1979 was a War-zone for Chrysler.

1979 was a War-zone for Chrysler.

In business, you need to be like an Army surgeon. You might have 40 injured people, but you only have 3 hours to save them. You need to pick the ones who have the best chance of survival. At Chrysler, there was no time to study a marginally performing car plant, you have to axe it immediately. You need to have discipline.

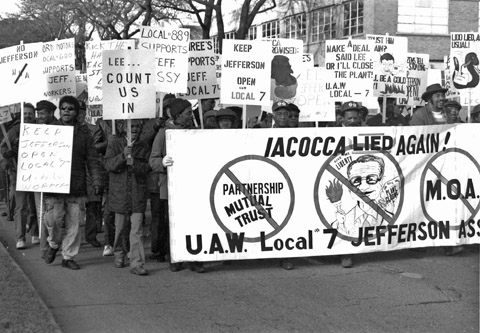

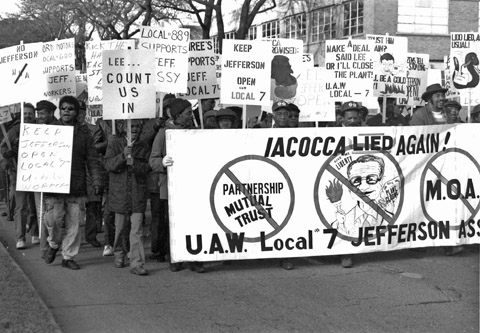

First, Iacocca’s team at Chrysler had to close plants in Lyons, Michigan and Dodge Main in Hamtramck, which was the Polish district of Detroit. There were major protests over these plant closures but Iacocca had no choice.

Next, Iacocca’s team at Chrysler had to reassure suppliers that they were going to be paid on time. They needed to demonstrate that Chrysler was not going into bankruptcy even though suppliers knew their business and Chrysler’s well.

Next, Iacocca’s team at Chrysler had to reassure suppliers that they were going to be paid on time. They needed to demonstrate that Chrysler was not going into bankruptcy even though suppliers knew their business and Chrysler’s well.

Then, Iacocca’s team at Chrysler brought in just-in-time inventory delivery. The Japanese had been doing this for years but as far back as the 1920s, Ford’s River Rouge Plant had taken ore from the boats, converted it into steel and then turned that into engine blocks within 24 hours. Ford Motor Company had just in time but with the boom years fro 1945 to 1978, the US car industry fell into old habits and lethargy.

Next, Iacocca’s team at Chrysler designed the K-cars to be 176 inches long (14’ 8’’) so that they could fit into a standard freight car. Even the financial report for 1979 was printed on cheap document paper.

Next, Iacocca’s team at Chrysler designed the K-cars to be 176 inches long (14’ 8’’) so that they could fit into a standard freight car. Even the financial report for 1979 was printed on cheap document paper.

Then, Iacocca’s team at Chrysler sold all the dealership real-estate they owned to ABKO from Kansas. The cash came to $90 million, which was desperately needed (timing matters), then later Iacocca had to buy back half of that property at twice the original price!

Next, Iacocca’s team at Chrysler sold all their non-North American businesses. Peugeot bought their European operations for $230 million and a 15% stake in Peugeot. They sold their military tank operations for $348 million to General Dynamics. Interestingly, the union negotiations at the time forced workers to $17 per hour instead of $20 per hour, so General Dynamics got a cheaper labour force when the contract was signed between Chrysler and General Dynamics.

Next, Iacocca’s team at Chrysler sold all their non-North American businesses. Peugeot bought their European operations for $230 million and a 15% stake in Peugeot. They sold their military tank operations for $348 million to General Dynamics. Interestingly, the union negotiations at the time forced workers to $17 per hour instead of $20 per hour, so General Dynamics got a cheaper labour force when the contract was signed between Chrysler and General Dynamics.

Then, there were major layoffs in waves from 1970 and then 1980, both blue and white collars. This saved Chrysler $500 million in annual costs. Iacocca admits that some of firings were tragic and mistakes. Firing people is never a positive experience.

Then, there were major layoffs in waves from 1970 and then 1980, both blue and white collars. This saved Chrysler $500 million in annual costs. Iacocca admits that some of firings were tragic and mistakes. Firing people is never a positive experience.

Next, Iacocca’s team at Chrysler fired the staff who had integrated the work of the line managers into a workable system. These were the Harvard Business School graduates who had never run anything, but were now telling the line manager who had done the job for 30 years how it ought to be done. Iacocca always trusts people with a dedicated background in the industry over elite educated people.

Then, Iacocca went shopping for people to buy into Chrysler. This included Volkswagen which was a very serious discussion because Chrysler was dying. The stock jumped form $11 to $14 upon the news that Volkswagen would buy for $15 shares but this was a false story.

