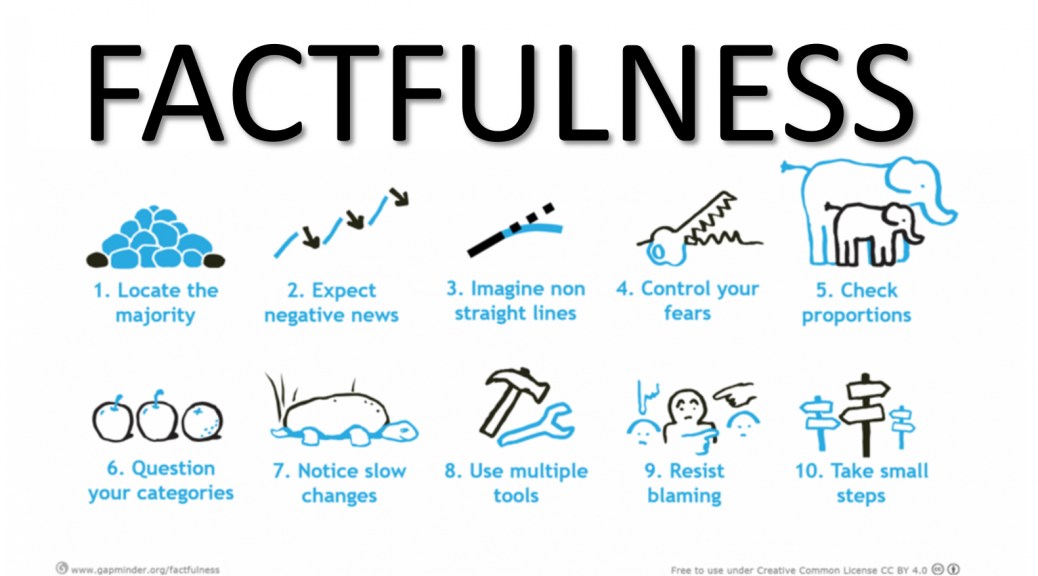

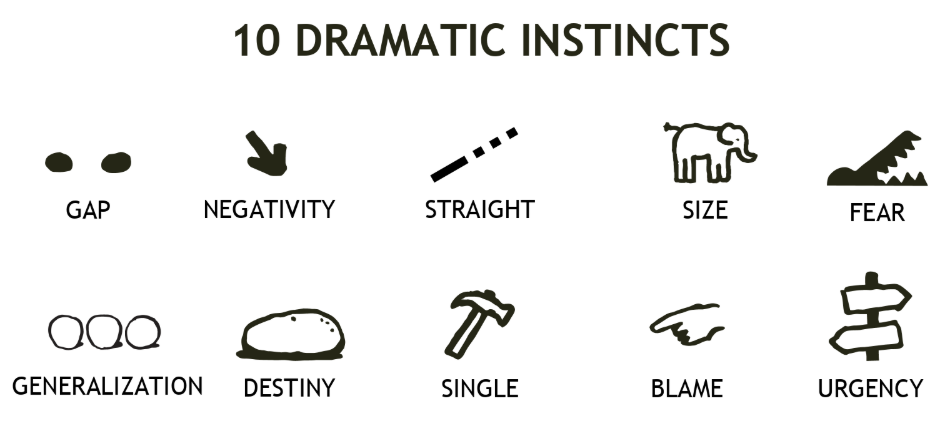

The following is a synopsis of Factfulness by Hans Rosling. It’s a great read on the Ten Reasons We are Wrong About Everything and Why Things are Not as Bad as We Think

Introduction: Why I Love the Circus

Hans Rosling was a physician, academic and public speaker. Together with his son, Ola Rosling and his daughter in law Anna Rosling Ronnlund, he founded the Gap Minder Foundation in 2005 to fight ignorance and encourage what he calls a more factful approach to life. Although this book, like his TED Talks, was written in his voice it is a collaboration between the three of them.

