The Misguided Conservative Ideal: R.B. Bennett and the Western Canadian Reaction between 1930-1935.

A fair amount of a party’s political success relies on good fortune. Steve Martin the comedian famously that ti……ming….is everything. If this is the case, R.B. Bennett was the most unfortunate Prime Minister in Canadian history. This essay will re-evaluate the Conservative party’s response to the Great Depression in Western Canada, accomplishing four objectives in order to defend Bennett[1]. First, it will outline R.B. Bennett’s adherence to Liberal capitalist order. Second, this essay will assess the Conservative party’s response to the agricultural crisis in the Canadian West. Thirdly, it will analyze their misfortunes in the West and the public response to the Conservative efforts. Finally, it will conclude that international economic stagnation, Western agricultural failure, philosophical discord inevitably led to Bennett becoming a victim of political circumstance. Hence politics is high risk, so one should try to start a term in leadership when the economy is expected to grow.

A fair amount of a party’s political success relies on good fortune. Steve Martin the comedian famously that ti……ming….is everything. If this is the case, R.B. Bennett was the most unfortunate Prime Minister in Canadian history. This essay will re-evaluate the Conservative party’s response to the Great Depression in Western Canada, accomplishing four objectives in order to defend Bennett[1]. First, it will outline R.B. Bennett’s adherence to Liberal capitalist order. Second, this essay will assess the Conservative party’s response to the agricultural crisis in the Canadian West. Thirdly, it will analyze their misfortunes in the West and the public response to the Conservative efforts. Finally, it will conclude that international economic stagnation, Western agricultural failure, philosophical discord inevitably led to Bennett becoming a victim of political circumstance. Hence politics is high risk, so one should try to start a term in leadership when the economy is expected to grow.

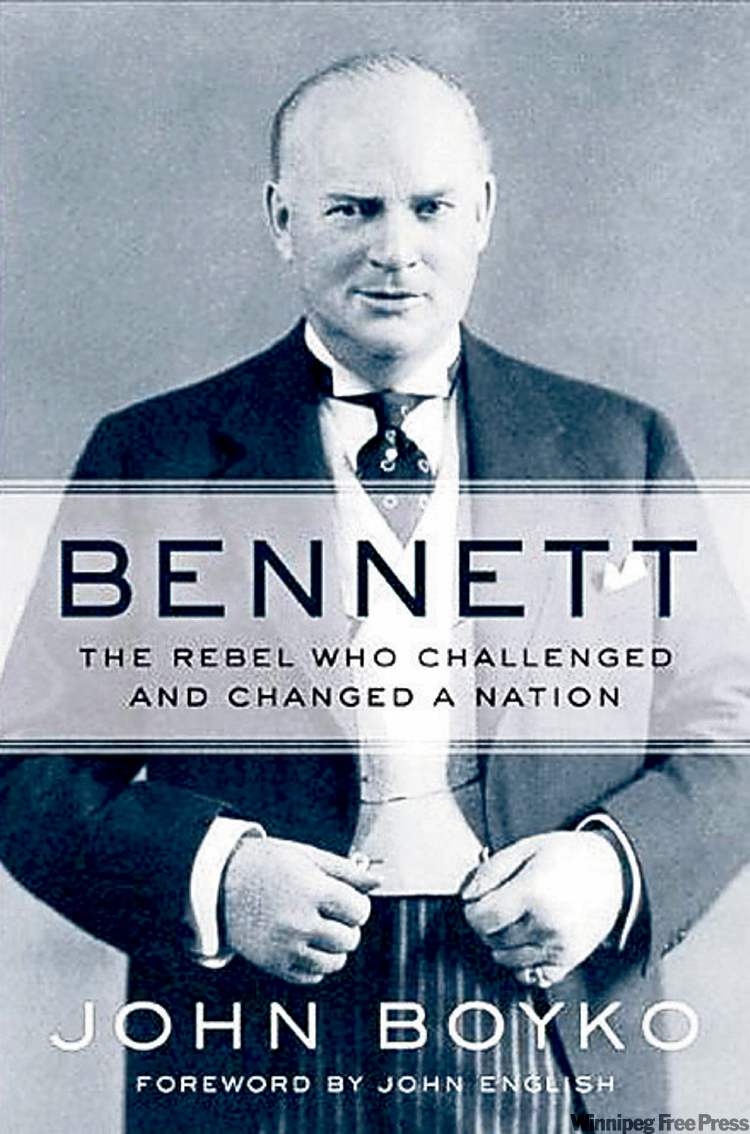

The tragedy of Richard Bedford Bennett is rooted in a political philosophy that was no longer sustainable in the 1930s: the Liberal capitalist order. According to Ian Mackay, the classical liberal model was “hegemonic in Canada from the mid-nineteenth century to the 1940s”[2]. Unfetter laissez-capitalism was prominent internationally and its philosophy of individualism had a significant influence in the Conservative party of Canada and on its 8th leader. Bennett advocated small-government principles in an era were these ideals were most acceptable to the Canadian public, particularly in Western Canada. The child of a staunch Methodist mother, Bennett developed a strong Protestant work ethic [3] and through the help friend Max Aitken, Bennett became a Western millionaire lawyer espousing the virtues of liberal capitalist order. As a Conservative House of Commons representative for Calgary, Alberta, R.B. Bennett “thought of himself as Calgarian. It was his home; it was where he had made his way in the world”[4]. Eventually, being a convenient candidate, the Conservative party found both his ideology and his allegiance to the West strategically appealing choosing Bennett as their leader at the 1927 Convention[5].

