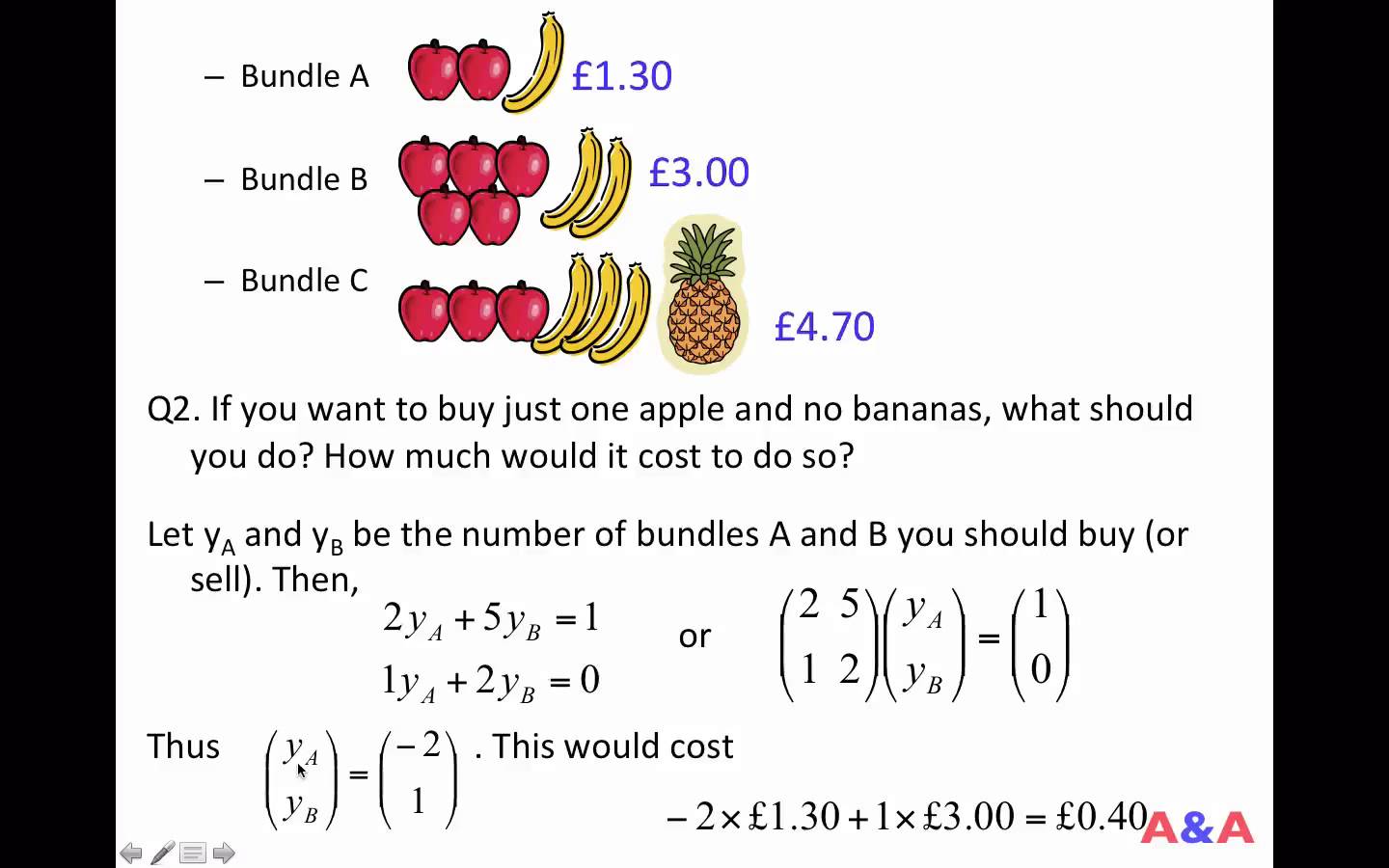

In the first chapter, the firm-foundation theorists viewed the worth of any share as the present value of all dollar benefits the investor expects to be received from it. ‘Present’ means that dollars expected and those anticipated later on must be discounted. In a very real sense, time is money, because if you have the money now you could be earning interest on it.

He even further explains that many corporations preferred to institute stock buy-back programs meaning, those activites tend to increase capital gains and the growth rate of the company’s earnings and stock price. It makes options more valuable.

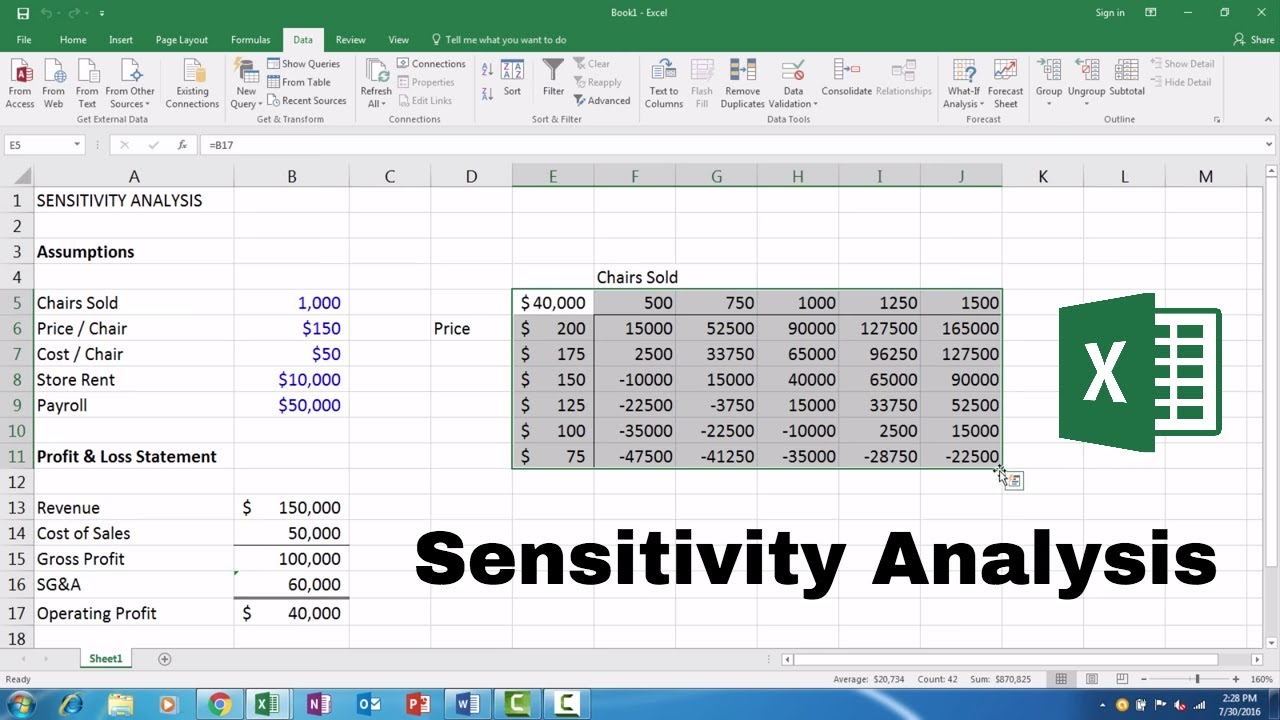

Professor Malkiel believes there are major four determinants that affect share value. Each determinant has its rule:

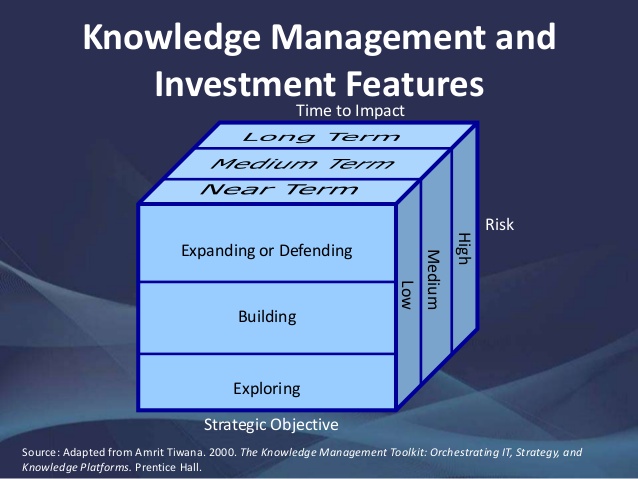

![]() The expected growth rate: A rational investor should be willing to pay a higher price for a share, the larger the growth rate of dividends and earnings. A rational investor should be willing to pay a higher price for a share the longer an extraordinary growth rate is expected to last.

The expected growth rate: A rational investor should be willing to pay a higher price for a share, the larger the growth rate of dividends and earnings. A rational investor should be willing to pay a higher price for a share the longer an extraordinary growth rate is expected to last.

The expected dividend payout: A rational investor should be willing to pay a higher price for a share, other things being equal, the larger the proportion of a company’s earnings that is paid out in cash dividends.

The expected dividend payout: A rational investor should be willing to pay a higher price for a share, other things being equal, the larger the proportion of a company’s earnings that is paid out in cash dividends.

The degree of risk: A rational investor should be willing to pay a higher price for a share, other things being equal, the less risky the company’s stock. Risk plays an important role in the stock market. It also affects the valuation of a stock. The more respectable a stock is the less risk it has and the higher its quality. But, Professor Malkiel states that it is impossible to measure the risk. For most investors, you value the stable returns and not speculative hopes.

The degree of risk: A rational investor should be willing to pay a higher price for a share, other things being equal, the less risky the company’s stock. Risk plays an important role in the stock market. It also affects the valuation of a stock. The more respectable a stock is the less risk it has and the higher its quality. But, Professor Malkiel states that it is impossible to measure the risk. For most investors, you value the stable returns and not speculative hopes.

The level of market interest rates: A rational investor should be willing to pay a higher price for a share, other things being equal, the lower are interest rates.

He further cites that in using and testing these rules there are two Important Caveats or warnings to consider:

He further cites that in using and testing these rules there are two Important Caveats or warnings to consider:

Warning 1: Expectations about the future cannot be proven in the present: Predicting future earnings and dividends is dangerous. It requires not only the knowledge and skill but also the intelligence of a psychologist and persuasion sciences. It is extremely difficult to be objective. The point is, no matter what you use for predicting the future, it always rests in part on the uncertain assumption.

Warning 2: Precise figures cannot be calculated from undetermined data: The longer one projects growth, the greater the stream of future dividends. The point is that the mathematical accuracy of a formula is based on the tricky ground of forecasting the future. They are estimates what might happen in the future, and depending on that, you can convince yourself to pay any price you want for a stock.

These rules and caveats were tested where Professor Malkiel cites examples and gives a conclusion that with these, market prices seem to behave in a way, that can lead to expectation. It is comforting to know that to this extent there is an underlying rationality to the stock market. He attaches an additional caveat: What’s growth for the goose is not always growth for the gander.

Fundamental considerations do have an influence on the market price: the price-earnings multiples are influenced by expected growth, dividend payouts, risk, and the rate of interest. Higher expectations of earnings growth and higher dividend payouts tend to increase price-earnings multiples. Higher risk and higher interest rates tend to pull them down. There is a logic to the stock market. Stock prices tied to have fundamentals but this is easily pulled up and dropped at random. It seems very sensible that both views of security pricing tell us about the actual market behavior: 1) expectations about the future cannot be proven in the present, 2) precise figures cannot be calculated from undetermined date.

Fundamental considerations do have an influence on the market price: the price-earnings multiples are influenced by expected growth, dividend payouts, risk, and the rate of interest. Higher expectations of earnings growth and higher dividend payouts tend to increase price-earnings multiples. Higher risk and higher interest rates tend to pull them down. There is a logic to the stock market. Stock prices tied to have fundamentals but this is easily pulled up and dropped at random. It seems very sensible that both views of security pricing tell us about the actual market behavior: 1) expectations about the future cannot be proven in the present, 2) precise figures cannot be calculated from undetermined date.

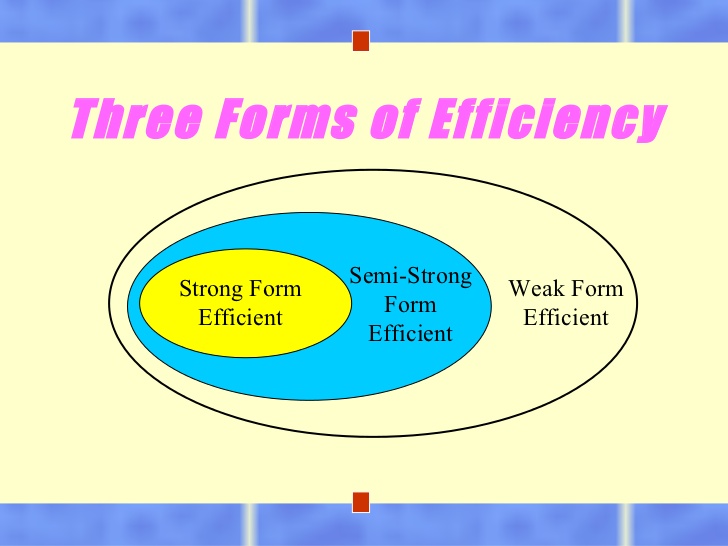

Chapter 5: The Weak, Semi Strong and Strong forms of Efficiency

In this chapter, Professor Malkiel starts the discussion about the three versions of random-walk or efficient-market theory. The weak, the semi-strong, and the strong. All these three embrace the general idea that except for long-run trends, future stock prices are difficult, if not impossible, to predict. The weak, you cannot predict future stock prices on the basis of past stock prices; in the semi-strong, you cannot even utilize published information to predict future prices and; in the strong, nothing, can be of use in predicting future prices. He further states that the weak form attacks the technical analysis, and the semi-strong and strong forms argue against many of the beliefs held by those using fundamental analysis.

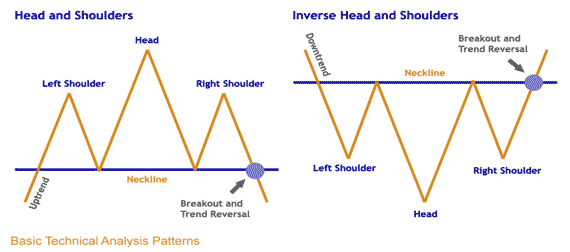

Technical analysis is the method of predicting the appropriate time to buy or sell a stock using essentially the making and interpreting of charts. The chartists study the past for a clue to the direction of future change. They believe that the market is only 10 percent logical and 90 percent psychological.