Although he pursued a career in medicine and became a leading academic, Rosling’s true passion as a child was the circus. He loved everything about it and was convinced he would one day live his dream and run off to become a performer. His parents had other ideas; they wanted him to enjoy the first-rate education they didn’t have and so he studied medicine instead.

When studying medicine, he discovered he could stick his hands down his throat further than anyone else. For a short time, he dreamed once again of joining the circus as a sword swallower. Because swords were in short supply, he decided to start with a fishing rod, but found it impossible. It was only later, when treating an actual sword swallower, that he learned the reason why he had failed.

The throat, he was told, is flat and can only take flat objects. To his delight he discovered he could actually do it and, later in life when he began giving talks, he often used it as a finale to his act.

He talks about sword swallowing for a reason. It’s one of those ideas which inspire people to think differently, to question perceptions and, as such, to accomplish the seemingly impossible. This is a key feature of the book.

Another is the continual need to test yourself and question your assumptions. To illustrate he lists 13 questions:

- How many girls finish primary school in low income countries around the world?

- Where does the majority of the world’s population live: low income, middle income or high-income countries?

- In the last 20 years, the number of people living in extreme poverty has increased or halved?

- What is the life expectancy of the world today?

- There are 2bn children aged 0 to 15 years old. How many will there be in the year 2100 according to the UN?

- The UN predicts that, by 2100, the world’s population will have increased by 2bn. Why is this: more younger people or more older people?

- How has the number of deaths from natural disasters changed over the last 100 years?

- There are 7bn people in the world. Where do they live: mostly in Europe, Africa, Asia or America?

- How many of the world’s one-year old children today have been vaccinated?

- 30-year-old men have spent ten years in school on average. How many years have women of the same age spent?

- In the 1990s tigers, giant pandas and black rhinos were all listed as endangered. How many are listed as more critically endangered than they were then?

- How many people in the world have access to some electricity?

- Over the next 100 years will the average temperature get warmer, stay the same or get colder?

He sets these tests to people around the world and the majority get them wrong. Our perception of the world is far removed from the reality. His aim in the book is to give people the tools to think in a factful manner, to challenge perceptions and understand the world more completely.

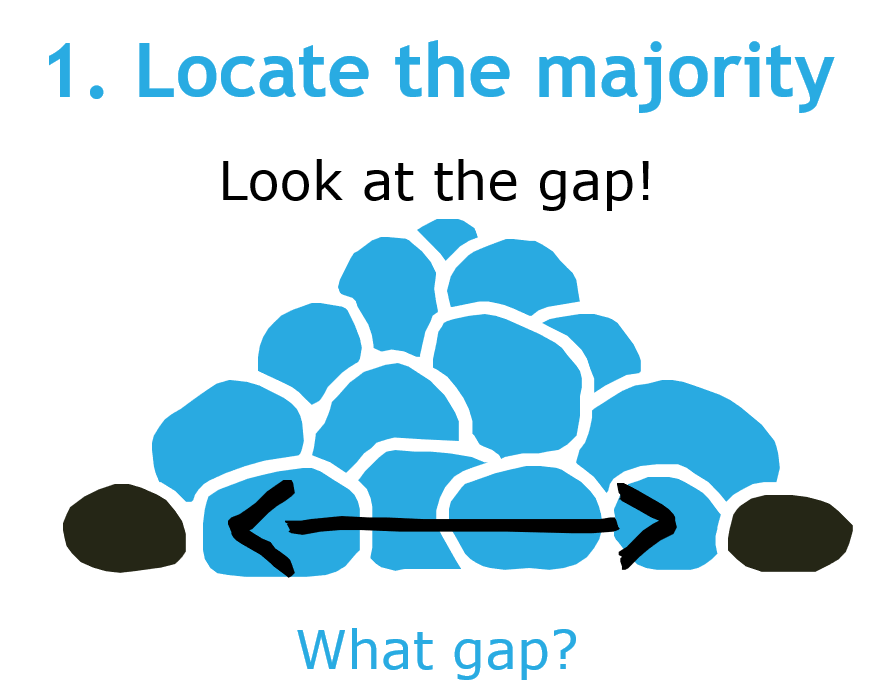

Chapter 1: The Gap Instinct

Our world view is often distorted thanks to the tendency to divide everything into two extremes with a space or a gap in between. For example, we often view the world through the perspectives of distinct groups such as ‘rich versus poor’, ‘us versus them’ or ‘developed and developing countries’.