The tragedy of Richard Bedford Bennett is rooted in a political philosophy that was no longer sustainable in the 1930s: the Liberal capitalist order. According to Ian Mackay, the classical liberal model was “hegemonic in Canada from the mid-nineteenth century to the 1940s”[2]. Unfetter laissez-capitalism was prominent internationally and its philosophy of individualism had a significant influence in the Conservative party of Canada and on its 8th leader. Bennett advocated small-government principles in an era were these ideals were most acceptable to the Canadian public, particularly in Western Canada. The child of a staunch Methodist mother, Bennett developed a strong Protestant work ethic [3] and through the help friend Max Aitken, Bennett became a Western millionaire lawyer espousing the virtues of liberal capitalist order. As a Conservative House of Commons representative for Calgary, Alberta, R.B. Bennett “thought of himself as Calgarian. It was his home; it was where he had made his way in the world”[4]. Eventually, being a convenient candidate, the Conservative party found both his ideology and his allegiance to the West strategically appealing choosing Bennett as their leader at the 1927 Convention[5].

The Great Depression of the 1930s transformed unemployment into the single most challenging threat to the liberal order. Throughout the 1920s, the urbanization process continued across Canada while in the Prairie West, agricultural expansion continued unabated. According to Struthers, “until the development of the Canadian West as a major wheat-producing region between 1896 and 1930, few economic links existed to bind the diverse regions of Canada together”[6]. The Palliser Triangle represented potential prosperity for the impoverished European family and despite the economic imperialism of the east and several minor depressions, their desire for self-sustaining autonomy had been realized. Unfortunately, the Great Depression hit Western Canada the hardest.

The Great Depression of the 1930s transformed unemployment into the single most challenging threat to the liberal order. Throughout the 1920s, the urbanization process continued across Canada while in the Prairie West, agricultural expansion continued unabated. According to Struthers, “until the development of the Canadian West as a major wheat-producing region between 1896 and 1930, few economic links existed to bind the diverse regions of Canada together”[6]. The Palliser Triangle represented potential prosperity for the impoverished European family and despite the economic imperialism of the east and several minor depressions, their desire for self-sustaining autonomy had been realized. Unfortunately, the Great Depression hit Western Canada the hardest.

An unprecedented catastrophe occurred as two events crippled Western Canadian prosperity. The first event was the global phenomenon triggered by the US stock market crash of October 29th, 1929. The result locally was that the price of wheat fell 40 per cent on the price index while overproduction of wheat exacerbated the crisis[7]. The second event was environmental crisis that curbed agriculture further. Drought caused by change in wind interactions between the Gulf of Mexico and Pacific streams, and imprudent cultivation practices, localized in Western Canada, meant that the soil could literally blow away (Seager, Watkins, Struthers). Compared to other constituents, “the plight of farmer in western Canada was rather worse. Canada’s backbone, the prairies, was broken, not by the depression alone, but by depression and drought”[8].

An unprecedented catastrophe occurred as two events crippled Western Canadian prosperity. The first event was the global phenomenon triggered by the US stock market crash of October 29th, 1929. The result locally was that the price of wheat fell 40 per cent on the price index while overproduction of wheat exacerbated the crisis[7]. The second event was environmental crisis that curbed agriculture further. Drought caused by change in wind interactions between the Gulf of Mexico and Pacific streams, and imprudent cultivation practices, localized in Western Canada, meant that the soil could literally blow away (Seager, Watkins, Struthers). Compared to other constituents, “the plight of farmer in western Canada was rather worse. Canada’s backbone, the prairies, was broken, not by the depression alone, but by depression and drought”[8].

Enter the new Western Conservative leader R.B. Bennett in the 1930 federal election. Unemployment proved to be decisive in the election campaign, most of which was confined to the drought stricken western provinces. Liberal leader Mackenzie King’s electoral strategy was to deflect responsibility onto western provincial jurisdictions under section 92 of the BNA Act making him seem “quite removed from the economic calamity that was beginning to preoccupy Canadians”[9]. Conversely, R.B. Bennett’s Western campaign promised to “initiate whatever action is necessary…or perish in the attempt”[10] and to use grain tariffs “to blast a way into the markets that have been closed to you”[11]. The Conservative party gained a sound majority government.