Fundamental analysis is the technique of applying the principles of the firm-foundation theory to the selection of individual stocks. It takes the opposite of Technical as fundamentalists seek to determine an issue’s proper value.

Principles of Technical Analysis

- All information about earnings, dividends, and the future performance of a company is automatically reflected in the company’s past market prices.

- Prices tend to move in trends: A stock that is rising tends to keep on rising, whereas a stock at rest tends to remain at rest.

Why is charting supposed to work? Professor Malkiel shares an explanation of why technical analysis/charting is supposed to work: First, it has been argued that the crowd instinct of mass psychology makes it so. When investors see the price of a speculative favourite going higher and higher. Second, there may be unequal access to fundamental information about a company. When some favourable piece of news occurs, it is alleged that the insiders are the first to know and they act, buying the stock and causing its price to rise (insider trading in my opinion).

Why Might Charting Fail to Work? According to Professor Malkiel, first, it should be noted that the chartist buys in only after price trends have been established, and sells only after they have been broken. Second, such techniques must ultimately be self-defeating. As more and more people use it, the value of any technique depreciates.

Chartists now use the services of a personal computer to put their data together. They are now known as Technicians where individuals can easily access the charts for different time periods.

Professor Malkiel illustrates the difference between the technician and the fundamentalist; wherein, the technician is interested only in the records of the stock’s price, while the fundamentalist’s primary concern is with what a stock is really worth; its true value.

Why Might Fundamental Analysis Fail to Work? There are three potential flaws that the author cites: First, the information and analysis may be incorrect, Second, the security analysts’ estimate of value may be faulty and third, the market may not correct its mistake and the stock price might not converge to its estimated value.

There are rules that are developed using Fundamental and Technical Analysis Together:

- Buy only companies that are expected to have above average earnings growth for five or more years;

- Never pay more for a stock than its firm foundation of value and;

- Look for stocks whose stories of anticipated growth are of the kind on which investors can build castles in the air.

Chapter 6: Predicting the Future Using Charts is not too smart…

Professor Malkiel elaborates about Technical Analysis where they build their strategies upon dreams and expect their tools to tell them which castle is being built and how to get in on the ground floor. By stating some examples, Professor Malkiel comes up with two considerations:

- after paying transactions costs, the method does not do better than a buy-and-hold strategy for investors, and;

- it’s easy to pick on.

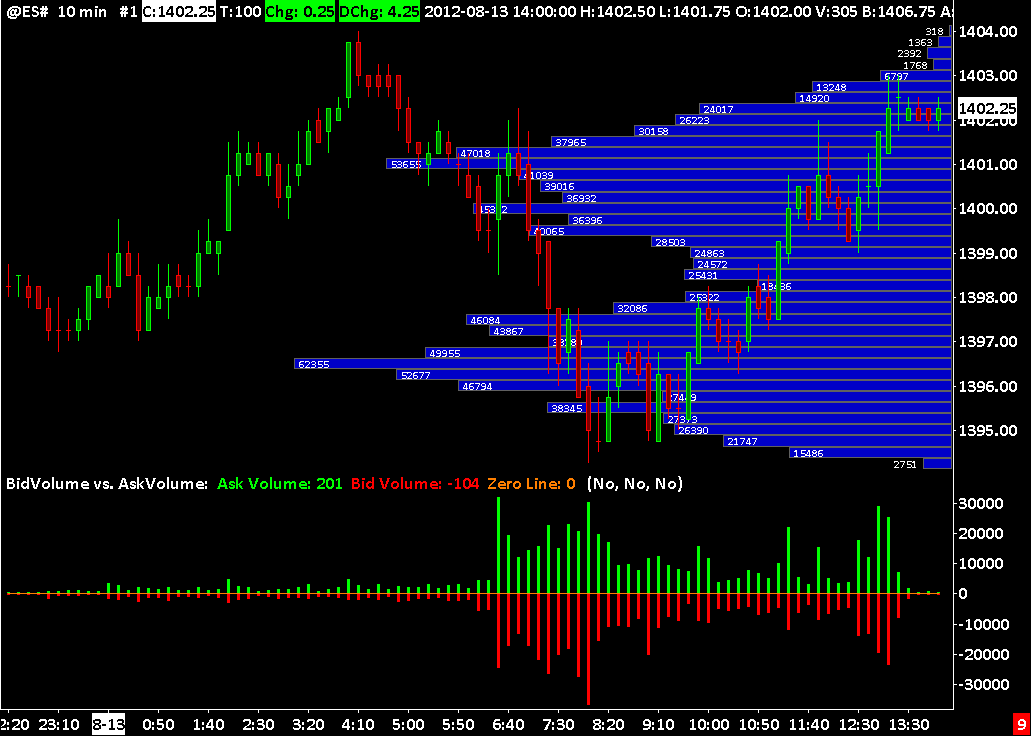

The technician believes that knowledge of a stock’s past behavior can help predict its probable future behavior. In other words, the sequence of price changes before any given day is important in predicting the price change for that day. This might be called the wallpaper principle.

Just What Exactly Is a Random Walk?

Professor Malkiel states that this topic, for many people, appears to be nonsense; that even most reader of financial pages can easily spot patterns in the market. The chart seems to display some obvious patterns. He even tries an experiment in which he asked his students to participate a pattern but then reveals that this is derived from random coin tossing. Malkiel’s class trick is to have a chart that looks like a normal stock price chart and even appears to display cycles.

The Author further discusses some tests to elaborate Technical systems more and includes in this chapter some brief details.

The Filter System

Under the popular “filter” system, a stock that has reached a low point and has moved up is said to be in an uptrend. A stock that has reached a peak and has moved down is said to be in a downtrend. This scheme is very popular with brokers, and forms of it have been recommended. This filter method is what lies behind the popular “stop-loss” order favoured by brokers.

The Dow Theory

A great tug-of-war between resistance and support. When the market tops out and moves down, that previous peak defines a resistance area, because people who missed selling at the top will be eager to do so if given another opportunity.

In the relative-strength system, an investor buys and holds those stocks that are acting well, outperforming the general market; The stocks that are poor relative to the market should be avoided or, perhaps, even sold short.

Price-volume systems suggest that when a stock rises on large or increasing volume, there is an unsatisfied excess of buying interest and the stock can be expected to continue its rise; when a stock drops in large volume, the sell signal is given. The investor following such a system is likely to be disappointed in the results.

The past history of stock prices cannot be used to predict the future in any meaningful way. Technical strategies are usually amusing, often comforting, but of no real value. This is the weak form of the random-walk theory. The most common complaint about the weakness of the random-walk theory is based on a distrust of mathematics and a misconception of what the theory means.

Another major advantage according to Professor Malkiel to a buy-and-hold strategy, is when buying and holding enable you to postpone or avoid capital gains taxes. If this buying and holding is suited to your objectives, then it will enable you to save on investment expenses, brokerage charges, and taxes, and at the same time, achieve overall performance that at least as good as that obtainable using technical methods.

Chapter 7: Fundamental Analysis is getting closer to the truth but also sucks

In this chapter, Professor Malkiel mentions how good Fundamental Analysis is through his examples and explanations. He cites two extreme views about the efficacy of fundamental analysis. The view of many is that fundamental analysis is becoming more powerful and skill-based all the time; and, an opposite-extreme view which is taken by much of the academic community that fundamental analysis gets you close to the truth but also isn’t that great either. This chapter will also recount the major battle between academics and market professionals.