This is simple and makes it easy to develop a view of the world, but he believes it’s wrong.

To demonstrate his point, he looks at our tendency to divide the global population into developing and developed countries. Those in developed worlds have better access to healthcare, live longer lives and have better access to electricity, while those in the developing world do not. However, the data shows that most people have access to all these things.

In reality, most countries fall into a gap between the perceived developed and developing worlds, with many moving towards the group of developed countries. As such, this divisive world view makes no sense.

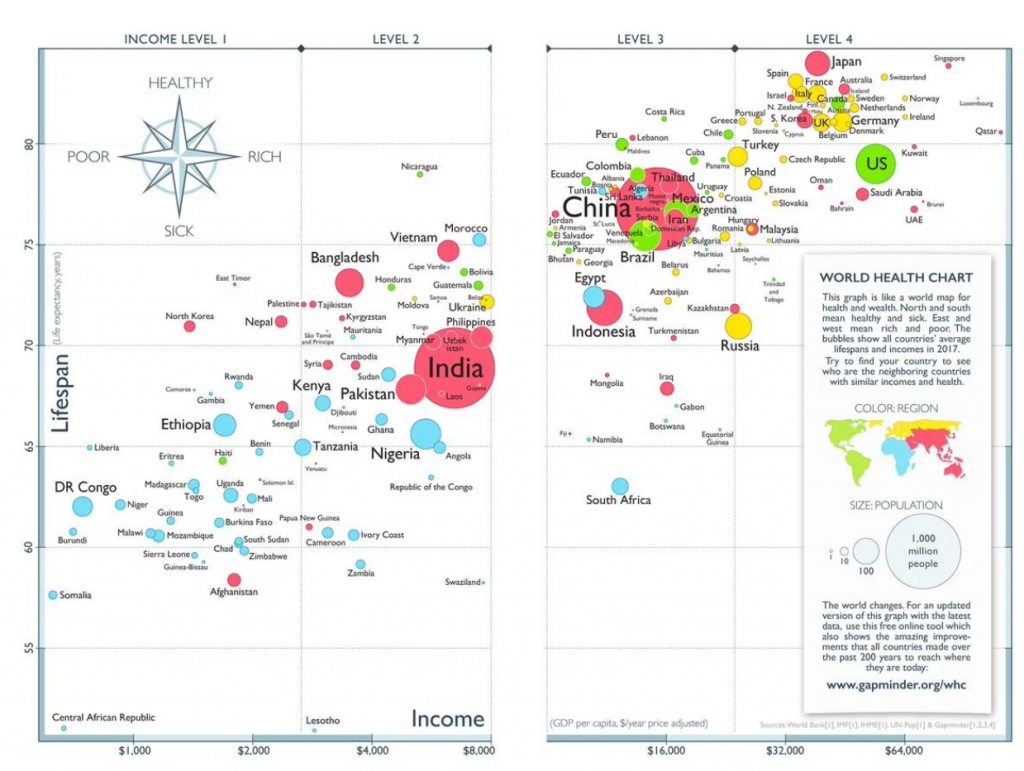

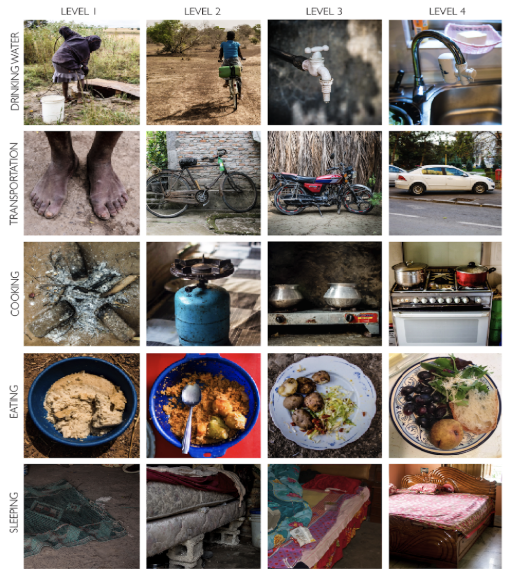

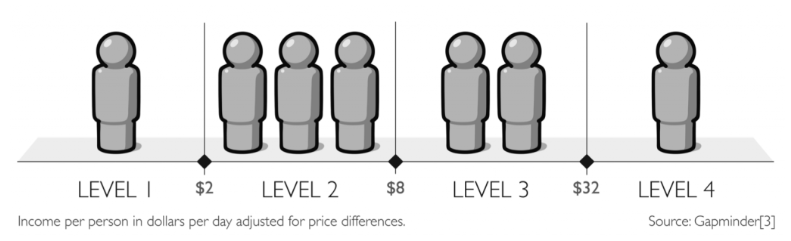

Instead, he introduces four categories which can provide us with a better view of the world. These are:

Level 1: Earning less than $2 per day.

Level 2: Earning between $2 and $8 per day.

Level 3: Living off$8 to $32 per day.

Level 4: Bringing in more than $32 each day.

It doesn’t matter where you live in the world; people in each group tend to have a similar quality of life. Those in Level 1 suffer from poor nutrition, live hand to mouth and rely on walking to get where they need to go. In Level 2 people are better off; they can feed themselves have better access to electricity and education but they are not secure. At any time, an emergency could see them slip back to Level 1. At the top is Level 4 in which people can afford a car and an annual holiday.

This produces a more accurate view of the world, one which divides people by quality of life rather than simply where they are living. Even so, the traditional gap-based view of the world prevails.

To combat this, he cites a number of warning signs which can encourage us to slip into the gap-based world view.

- Comparing averages between two situations. We forget about the overlap which creates the illusion of a gap.

- Comparing extremes: For example, thinking of the poorest versus the richest is wrong because most people are in neither extreme.