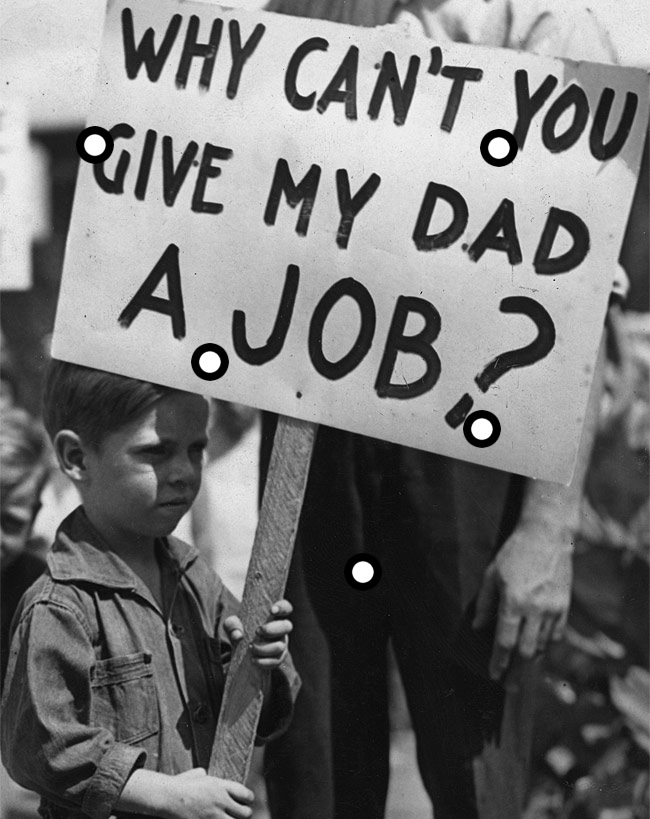

R.B. Bennett’s new 1930 mandate hinged on his solution to the unemployment crisis which was looming over Western Canada and expectations were high. Unfortunately, the drought proved to be a serious liability for Bennett’s economic recovery plans. His pro-business, anti-interventionist inclinations provided little assurance to the millions of unemployed who were becoming increasingly desperate and agitating for change. According to Struthers, “the Tory leader was convinced that the present depression was a passing, mostly seasonal phenomenon”[12]. He was patently wrong. To be fair, many other countries adhering to liberal capitalist order did not believe the crisis would last for long either[13]. As a consequence of this trust in past precedent, the Conservative solution was based in short-term policy implementation rather than long term initiatives that would conflict with the notion of balanced budgets and laissez-faire.

R.B. Bennett’s new 1930 mandate hinged on his solution to the unemployment crisis which was looming over Western Canada and expectations were high. Unfortunately, the drought proved to be a serious liability for Bennett’s economic recovery plans. His pro-business, anti-interventionist inclinations provided little assurance to the millions of unemployed who were becoming increasingly desperate and agitating for change. According to Struthers, “the Tory leader was convinced that the present depression was a passing, mostly seasonal phenomenon”[12]. He was patently wrong. To be fair, many other countries adhering to liberal capitalist order did not believe the crisis would last for long either[13]. As a consequence of this trust in past precedent, the Conservative solution was based in short-term policy implementation rather than long term initiatives that would conflict with the notion of balanced budgets and laissez-faire.

The capitalist philosophical crisis haunted Bennett. There was philosophical discord in Bennett’s party between Liberal capitalism and extensive government interventionism, so R.B. Bennett “who was [posturing] a radical change in government policy to ensure prosperity”[14] but merely implemented minor relief plans that did not engage the federal government substantially in provincial jurisdiction. The Conservatives established the 1930 Relief Act, which relied on municipal and provincial funding for implementation with a federal expenditure of 28 million[15]. It was doomed to failure. Unfortunately, “Bennett had no way of ensuring that the money was fairly and wisely spent”[16] and there was a general lack of finances on the other levels of government regardless. By 1931, Bennett governed under the Statute of Westminster but such monumental achievements[17] were overshadowed by the economic situation, which was still gradually deteriorating most significantly due to the devastation of the prairie wheat crisis shared only by the American west[18]. “The price collapse of 1930 had beggared many wheat farmers, and a spring drought meant that there would be no 1931 crop at all in some areas”[19]. With the wheat economy bust, 54 per cent of the nation’s population worked in towns and cities, and urban issues like old-age pensions were the most pressing of the day[20].

The capitalist philosophical crisis haunted Bennett. There was philosophical discord in Bennett’s party between Liberal capitalism and extensive government interventionism, so R.B. Bennett “who was [posturing] a radical change in government policy to ensure prosperity”[14] but merely implemented minor relief plans that did not engage the federal government substantially in provincial jurisdiction. The Conservatives established the 1930 Relief Act, which relied on municipal and provincial funding for implementation with a federal expenditure of 28 million[15]. It was doomed to failure. Unfortunately, “Bennett had no way of ensuring that the money was fairly and wisely spent”[16] and there was a general lack of finances on the other levels of government regardless. By 1931, Bennett governed under the Statute of Westminster but such monumental achievements[17] were overshadowed by the economic situation, which was still gradually deteriorating most significantly due to the devastation of the prairie wheat crisis shared only by the American west[18]. “The price collapse of 1930 had beggared many wheat farmers, and a spring drought meant that there would be no 1931 crop at all in some areas”[19]. With the wheat economy bust, 54 per cent of the nation’s population worked in towns and cities, and urban issues like old-age pensions were the most pressing of the day[20].