Forecasting future earnings is the security analysts’ purpose. For professionals, expectation of future earnings is still the most important single factor affecting stock prices. This thinking fails in the academic world. According to them, calculations of past earnings growth are no help in predicting the future growth. If you had known the growth rates of all companies, this will not help you in predicting what growth they would achieve.

He points out that we should not take for granted the reliability and accuracy of any judge, no matter how expert they are. When one considers the low reliability of so many kinds of judgments, it does not seem too surprising that security analysts, with their particularly difficult forecasting job, should be no exception. There are four factors that Professor Malkiel mentions to help explain why security analysts have difficulty in predicting the future: The influence of random events; the creation of dubious reported earnings through creative accounting procedures; the basic incompetence of many of the analysts themselves and; the loss of the best analysts to the sales desk or to portfolio management roles.

Do Security Analysts pick winners? Professor Malkiel narrates that the real test of the analyst lies in the performance of the stocks he recommends. Analyze investment performance, not earnings forecasts.

Can any Fundamental System Pick Winners?

Can any Fundamental System Pick Winners?

Research has been done on whether above-average returns can be earned by using trading systems based on press announcements of new fundamental information and the answer, according to Professor Malkiel, seems to be clearly “Nope.” Systems are the device in which a news event such as the announcement of an unexpectedly large increase in earnings or a stock split triggers a buy signal.

Many professional investors move money from cash to equities or long-term bonds based on their forecasts of fundamental economic conditions. Several institutional investors now sell their services as asset allocators or market timers. According to Professor Malkiel, trying to do market timing is likely, not only not to add value to your investment program, but to be counterproductive.

Professor Malkiel further explains in this chapter what semi-strong and strong forms of the Random-walk Theory. He says that semi-strong form says that no published information will help the analyst to select undervalued securities while strong form says that absolutely nothing that is known or even knowable about a company will benefit the fundamental analyst.

The random-walk theory does not state that stock prices move aimlessly and erratically and are insensitive to changes in fundamental information, but on the contrary, the point of it is just the opposite: The market is so efficient prices move so quickly when new information arises that no one can buy or sell quickly enough to benefit.

Chapter 8: Modern Portfolio Theory is the latest craze and does work for some

In this chapter, Professor Malkiel narrates that a new strategy is needed, that this is the part of the book that states all about the new investment technology created within the academic world. One insight he shares is the Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) that is now widely followed on the Street since it is so basic. In this chapter, he further describes the origins and applications of Modern Portfolio theory.

Defining Risk: according to the American Heritage Dictionary, it is the possibility of suffering harm or loss. Academics have accepted the idea that risk for investors is related to the chance of disappointment in achieving expected security returns. Financial risk has generally been defined as the variance or standard deviation of returns. Professor Malkiel also specifies a simple example that will illustrate the concept of expected return and variance and how they are measured. One of the best-documented propositions in the field of finance is that, on average, investors have received higher rates of return for bearing greater risk.

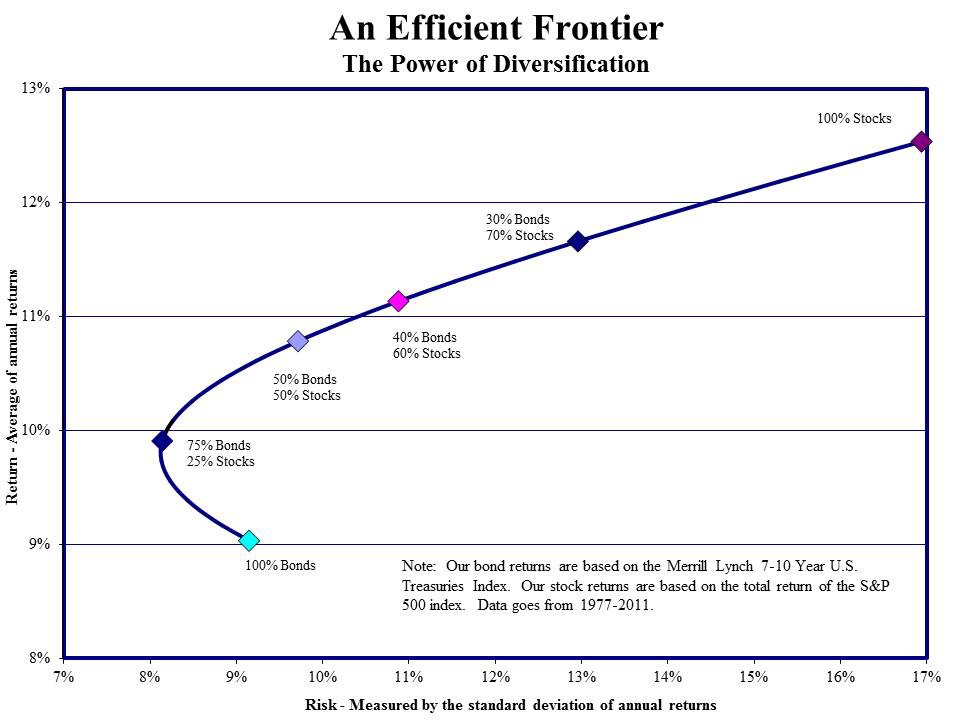

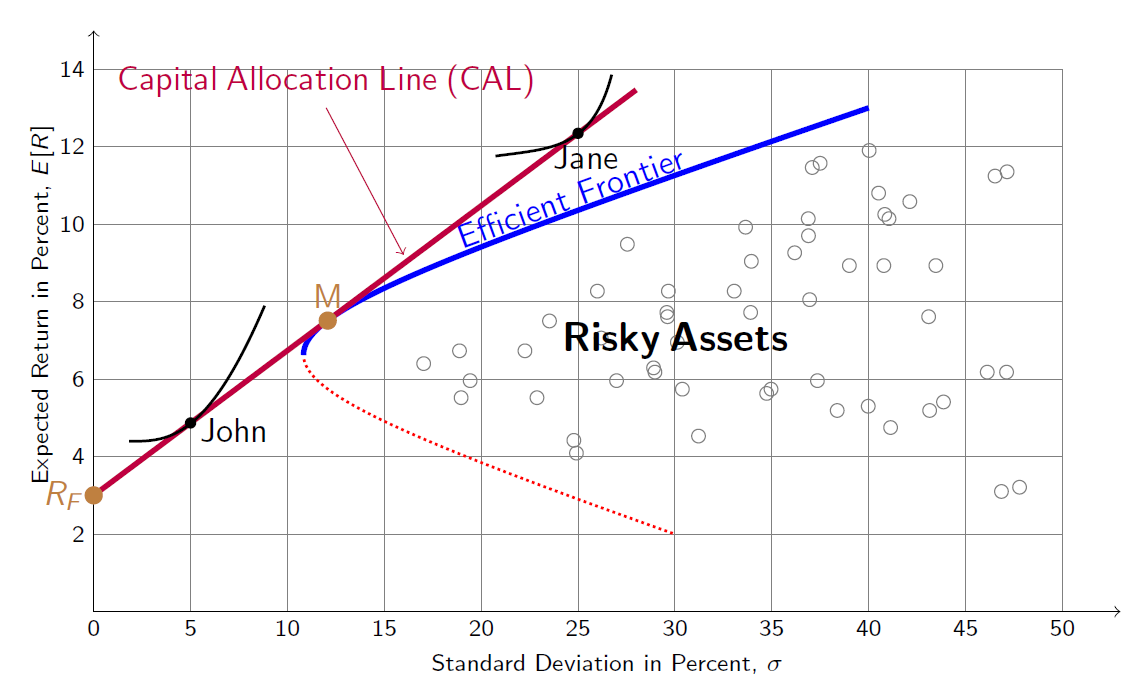

Portfolio theory begins with the assumption that all investors are risk-averse. They want high returns and guaranteed outcomes. The theory tells investors how to combine stocks in their portfolios to give them the least risk possible, consistent with the return they seek. It also gives a definite mathematical justification for the investment that is a sensible strategy for individuals who like to reduce their risks.