- View from above: People in higher income levels look down on lower levels without any idea of the conditions in those levels. If you’re in Level 4, you might think of people in levels 2 and 3 as being poor when in fact they have a much better quality of life than you might think.

The reality of life is that there is no gap. Most people exist in the middle where the gap is supposed to be. Thinking about people in two groups distorts our view of the world. To form a fact-based world view, we have to recognise that many of our perceptions are filtered through mass media which loves to focus on examples which are extraordinary or extreme.

“There is no gap between the West and the rest, between developed and developing, between rich and poor,” Rosling writes. “And we should all stop using the simple pairs of categories that suggest there is.”

Chapter 2: The Negativity Instinct

“The world is getting worse”. It’s a view that we hear often and which, according to polls, most people share. However, it is also wrong. In truth, the world is getting better. We simply don’t notice when it does.

Most humans pay attention to the bad rather than good. As such, they believe the world is only getting worse.

There is some truth in this. The environment is deteriorating and terrorism is higher than it was 30 years ago. Even so, the state of the world is generally improving. However, according to Rosling, these improvements go unnoticed because they aren’t reported and we look back at the past through rose tinted spectacles.

Instead, minor setbacks receive greater coverage. If you look at the news, you’ll be forgiven for assuming that the world is set on a downward trend. However, the facts tell another story.

In the 1800s most people in the world were at income Level One. Extreme poverty was the norm for most people in the world. Today, only 9% of the world is still at level one. Life expectancy has improved from 31 years in the 1800s to over 70 years today. Slavery has been abolished, child mortality is down; plane crashes, hunger and deaths in battles have decreased. Access to electricity, water and health have improved.

Even so, the negative world view persists.