After the collapse of Bennett’s unemployment relief efforts in the spring of 1932, he commissioned social worker Charlotte Whitton to write a two-hundred-page report on the Western crisis that was the growing liability on his government. As the director of the Canadian Council on Child Welfare, Whitton’s the most astonishing revelation was the argument that almost “40 percent of those then receiving relief in the West did not really need it…” adding that “…the plight of the people was pitiful but it was ‘not one deriving from the present emergency’ and therefore should not be supported by federal relief”[21]. The 100,000 transients in the West, she warned Bennett, were “getting out of hand” [22] and called for more social workers like her for the relief effort. This is exactly what Bennett wanted to hear since he maintained the liberal order “attribut[ing] the social turmoil not to hard times, but to foreign agitators and communist sympathizers.”[23] Whitton served to confirm, in Bennett’s mind, that the distinction between lethargic and desperate unemployed was distorted and that there was widespread abuse in the relief system. Having ignored the finer points of Whitton’s solution, Bennett established a direct relief method for the transients beyond the creation of paved roads that characterized his previous Relief Act.

After the collapse of Bennett’s unemployment relief efforts in the spring of 1932, he commissioned social worker Charlotte Whitton to write a two-hundred-page report on the Western crisis that was the growing liability on his government. As the director of the Canadian Council on Child Welfare, Whitton’s the most astonishing revelation was the argument that almost “40 percent of those then receiving relief in the West did not really need it…” adding that “…the plight of the people was pitiful but it was ‘not one deriving from the present emergency’ and therefore should not be supported by federal relief”[21]. The 100,000 transients in the West, she warned Bennett, were “getting out of hand” [22] and called for more social workers like her for the relief effort. This is exactly what Bennett wanted to hear since he maintained the liberal order “attribut[ing] the social turmoil not to hard times, but to foreign agitators and communist sympathizers.”[23] Whitton served to confirm, in Bennett’s mind, that the distinction between lethargic and desperate unemployed was distorted and that there was widespread abuse in the relief system. Having ignored the finer points of Whitton’s solution, Bennett established a direct relief method for the transients beyond the creation of paved roads that characterized his previous Relief Act.

As Conservative party strategy, transients could provide the focal point for the Western crisis. Bennett’s ideology suggested that the urbanization of transients was pejorative, he feared that “peace, order, and government would be disrupted by a Soviet-style revolution”[24]. Knowing the rural life well, Bennett believed that the people should be forced ‘back to the land’[25]. As a solution, Army General Andrew McNaughton’s proposed a scheme called PC 2248. He argued that “by taking the men out of the conditions of misery in the cities and giving them a reasonable standard of living and comfort,” McNaughton explained persuasively, “…the government would be ‘removing the active elements on which ‘Red’ agitator could play’[26]. Removing transients from urban centres would mean the crisis could be over or at least less visible.

By late 1932, relief camps for single, unemployed males administered by the Department of National Defense were being established to extract transients from urban centres where political turmoil could ensue[27]. Even in a public speech, Bennett asked “every man and woman to put the iron heel of ruthlessness against”[28] emerging political challenges to the Liberal order. With the plan underway, the RCMP began removing transients from the trains in Western Canada and relocating them in work camps outside of urban centres. Bennett’s obsession with balanced budget, social order from civil unrest particularly Western Canada’s third party challenges was Bennett’s pre-occupation from 1931 to 1933[29]. The bulk of the Conservative election platform has been converted into policy by the summer of 1932”[30]. Imperial economic conference of 1932 failed to solve the problem of Great Depression highlighting the unavoidable impact of global economic collapse[31]. The ‘Bennett Buggies’ having been entrenched as a sarcastic criticism of the state of affairs.

By late 1932, relief camps for single, unemployed males administered by the Department of National Defense were being established to extract transients from urban centres where political turmoil could ensue[27]. Even in a public speech, Bennett asked “every man and woman to put the iron heel of ruthlessness against”[28] emerging political challenges to the Liberal order. With the plan underway, the RCMP began removing transients from the trains in Western Canada and relocating them in work camps outside of urban centres. Bennett’s obsession with balanced budget, social order from civil unrest particularly Western Canada’s third party challenges was Bennett’s pre-occupation from 1931 to 1933[29]. The bulk of the Conservative election platform has been converted into policy by the summer of 1932”[30]. Imperial economic conference of 1932 failed to solve the problem of Great Depression highlighting the unavoidable impact of global economic collapse[31]. The ‘Bennett Buggies’ having been entrenched as a sarcastic criticism of the state of affairs.