The theory was invented in the 1950s by Harry Markowitz. He discovered that portfolios of risky stocks might be put together in such a way that the portfolio as a whole would actually be less risky than any one of the individual stocks in it. The mathematics of modern portfolio theory is challenging; it fills the journals and, incidentally, keeps a lot of academics busy.

The theory was invented in the 1950s by Harry Markowitz. He discovered that portfolios of risky stocks might be put together in such a way that the portfolio as a whole would actually be less risky than any one of the individual stocks in it. The mathematics of modern portfolio theory is challenging; it fills the journals and, incidentally, keeps a lot of academics busy.

From the example given by the author, he finds that negative correlation is not necessary to achieve the risk reduction benefits from diversification. This correlation coefficient is used to measure the extent to which different markets hit their peaks and valleys at different times. They are the key element in Markowitz’s analysis. A perfect positive correlation indicates that two markets are in lockstep, moving up and down at precisely the same time whereas a perfect negative correlation means that two markets always move in opposite direction. According to Markowitz’s great contribution to investors’ wallets is his demonstration that anything less than perfect positive correlation can potentially reduce risk.

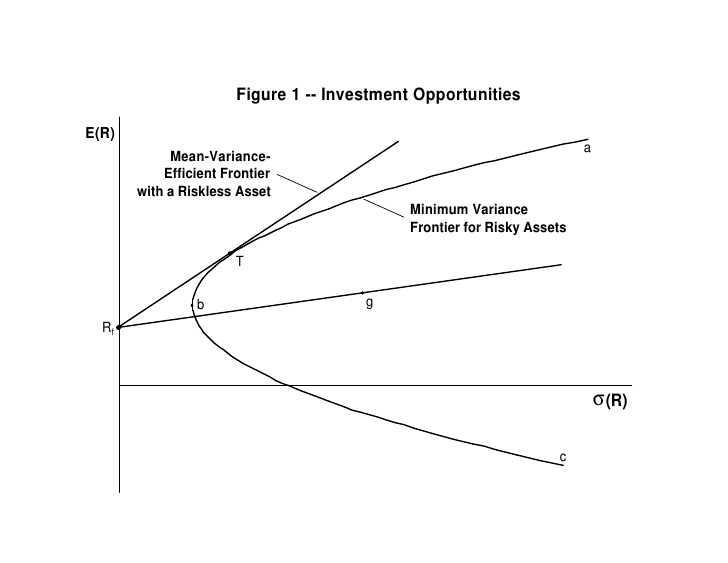

Professor Malkiel includes some charts and figures to further explain the theory or to demonstrate the point about diversification and its benefits. He further says that movements in long-term bonds do not mirror those of other assets, and long-term bonds tend to provide relatively stable returns when held to maturity. Moreover, exhibits shown in the book demonstrate that three-year correlations of real estate bonds with the market are sufficiently low to provide important diversification benefits and have shown no tendency to become less favourable over time. Professor Malkiel will further discuss portfolio theory to craft appropriate asset allocations in the succeeding chapters.

Professor Malkiel includes some charts and figures to further explain the theory or to demonstrate the point about diversification and its benefits. He further says that movements in long-term bonds do not mirror those of other assets, and long-term bonds tend to provide relatively stable returns when held to maturity. Moreover, exhibits shown in the book demonstrate that three-year correlations of real estate bonds with the market are sufficiently low to provide important diversification benefits and have shown no tendency to become less favourable over time. Professor Malkiel will further discuss portfolio theory to craft appropriate asset allocations in the succeeding chapters.

Chapter 9: How Modern Portfolio Theory works

In this chapter, Professor Malkiel begins with a refinement to modern portfolio theory citing that diversification cannot eliminate all risk because all stocks tend to move up and down together. Thus, in practice, it reduces some but not all risk. The basic logic behind the capital-asset pricing model is that there is no premium for bearing risks that can be diversified away; thus, to get a higher average long-run rate of return, you need to increase the risk level that cannot be diversified away.

Systematic risk, also called market risk, captures the reaction of individual stocks to general market swings. This is part of the total risk or variability that arises from the basic variability of stock prices in general market. The remaining variability in a stock’s returns is called unsystematic risk. Some stocks and portfolios tend to be very sensitive to market movements. This relative volatility or sensitivity to market moves can be estimated on the basis of the past record, popularly known by the Greek letter beta. Beta is based on the past however….

Systematic risk, also called market risk, captures the reaction of individual stocks to general market swings. This is part of the total risk or variability that arises from the basic variability of stock prices in general market. The remaining variability in a stock’s returns is called unsystematic risk. Some stocks and portfolios tend to be very sensitive to market movements. This relative volatility or sensitivity to market moves can be estimated on the basis of the past record, popularly known by the Greek letter beta. Beta is based on the past however….

Professor Malkiel says that what makes new investment technology different is the definition and measurement of risk. Before the capital-asset pricing model, it was believed that the return on each security was related to the total risk inherent in that security. It was believed that the return from a security varied with the instability of that security’s particular performance, with the variability or standard deviation of the returns it produced.

Professor Malkiel says that what makes new investment technology different is the definition and measurement of risk. Before the capital-asset pricing model, it was believed that the return on each security was related to the total risk inherent in that security. It was believed that the return from a security varied with the instability of that security’s particular performance, with the variability or standard deviation of the returns it produced.

The basic logic behind the capital-asset pricing model states that stocks can be combined in portfolios to eliminate specific risk, only the systematic risk will command a risk premium. Investors will not get paid for bearing risks that can be diversified away. The proof of the capital-asset pricing model can be stated as follows: If investors did get an extra return for bearing unsystematic risk, it would turn out that diversified portfolios made up of stock with large amounts of unsystematic risk would give larger returns than equally risky portfolios of stocks with less unsystematic risk.

Serious cracks in the CAPM will not lead to an abandonment of mathematical tools in financial analysis and return to traditional security analysis. There are reasons to avoid a rush to judgment: First, it is important to remember that stable returns are preferable less risky than very volatile returns; Secondly, you must keep in mind that it is very difficult to measure beta with any degree of precision and; Finally, investors should be aware that even if the long-run relationship between beta and return is flat, it can still be a useful investment management tool.