This view is caused by three things: mis remembering the past, selective reporting and the feeling that it would be insensitive to say things are getting better when they are still bad for many people.

When people start living better lives, they can forget how bad things were. They romanticise their youth.

Most reporting is negative. Good news is not news and neither are gradual improvements. A successful flight receives no coverage, but a crash will be splashed across all media outlets.

Rosling suggests three ways to control this negativity instinct.

- Remember that ‘bad’ and ‘better’ are not mutually exclusive. Things can be bad but they can also be better than they were before. Saying things are better should not be confused with believing everything is fine.

- Expect bad news. If we recognise that news is likely to disproportionately highlight negatives, we can be better prepared for it. Factfulness is remembering that most of the news which reaches us is bad news and there are plenty of positive developments in the world which do not make headlines. More news does not necessarily mean things are getting worse. It could equally mean that we are getting better at monitoring this suffering, which in turn will make it easier to alleviate it.

- Avoid romanticising the past. Life was not as good as we think it was, if we present history as it was, we can realise that life, in general, is getting better.

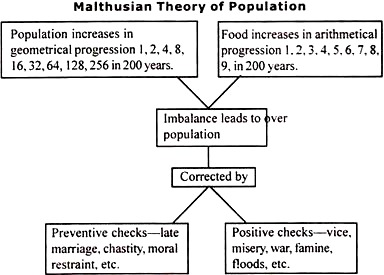

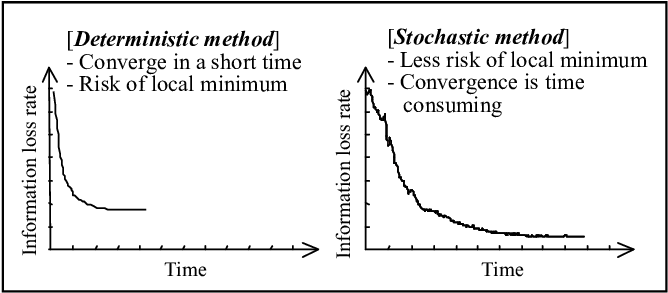

Chapter 3: The Straight-Line Theory

Life does not always work in a straight line, but our thinking does. In this chapter Rosling examines our tendency to assume a certain trend will continue along a straight line in perpetuity. Reality is very different but our straight-line instinct stops us seeing life as it truly is.

He talks about an Ebola outbreak in Liberia. Like most people, he assumed the number of cases would continue in a straight line with each person infecting, on average, another person. As such it would be relatively easy to predict and control as most other outbreaks of disease are. However, he came across a WHO report which said the number of infections was doubling with each case. Every person infected two more people on average before dying.

This spurred him into action. He discusses an old Indian legend. Krishna is challenged by the King to a game of Chess and asked to name his prize if he wins. Krishna asks for one grain of rice to be placed on the first square with the number doubling with each square.

The King agrees assuming it will increase in a straight line. However, it takes him a little while to realise that, by the time it gets to the 60th square, he would have to find more rice than the entire country could produce.

Many people assume the world’s population is increasing. If nothing is done it will reach unsustainable levels meaning something drastic must happen to stop this tend getting any worse. However, UN data shows the rate of population increase is slowing. As living conditions improve, the number of children per family is falling. Instead, growth can be controlled by combatting extreme poverty.

Rosling uses the example of a child. In their first few years, babies and toddlers grow rapidly. If you were to extrapolate that growth for the future, ten-year olds would be much taller than they are. Of course, we know that doesn’t happen because we are all familiar with how the rate of growth slows over time.

When faced with unfamiliar situations, we assume a pattern will continue in a straight line. Instead, he suggests we should remember that graphs move in many strange shapes, but straight lines are rare. For example, the relationship between primary education and vaccination is an S curve; between income levels in a country and traffic deaths is a hump and the relation between income levels and number of babies per women is a slide.

We can only understand the progression of a phenomenon by understanding the shape of its curve. Assuming we know what will happen leads to erroneous assumptions and false conclusions which will in turn lead to ineffective solutions.