In January 1933, Bennett added to his administrative blunders when the Western provincial leaders asked that the federal government to be entirely financially responsible for direct relief[32]. Bennett’s frustrated response failed to mitigate deep resentment from western premiers, like Pattulo of BC and Gardiner of Saskatchewan, when he attacked them for fiscal ‘extravagance’ and suggested that “the Prairie Provinces give up old age pensions, telephones, and electrical service to ‘maintain the financial integrity of the nation’”[33]. Fiscal concerns of Bennett were calling for the burdensome western provinces to deliver balanced budgets. Ultimately, Bennett had to pick up the slack of their supposed incompetence. Bennett was not interested in spending money Canada’s government didn’t have. “It was no wonder that a discouraged R.B. Bennett talked openly of retirement in the fall of 1933”[34]. He and his Conservative party rejected full-scale state intervention as long as feasibly possible. Reform was now crucial.

By 1935, there were more than two hundred camps in the system serving mostly Western Canada. Regardless of the historian’s political leanings, their description and analysis of these camps is resoundingly negative. According to Wilbury’s account, those on relief were “inmates of the government labor camps”[35] casting a grim light on Bennett’s failed solution which may have exacerbated the problem. According to Struthers, “the Department of National Defence relief camps represent one of the most tragic and puzzling episodes of the Depression in Canada”[36] and would be Bennett’s greatest blunder. “The camps soon became a liability, though, disliked by the unemployed, labour unions and the general public”[37]. Unfortunately for Bennett, the military styled DND camps would be referred to as ‘slave camps’ that “symbolized everything wrong with Bennett’s approach to the depression and eventually provoked the most violent episode of the decade”[38]. Struthers is referring to the scathing actions of Bennett in regard to the Regina Riot.

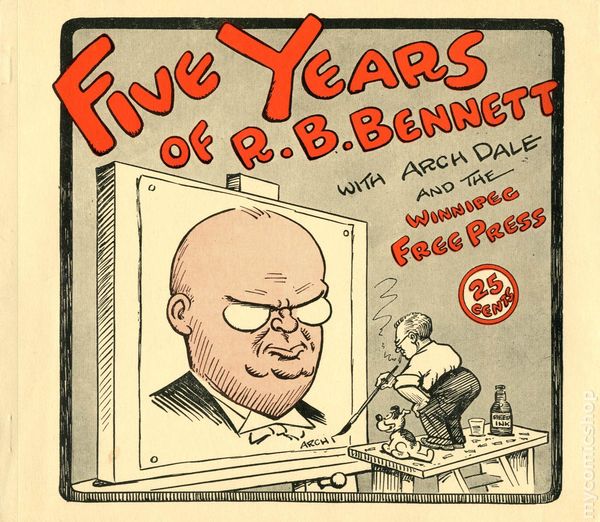

The Conservative government’s strong-arm tactics using Bennett’s “iron heel of ruthlessness”[39] had a devastating effect on Western Canadian support. The On-to-Ottawa Trek was a protest from BC headed to Ottawa and had been “violently broken up two thousand miles from its goal”[40]. 120 people were arrested at the July 1st, 1935 Regina Riot which ended a police officer’s life. Some confusion between historians exists over whether Bennett took control of the RCMP in Saskatchewan in order to hold them in Regina with Section 98 of the Criminal Code[41]. Other than the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919, the Regina Riot of July 1, 1935, is probably one of the larger civil disturbance in Canada history. Highly critical of Bennett’s ineffectual leadership, Struthers adds that the riot was a “fitting conclusion to Bennett’s five years in office for it symbolized the failure of the unemployment polices pursued by his administration”[42].

The Conservative government’s strong-arm tactics using Bennett’s “iron heel of ruthlessness”[39] had a devastating effect on Western Canadian support. The On-to-Ottawa Trek was a protest from BC headed to Ottawa and had been “violently broken up two thousand miles from its goal”[40]. 120 people were arrested at the July 1st, 1935 Regina Riot which ended a police officer’s life. Some confusion between historians exists over whether Bennett took control of the RCMP in Saskatchewan in order to hold them in Regina with Section 98 of the Criminal Code[41]. Other than the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919, the Regina Riot of July 1, 1935, is probably one of the larger civil disturbance in Canada history. Highly critical of Bennett’s ineffectual leadership, Struthers adds that the riot was a “fitting conclusion to Bennett’s five years in office for it symbolized the failure of the unemployment polices pursued by his administration”[42].