Serious cracks in the CAPM will not lead to an abandonment of mathematical tools in financial analysis and return to traditional security analysis. There are reasons to avoid a rush to judgment: First, it is important to remember that stable returns are preferable less risky than very volatile returns; Secondly, you must keep in mind that it is very difficult to measure beta with any degree of precision and; Finally, investors should be aware that even if the long-run relationship between beta and return is flat, it can still be a useful investment management tool.

If beta is badly damaged as an effective quantitative measure of risk, is there anything to take its place? Stephen Ross has developed a theory of pricing in the capital markets called arbitrage pricing theory (APT). It has a wide influence both in the academic community and in the practical world of portfolio management. To understand its logic, one must remember the correct insight underlying the CAPM.

If beta is badly damaged as an effective quantitative measure of risk, is there anything to take its place? Stephen Ross has developed a theory of pricing in the capital markets called arbitrage pricing theory (APT). It has a wide influence both in the academic community and in the practical world of portfolio management. To understand its logic, one must remember the correct insight underlying the CAPM.

The only risk that investors should be compensated for bearing is the risk that cannot be diversified away. Only systematic risk will command a risk premium in the market. It appears that several other systematic risk measures affect the valuation of securities.

Chapter 10: The Market is Efficient with Pockets of Inefficiency

This chapter will tackle the attempts to show that the market is not efficient and that there is no such thing as a profitable random walk through Wall Street. Professor Malkiel reviews all the recent research proclaiming the demise of the efficient-market theory; EMT after all implies that market prices are unpredictable but hyper efficient in correcting itself. He concludes that obituaries are greatly exaggerated and the extent to which the stock market is usefully predictable has been vastly overstated.

Recall that the weak form of the efficient-market hypothesis says simply that the technical analysis of past price patterns to forecast the future is useless because any information from such an analysis will already have been incorporated in current market prices.

A random walk would characterize a price series where all subsequent price changes represent random departures from previous prices. This model states that investment returns are serially independent of each-other and that their probability distributions are constant through time. More recent work, however, indicated that the random-walk model does not strictly hold. Some consistent patterns of correlations, inconsistent with the model, have been uncovered. It is less clear that violations exist of the weak form of the efficient-market hypothesis, which states only that unexploited trading opportunities should not persist in any efficient market. (1) Stocks do sometimes get on one-way streets; (2) But eventually stock prices do change direction and hence stockholder returns tend to reverse themselves; (3) Stocks are subject to seasonal moodiness, especially at the beginning of the year and the end of the week.

Academics and financial analysts in the semi-strong school of market efficiency believe that all public information about a company is always reflected in the stock’s price. They are skeptical about the ability of fundamental security analysts to pore over data concerning a company’s earnings and dividends in an effort to find undervalued stocks, which represent good value for investors. Professor Malkiel cites some qualifications of value techniques: look for securities that (1) are relatively small, smaller is often better; (2) sell at low multiples compared with their earnings; (3) have low prices relative to the value of their assets, and; (4) have high dividends compared with their market prices.

Dogs of the Dow strategy is an interesting strategy that became popular in the mid-1990s. This is to combine some of the value patterns with a general contrarian style of investing consistent with the idea that out-of-favor stocks eventually tend to reverse direction.

Concluding comment of Professor Malkiel: market valuations rest on both logical and psychological factors. The theory of valuation depends on the projection of a long-term stream of dividends whose growth rate is extraordinarily difficult to estimate. Thus, fundamental value is never a definite number. It is a band of possible values, and prices can move sharply within this band whenever there is increased uncertainty. The appropriate risk premiums for common equities are changeable and far from obvious either to investors or to economists. There is room for the hopes, fears, and favorite fashions of market participants to play a role in the valuation process.

Chapter 11: How to Walk down Wall Street now that you know it is random

Part four of the book explains how-to-do-it guide for your random walk down Wall Street. In this chapter, Professor Malkiel offers general investment advice that should be useful to all investors, even if they don’t believe that security markets are highly efficient. He also says that you can take your random walk only after you have made detailed and careful plans with regard to all your investments, including your cash reserves. Think of the advice that follows a set of warm-up exercises that will enable you to reduce your income taxes and risk, at the same time increase your returns.

Part four of the book explains how-to-do-it guide for your random walk down Wall Street. In this chapter, Professor Malkiel offers general investment advice that should be useful to all investors, even if they don’t believe that security markets are highly efficient. He also says that you can take your random walk only after you have made detailed and careful plans with regard to all your investments, including your cash reserves. Think of the advice that follows a set of warm-up exercises that will enable you to reduce your income taxes and risk, at the same time increase your returns.

Exercise 1: Cover Thyself with Protection

Exercise 1: Cover Thyself with Protection

Patience is key element in investing; you can’t afford to pull your money out at the wrong time. You need staying power to increase your earning attractive long-run returns. That’s why it is important to have non-investment resources to draw on should any emergency strike you or your family.

Exercise 2: Know your Investment

Exercise 2: Know your Investment

Determining clear goals is a part of investment process with disastrous results. You must decide what degree of risk you are willing to assume and what kinds of investments are most suitable to your tax bracket.

Exercise 3: Dodge Uncle Sam Whenever You Can

Exercise 3: Dodge Uncle Sam Whenever You Can

One of the best ways to obtain extra investment funds is to avoid taxes legally. Professor Malkiel says that there are no income taxes on money invested in a retirement plan until you actually retire and use the money. Professor Malkiel cites some plans to give some examples.

Exercise 4: Be Competitive; Let the Yield on your Cash Reserve Keep Pace with Inflation

Exercise 4: Be Competitive; Let the Yield on your Cash Reserve Keep Pace with Inflation

As Professor Malkiel mentions, some of the ready assets are necessary for pending expenses. There are four short-term investment instruments he points out that can at least help stand up to inflation. These are (1) money-market mutual funds; (2) money-market deposit accounts; (3) bank certificates; and (4) tax-exempt money-market funds.