To control the straight-line instinct, we must remember that curves come in many forms and we will only be able to predict it when we understand the shape of its curve.

Chapter 4: The Fear Instinct

“Critical thinking is always difficult,” writes Rosling, “but it’s almost impossible when we are scared. There’s no room for facts when our minds are occupied by fear.”

This is why the ‘fear instinct’ can be so destructive. When people are afraid, their ability to tell fact from fiction falls off dramatically. Factfulness demands that we control our fear.

Never before has the image of a dangerous world been broadcast more widely and more effectively than it is today. We are frightened of almost everything, but the truth of the matter is that the world has never been safer or less violent.

Rosling starts the chapter by looking back to an old story from his days as a junior doctor. It was 1975 and news came in of a plane crash. The survivors were being rushed to his hospital; senior staff were at lunch which would leave just him and a nurse to handle the situation.

It would be his first emergency and, in his panic, he confused one of the survivors for a Russian pilot and became convinced Russia was attacking Sweden. He mistook a colour cartridge for blood and was narrowly stopped from shredding through a G suit worth thousands of dollars.

Fear stopped him from seeing the situation for what it was. Our minds have an attention filter which decides what reaches it. This is the useful. The word contains vast amounts of information and we have to filter it to avoid overload. However, what gets through tends to be the unusual or scary.

This is why newspapers are full of events which are frightening. However, the more of the unusual we see, the more we become convinced the unusual is actually the norm. Our fear instinct has been baked into our minds by millennia of evolution. Fear kept our ancestors alive, but even though many of these dangers have gone, the perception remains.

The dangers are more real for people in Level 1 and 2 income categories because they are more likely to suffer threats. For example, they might be more likely to be bitten by a snake which might make them jump if they see a funny shaped stick. However, for people in higher income levels, being bitten by a snake is much less likely. Even if they were to be bitten, they have access to good healthcare.

For them, the fear of the snake does more harm than good. Newspapers know these fears are hardwired into our brains so they use it to grab our attention. The same fears which kept our ancestors alive are keeping journalists employed today.

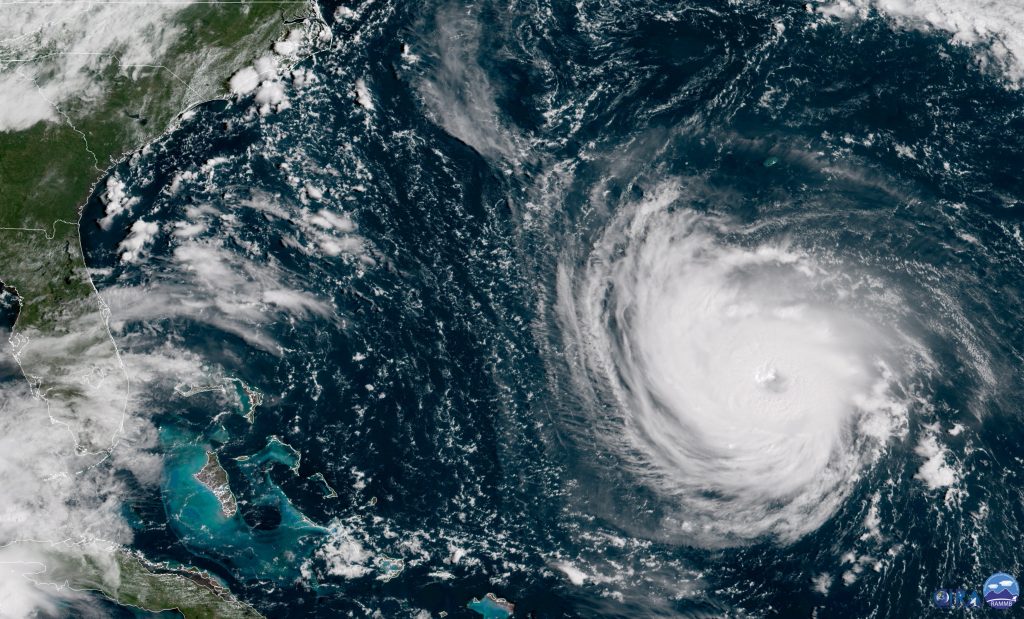

The number of deaths from natural disasters has fallen as countries develop better healthcare and infrastructure. Organisations, such as the WHO and UN, help victims in these situations but people in Level 4 aren’t aware of their success because the media reports it as the most serious disaster in history.