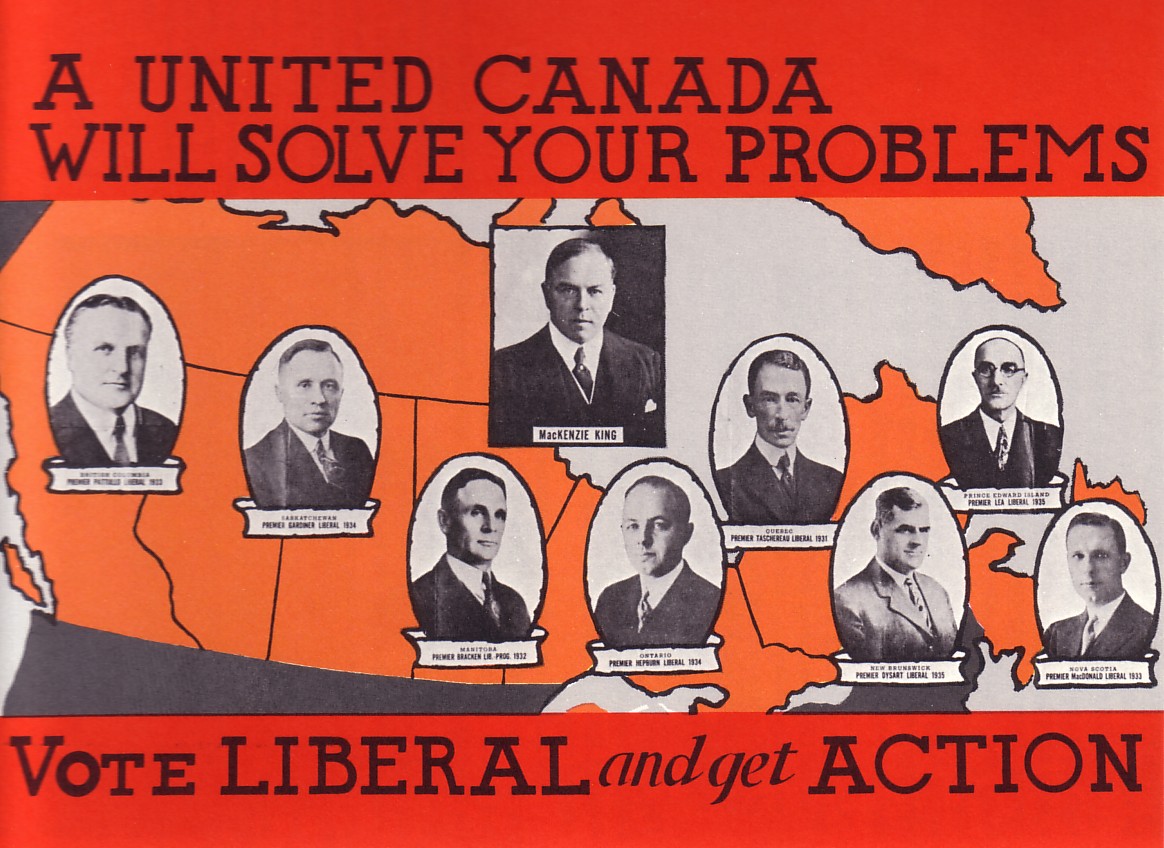

Out of desperation, R.B. Bennett turned to CBC public radio announcements in early 1935. Bennett’s New Deal echoed the interventionism of Roosevelt’s response to the Great Depression in 1933[43]. Developed by Bennett’s brother-in-law, Herridge’s New Deal attempted to placate the emergence of third party challenges in Western Canada. With projects to strengthen the Farm Loan Board etc, Diefenbaker claimed the broadcasts were enthusiastically received in Saskatchewan[44]. The obvious criticism that it took far too long in the term for the Western electorate who were mobilizing around new parties. The ‘Bennett Buggies’ had already been entrenched as a sarcastic criticism of the state of affairs. For Bennett it was too little too late and as Herridge ploy backfired[45]. King played the strategy of supporting the New Deal based on the merits of the proposal instead of allowing Bennett to use the bill as an election promise squandered by Liberal opportunism. King made no promises during the election campaign and won, the Regina Riots and the ‘slave camps’ ruined Bennett’s chances in Western where Social Credit and CCF were poised to split the vote. Other successes like providing for an eight-hour day, a six-day work week, and a federal minimum wage[46] are hardly observed in historical recollections or are deeply undervalued. While Bennett was, and is still, often criticized for lack of compassion for the impoverished masses, documents show that he stayed up through many nights reading and responding to personal letters from ordinary citizens asking for his help and often dipped into his personal fortune to send a five dollar bill to a starving family[47].