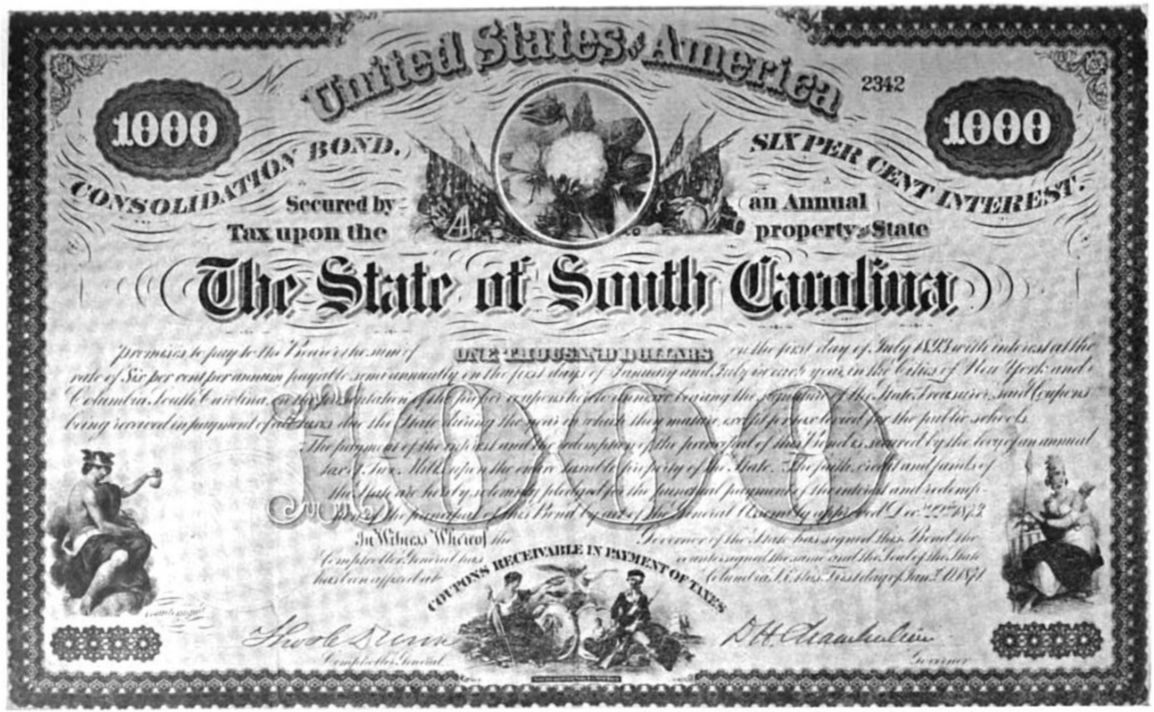

Exercise 5: Investigate a Promenade through Bond Country

Exercise 5: Investigate a Promenade through Bond Country

In this particular topic, Professor Malkiel mentions four kinds of bond purchases according to his view: (1) zero-coupon bonds, (2) bond mutual funds, (3) tax-exempt bonds and bond funds, and (4) U.S. Treasury inflation-protection securities.

Exercise 6: Begin Your Walk at Your Own Home; Renting Leads to Flabby Investment Muscles

Exercise 6: Begin Your Walk at Your Own Home; Renting Leads to Flabby Investment Muscles

The natural real estate investment for most people is the single-family home or the condominium. They are encouraging home ownership and cites two important tax breaks: (1) Although rent is not deductible from income taxes, the two major expenses associated with homeownership-interest payments on your mortgage and property taxes are fully deductible; (2) realized gains in the value of your house that are tax exempt. In addition, ownership of a house is a good way to force yourself to save, and a house provides emotional satisfaction.

Exercise 7: Beef Up with Real Estate Investment Trusts

The packaging of ownership interests in real property into trusts called Real Estate Investment. This REITs are like any other common stock and are actively traded on the major stock exchanges.

Professor Malkiel further cites additional Exercises which are: (8) Tiptoe through the investment fields of gold and collectibles; (9) Remember the investment fields of gold and collectibles; and (10) diversify your investment steps. These exercises have been subject to a final checkup that you should do.

Chapter 12: Macro-Economic considerations are important for investors

This chapter is where you will learn how to become a financial bookie, according to Professor Malkiel. This is an important chapter because the money you are betting is your own.

Very long-run returns from common stocks are driven by two critical factors: the dividend yield at the time of purchase, and the future growth rate of the dividends. In principle, for the buyer who holds his stocks forever is worth the present or discounted value of its stream of future dividends. The discounted value of the stream of dividends can be shown with a very simple formula for long-run total return for either an individual stock or the market as a whole: long-run equity return = initial dividend yield + growth rate of dividends.

Very long-run returns from common stocks are driven by two critical factors: the dividend yield at the time of purchase, and the future growth rate of the dividends. In principle, for the buyer who holds his stocks forever is worth the present or discounted value of its stream of future dividends. The discounted value of the stream of dividends can be shown with a very simple formula for long-run total return for either an individual stock or the market as a whole: long-run equity return = initial dividend yield + growth rate of dividends.

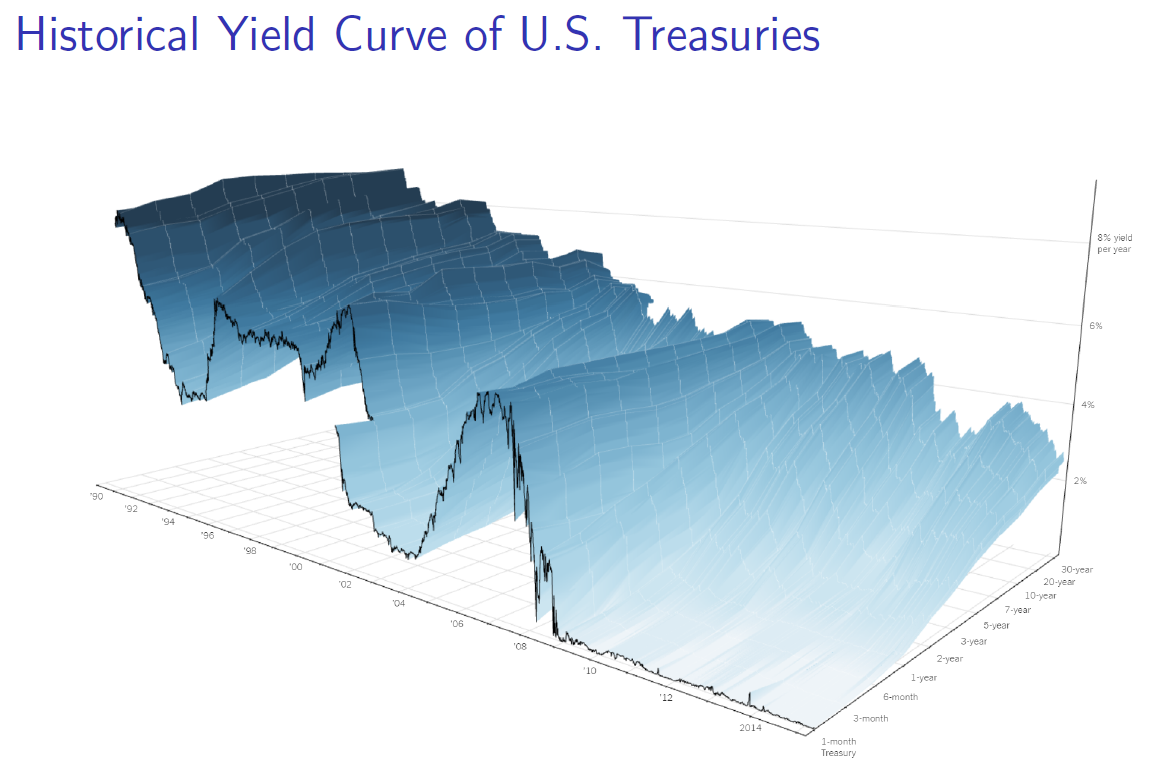

There are three eras of financial market returns Professor Malkiel discusses: Era I, the age of comfort, which covers the years of growth after World War II. Stockholders made out extremely well after inflation, whereas the meager returns earned by bondholders were substantially below the average inflation rate. Era II, the Age of Angst: widespread rebellion by millions of teenagers produced during the baby boom, economic, and political instability created by the Vietnam War. No one was exempt: neither stocks nor bonds. Era III, the Age of Exuberance is when the boomers matured, peace reigned, and a non-inflationary prosperity set in. It was a golden age for stockholders and bondholders.

There are three eras of financial market returns Professor Malkiel discusses: Era I, the age of comfort, which covers the years of growth after World War II. Stockholders made out extremely well after inflation, whereas the meager returns earned by bondholders were substantially below the average inflation rate. Era II, the Age of Angst: widespread rebellion by millions of teenagers produced during the baby boom, economic, and political instability created by the Vietnam War. No one was exempt: neither stocks nor bonds. Era III, the Age of Exuberance is when the boomers matured, peace reigned, and a non-inflationary prosperity set in. It was a golden age for stockholders and bondholders.