Then, Iacocca went shopping for people to buy into Chrysler. This included Volkswagen which was a very serious discussion because Chrysler was dying. The stock jumped form $11 to $14 upon the news that Volkswagen would buy for $15 shares but this was a false story.

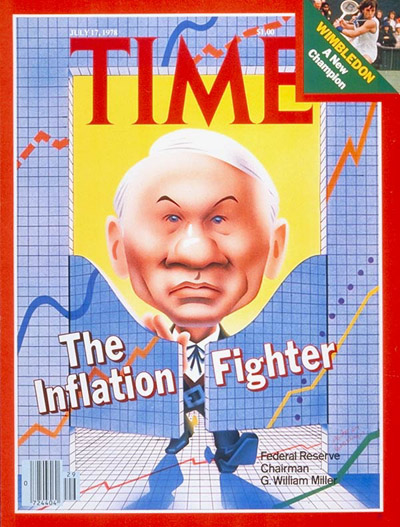

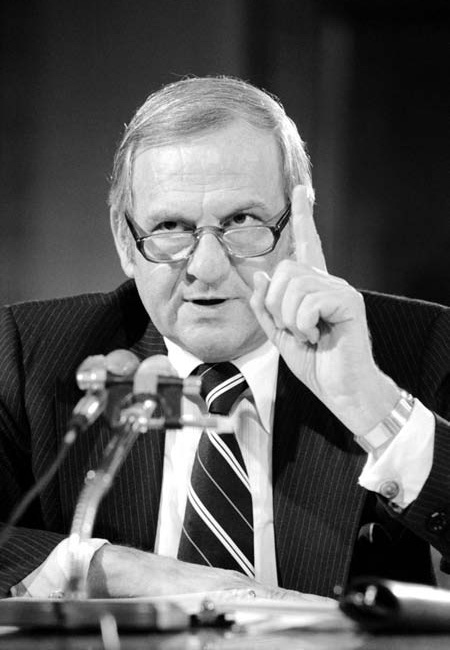

Finally, there was the big government bailout.

This is a synopsis & analysis based on Iacocca: An Autobiography and other miscellaneous research sources. Enjoy.

This is a synopsis & analysis based on Iacocca: An Autobiography and other miscellaneous research sources. Enjoy.

Issues of Scope: What can our business do? What can it own? Where can it operate? General Electric’s approach is to say that its separate businesses should be ranked one or two in whatever sector they operate. If that business isn’t near the top, then GE sells it because they don’t want to be associated with mediocrity. McDonald’s decided long ago to get involved in franchising, rather than owning millions of parcels of real estate. Sound contracts and long-term relationships can be far less hassle than ownership. The ownership and value tests are more relevant in a globalized world…Could an American company with global ambitions adapt to new countries and cultures and run businesses better than local firms? Did global growth allow you to reduce your costs? What are the realities of doing business abroad?

Issues of Scope: What can our business do? What can it own? Where can it operate? General Electric’s approach is to say that its separate businesses should be ranked one or two in whatever sector they operate. If that business isn’t near the top, then GE sells it because they don’t want to be associated with mediocrity. McDonald’s decided long ago to get involved in franchising, rather than owning millions of parcels of real estate. Sound contracts and long-term relationships can be far less hassle than ownership. The ownership and value tests are more relevant in a globalized world…Could an American company with global ambitions adapt to new countries and cultures and run businesses better than local firms? Did global growth allow you to reduce your costs? What are the realities of doing business abroad? Dispersed Manufacturing/Li and Fung: Li and Fung was founded in Canton in 1906 to help American and English merchants to access Chinese factories. It now manages the supply chain for many of the world’s largest retailers and manufacturers. Li and Fung built their business by expanding to Singapore, Korea, Taiwan. If you wanted to make shirts in Asia, Li and Fung would find the cotton businesses, and then move the unfinished product cheaper than if you picked a single factory. This is called dispersed manufacturing, and they don’t own any of these factories. There is a fragmented global supply chain, and the tiniest step requires specialization. Li and Fung helps customers through the maze.

Dispersed Manufacturing/Li and Fung: Li and Fung was founded in Canton in 1906 to help American and English merchants to access Chinese factories. It now manages the supply chain for many of the world’s largest retailers and manufacturers. Li and Fung built their business by expanding to Singapore, Korea, Taiwan. If you wanted to make shirts in Asia, Li and Fung would find the cotton businesses, and then move the unfinished product cheaper than if you picked a single factory. This is called dispersed manufacturing, and they don’t own any of these factories. There is a fragmented global supply chain, and the tiniest step requires specialization. Li and Fung helps customers through the maze.