Out of desperation, R.B. Bennett turned to CBC public radio announcements in early 1935. Bennett’s New Deal echoed the interventionism of Roosevelt’s response to the Great Depression in 1933[43]. Developed by Bennett’s brother-in-law, Herridge’s New Deal attempted to placate the emergence of third party challenges in Western Canada. With projects to strengthen the Farm Loan Board etc, Diefenbaker claimed the broadcasts were enthusiastically received in Saskatchewan[44]. The obvious criticism that it took far too long in the term for the Western electorate who were mobilizing around new parties. The ‘Bennett Buggies’ had already been entrenched as a sarcastic criticism of the state of affairs. For Bennett it was too little too late and as Herridge ploy backfired[45]. King played the strategy of supporting the New Deal based on the merits of the proposal instead of allowing Bennett to use the bill as an election promise squandered by Liberal opportunism. King made no promises during the election campaign and won, the Regina Riots and the ‘slave camps’ ruined Bennett’s chances in Western where Social Credit and CCF were poised to split the vote. Other successes like providing for an eight-hour day, a six-day work week, and a federal minimum wage[46] are hardly observed in historical recollections or are deeply undervalued. While Bennett was, and is still, often criticized for lack of compassion for the impoverished masses, documents show that he stayed up through many nights reading and responding to personal letters from ordinary citizens asking for his help and often dipped into his personal fortune to send a five dollar bill to a starving family[47].

With the unavoidable crisis in Western Canada, the resignation of the popular H.H. Stevens in 1934, the “most talked of with regard to Reform in the West”[48], the formation of the Reconstruction Party (a renegade faction of Bennett’s party driven by a distrust of Bennett’s attachment to large corporations)[49] and the emergence of the Social Credit and Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, the Conservative party’s electoral revitalization for the 1935 election was doomed. It did not help that the organizing party machine put together by A.D McRae had died out in depression years[50]. Ultimately, the Conservative party could not solve the international problem of the depression. The result of Bennett’s failure was that the Western electorate rejected ordinary political parties for alternative expressions of protest. The public discontent in the West translated into electoral collapse losing half of all popular support in the four Western[51]. “Furthermore, despite the prevalence of hardship in western Canada, the depression would not bring immediate victory to the new party in the 1935 election”[52]. This position is expanded by Dough Owram, who points of that “the world was forced to operate in ruthless competition which creates maldistribution of wealth and ‘gives rise to the violent fluctuations in the purchasing power of consumers”[53].

Unable to overcome the Depression, Bennett lost the 1935 election to his Liberal opponent, Mackenzie King. New leaders gained support by promising to help struggling constituents and to stand up to Ottawa. Electoral math problem SMD screwed him 18.7% drop in the support in 1935 election from 1930 47.5%(site) wikipedia). His larger failings were in the dealing of specifics in Great Depression, particularly federal-provincial relations with the four western provinces, the DND camps and the Regina Riot. The massive majority gained by King is more telling of the single member district electoral system than Bennett’s failures. King actually didn’t need the west to make a massive majority. Stevens Reconstruction party took 8.7% directly out of the Conservative party caucus** How much of the depression is truly Bennett’s fault is impossible to gage and historians seem to debate over the depth of his ineptitude rather than the successes he achieved. The 1935 election sealed Bennett’s fate as a failed leader, but this is only one side of a complex diverging understanding of Bennett and his accomplishments under the most dire of circumstances. While various writers describe to a degree the details of R.B. Bennett’s political strategy during the depression, they vary on the emphasis of his success or failure. Stevens and Tim Buck came back to haunt him electorally speaking.

Unable to overcome the Depression, Bennett lost the 1935 election to his Liberal opponent, Mackenzie King. New leaders gained support by promising to help struggling constituents and to stand up to Ottawa. Electoral math problem SMD screwed him 18.7% drop in the support in 1935 election from 1930 47.5%(site) wikipedia). His larger failings were in the dealing of specifics in Great Depression, particularly federal-provincial relations with the four western provinces, the DND camps and the Regina Riot. The massive majority gained by King is more telling of the single member district electoral system than Bennett’s failures. King actually didn’t need the west to make a massive majority. Stevens Reconstruction party took 8.7% directly out of the Conservative party caucus** How much of the depression is truly Bennett’s fault is impossible to gage and historians seem to debate over the depth of his ineptitude rather than the successes he achieved. The 1935 election sealed Bennett’s fate as a failed leader, but this is only one side of a complex diverging understanding of Bennett and his accomplishments under the most dire of circumstances. While various writers describe to a degree the details of R.B. Bennett’s political strategy during the depression, they vary on the emphasis of his success or failure. Stevens and Tim Buck came back to haunt him electorally speaking.

At once a man of decidedly ill repute and a statesman often-misunderstood, R.B. Bennett did the best he knew how. Bennett receives a negative historical analysis because Canadian historians forget the philosophical mindset of the era. Unfortunately, Bennett is the antithesis of the welfare state; few can argue that Bennett was successful in his laissez faire policies. Had Bennett been re-elected, in a counter-factual analysis, his perceived ineptitude during the depression might have evaporated as World War II would have hailed him with the political capital and economic upturn needed. King and the Liberal Party were the beneficiaries of Bennett’s failure. In that sense, Bennett was Canadians history’s most sacrificial prime minister.

The success of the New Deal is in debate in the United States. 1937 there was another recession in the US. WWII was the ultimate solution.