The Age of the Millennium

Although Professor Malkiel states that he remains convinced that no one can predict short-term movements in securities markets, he does believe it is possible to estimate the likely range of long-run rates of return investors can expect from financial assets. It seems very clear that it would be unrealistic to anticipate that the generous double-digit returns earned by stock and bond investors during the 1980s and 1990s can be expected to continue in the early decades of the twenty-first century. Looking first at the bond market, we can get a very good idea of the returns that will be gained by long-term holders. Holders of good quality corporate bonds will earn if the bonds are held to maturity. Holders of long-term zero-coupon Treasury bonds will earn until maturity and so on.

He even is skeptical that anyone can predict the course of short-term stock price movements, and perhaps better off for it. He even shares his one favorite episodes from I Love a Mystery wherein this is about a greedy stock-market investor who wished that just once he would be allowed to see the paper, with its stock price changes, twenty-four hours in advance.

We can employ the same methods used in Chapter Twelve for the market as a whole to project the long-run rates of return for individual stocks, where it is reasonable to project a modest rate of growth over an extended period. Again, he suggests to only use the first two determinants in the analysis. He estimates the rate of return on an individual stock by adding the initial dividend yield to the expected growth rate of earnings. Although P/E ratios are obviously very important in explaining returns in the short run, such valuation changes are less important over the very long run and are unpredictable in any event.

Chapter 13: You can eat well or sleep well, it’s up to you

This chapter tackles a life-cycle guide to investing. Professor Malkiel even cites that it is simple to say that a thirty-four-year-old and a sixty-four-year-old saving for retirement may cautiously use different financial instruments to accomplish their goals. The thirty-four-year-old just beginning to enter the peak years of salaried earnings that can use wages to cover any losses from increased risk and the sixty-four-year-old does not have the long-term luxury of relying on salary income and cannot afford to lose money that will be needed in the near future.

In essence, these strategic considerations have to do with a person’s capacity for risk. Most of the discussion about risk has dealt with one’s attitude toward risk. Although both of them may invest in a certificate of deposit, the younger will do so because of an attitudinal aversion to risk and the older because of the reduced capacity to accept the risk. The most important investment decision you will probably ever make concerns the balancing of asset categories at different stages of your life.

There are key principles to determine a rational basis for making asset-allocation decisions:

- History shows that risk and return are related.

- The risk of investing in common stocks and bonds depends on the length of time the investments are held. The longer an investor’s holding period, the lower the risk.

- Dollar-cost averaging can be a useful, though controversial, technique to reduce the risk of stock and bond investment.

- You must distinguish between your attitude toward and your capacity for risk.

The risks you can afford to take depend on your total financial situation, including the types and sources of your income exclusive of investment income.

In this section contains reviews of three broad guidelines that will help an investment plan to particular circumstances:

In this section contains reviews of three broad guidelines that will help an investment plan to particular circumstances:

- Specific Needs Require Dedicated Specific Assets:

Always keep in mind – a specific need must be funded with specific assets dedicated to that need.

- Recognize Your Tolerance for Risk:

The biggest adjustment to the general guidelines concerns your own attitude toward risk. It is for this reason that successful financial planning is more of an art than a science. General guidelines can be extremely helpful in determining what proportion of a person’s funds should be deployed among different asset categories. Risk tolerance is an essential aspect of any financial plan and only you can evaluate your attitude toward risk.

And lastly:

- Persistent Savings in Regular Amounts, No Matter How Small, Pays Off.

Professor Malkiel shares advice from Talmud Rabbi Isaac saying that one should always divide his wealth into three parts: a third in land, a third in merchandise or business, and a third ready-at-hand. Such an asset allocation is hardly unreasonable but can improve this advice because we have more refined instruments and a greater appreciation of the considerations that make different asset allocations appropriate for different people.

As investors age, they should start cutting back on riskier investments and start increasing the proportion of the portfolio committed to bonds and stocks that pay generous dividends such as REITs.

For most people, Professor Malkiel recommends funds rather than individual stocks for portfolio formation. He cites two reasons for this. First, most people do not have sufficient capital to diversify properly; and Secondly, he recognizes that most younger people will not have substantial assets and will be accumulating portfolios by monthly investments.

Chapter 14: Investing advice now that your get Malkiel’s book

This chapter offers rules for buying stocks and specific recommendations for the instruments you can use to follow the asset allocation guidelines presented in Chapter Thirteen. By now, you have made sensible decisions on taxes, housing, insurance, and how to get the most out of your cash reserves. You also have reviewed your objectives, your stage in the life cycle, and your attitude toward risk and decided how much of your assets to put into the stock market.

In the first case, you simply buy shares in various index funds designed to track the different classes of stocks that make up your portfolio. This method also has the virtue of being simple. Under the second system, you jog down Wall Street, picking your own stocks and getting in comparison with the yield obtained with index funds much higher or much lower rates of return; and third, you can sit on a curb and choose a professional investment manager to do the walking down Wall Street for you.

Index funds trade only when necessary, whereas active funds typically have a turnover rate close to 100 percent, and often even more. Index funds are also tax-friendly. It is also relatively predictable. It is fully invested. And finally, it is easier to evaluate. With index funds, you know exactly what you are getting, and investment process is made incredibly simple.

Index funds trade only when necessary, whereas active funds typically have a turnover rate close to 100 percent, and often even more. Index funds are also tax-friendly. It is also relatively predictable. It is fully invested. And finally, it is easier to evaluate. With index funds, you know exactly what you are getting, and investment process is made incredibly simple.

The indexing strategy is one that Professor Malkiel recommended even before index funds exist. It is clearly an idea whose time had come. Although he recommends indexing or so-called passive investing, there are valid criticisms of too narrow a definition of indexing.

One of the advantages of passive portfolio management is that such a strategy minimizes transactions costs as well as taxes. To a considerable extent, index mutual funds help solve the tax problem. The do not trade from security to security and, thus, they tend to avoid capital gains taxes.

The fund is able to defer capital gains by the following techniques: First, the portfolio is indexed to the S&P 500 so there is no active management that tends to realize gains; Second, when securities do have to be sold, the fund sells the highest-cost securities first; Third, the funds offsets unavoidable gains by judiciously selling other securities on which there is a loss. As a result, the fund may not perfectly track the benchmark index, but it should come very close.

In this chapter, Professor Malkiel further states four rules for successful stock selection:

- Rule 1: Confine stock purchases to companies that appear able to sustain above-average earnings growth for at least five years.

- Rule 2: Never pay more for a stock than can reasonably be justified by a firm foundation of value.

- Rule 3: It helps to buy stocks with the kinds of stories of anticipated growth on which investors can build castles in the air.

- Rule 4: Trade a little as possible.

Investing is a bit like lovemaking, according to Professor Malkiel. Ultimately, it is really an art requiring a certain talent and the presence of a mysterious force called luck. If you have the talent to recognize stocks that have good value, and the art to recognize a story that will catch the fancy of others, it’s a great feeling to see the market vindicate you. If you are not so lucky, limit your risks and avoid much of the pain that sometimes involved in the playing.