Disclaimer: I don’t stand by any assertions in this paper; it was written 10 years ago and am not responsible for it’s content. So there!

Work Cited

Berton, Pierre. The Great Depression 1929-1939. Toronto: McClelland and Steward Inc, 1990.

Morton, Desmond. A Short History of Canada: Fifth Edition. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Ltd, 2001.

Orwam, Doug. The Government Generation: Canadian Intellectuals and the State: 1990-1945. Toronto: University of Toronto, 1986.

Seager, Allan and Thompson, Herd John. Canada 1922-1939: Decades of Discord, the Canadian Centenary Series. Toronto: McClelland & Steward Ltd, 1985.

Struthers, James. No Fault of Their Own: Unemployment and Canadian Welfare State: 1914-1941. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1983.

Maclean, D. Andrew. R.B. Bennett: The Prime Minister of Canada. Toronto: Excelsior Publishing Company, Ltd, 1934.

Waite, P.B. The Loner: Three Sketched of the Personal Life and Ideas of R.B. Bennett 1870-1947. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992.

Watkins, Ernest. R.B. Bennett: A Biography. London: Secker & Warburg, 1963.

Wilbur, Richard. The Bennett Administration: 1930-1935. Ottawa: The Canadian Historical Association Booklets, No. 24, 1969.

Walter D. Young. Democracy and Discontent: Progressive, Socialism and Social Credit in the Canadian West, Chapters 1-3: 1-56

Wikipedia, Canadian Federal Election, 1935.

[1] Given the context, his paradoxical compassionate letters to the poor while rejecting government intervention demonstrates that a philosophical discord within his Conservative ideology was a barrier to full scale government intervention. Intervention wouldn’t have amounted to much though BECAUSE I conclude, ultimately, that Bennett was screwed by forces beyond his or any Western nation. Only a war would help King in re-election.

[2] McKay, Ian. “The Liberal Order Framework: A Prospectus for a Reconnaissance of Canadian History”. Canadian Historical Review (2000), pp. 625.

[3] Waite, P.B. The Loner: Three Sketched of the Personal Life and Ideas of R.B. Bennett 1870-1947. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992, pp. 24.

[4] Waite, P.B, 54.

[5] Glasford, Larry A. Reaction and Reform: The Politics of the Conservative Party under R.B. Bennett, 1927-1938. University of Toronto Press, 1992, pp. 26.

[6] Struthers, James. No Fault of Their Own: Unemployment and Canadian Welfare State: 1914-1941. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1983, pp. 5.

[7] Young, Walter D. Democracy and Discontent: Progressivism, Socialism and Social Credit in the Canadian West: McGraw-Hill Ryerson Ltd., 1969, pp. 43.

[8] Watkins, Ernest. R.B. Bennett: A Biography. London: Secker & Warburg, 1963, pp. 181.

[9] (Morton, 211)

[10] Election speech, R.B. Bennett, June 9, 1930.

[11] Glasford, 96.

[12] Struthers, 48.

[13] Thompson and Seager in Canada 1922-1939: Decades of Discord,

[14] Berton, Pierre. The Great Depression 1929-1939. Toronto: McClelland and Steward Inc, 1990, pp 141.

[15] Glasford, 114.

[16] Struthers, 50.

[17] Part of Bennett’s legacy being the independent of the dominions within a new British Commonwealth.

[18] Wilbur, Richard. The Bennett Administration: 1930-1935. Ottawa: The Canadian Historical Association Booklets, No. 24, 1969, pp. 7.

[19] Seager, Allan and Thompson, Herd John. Canada 1922-1939: Decades of Discord, the Canadian Centenary Series. Toronto: McClelland & Steward Ltd, 1985, pp. 213.

[20] Struthers, 47.

[21] Ibid, 77.

[22] Berton, 136.

[23] Glasford, 121.

[24] Berton, 141.

[25] Struthers, 92.

[26] Seager, 268.

[27] Glasford, 122.

[28] Ibid, 121.

[29] Ibid, 123.

[30] Ibid, 117.

[31] Ibid, 116.

[32] Struthers, 145.

[33] Seager, 254.

[34] Glasford, 134.

[35] Wilbury, 17.

[36] Struthers, 95.

[37] Ibid, 122.

[38] Struthers, 96.

[39] Glasford, 121.

[40] Seager, 272.

[41] Berton, 323.

[42] Struthers, 136.

[43] Seager, 263.

[44] Glasford, 155.

[45] Glasford, 159.

[46] Seager, 264.

[47] Seager, 212.

[48] Glasford, 168.

[49] Ibid, 138.

[50] Ibid, 100.

[51] Conservative Popular Vote change 1930-1935: 49.3% – 24.9% BC, 35.0%-17.5% AB, 33.6%-18.0% SK, 44.1%-27.9% MB.

[52] Young, 55.

[53] Orwam, Doug. The Government Generation: Canadian Intellectuals and the State: 1990-1945. Toronto: University of Toronto, 1986, pp. 219.