It is important to look at things with a fact-based approach to make better use of resources. For example, the 2015 earthquake in Nepal which killed 9,000 people attracted global attention, but diarrhoea from contaminated water kills 9,000 children each year but receives very little attention in comparison.

2015 was the safest year in aviation history but this fact was not reported. The number of deaths from battle has fallen and so has the threat of nuclear war. All these good pieces of news slip under the radar.

Following the Tsunami in 2011, 1,600 people died escaping Fukushima while nobody died from what they were running away from. Fear of chemicals such as DDT leads to deaths which could have been treated by DDT. The fear of an invisible substance leads to more harm than the substances itself.

Terrorism causes fewer deaths than alcohol but receives far more publicity.

Fear is a terrible guide for understanding the world. We pay attention to things we are afraid of but ignore things which can do us harm. Factfulness is knowing how to tell the difference between actual risks and perceived risks.

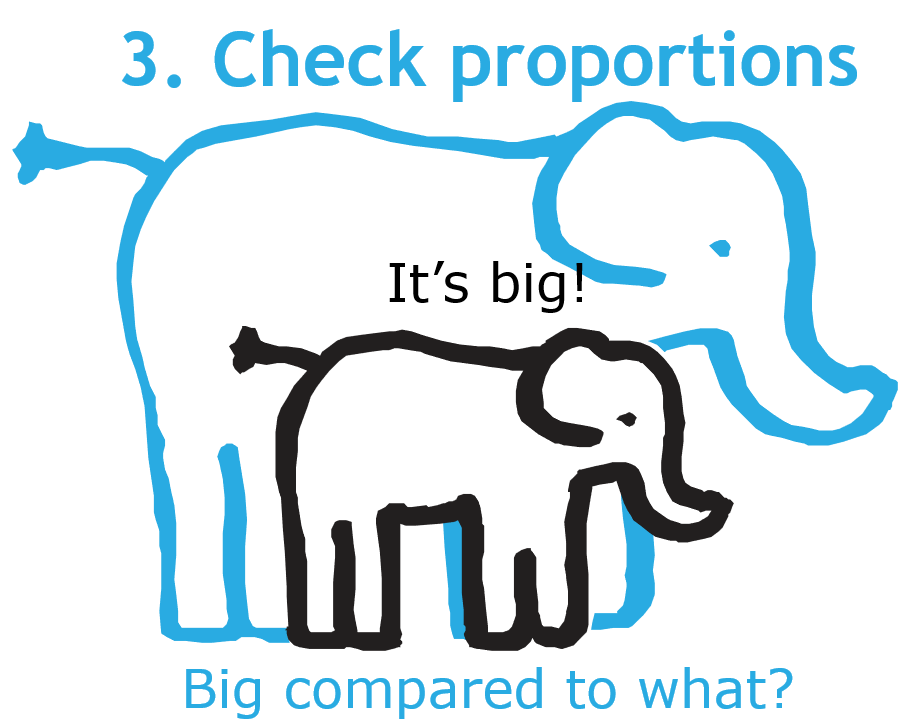

Chapter 5: The Size Instinct

From immigration to the number of deaths in hospitals, we consistently overestimate size. In this chapter, Rosling shows how this leads to a distorted view of reality and warps decision making.

He starts by going back to his time as a young doctor in Mozambique in the 80s when it was the world’s poorest country. One in 20 children died. He argued with a friend about the standard of treatment at the hospital. He felt they needed to provide better care outside of the hospital, but his friend believed he should concentrate on improving care within the hospital.

He decided to look at the number of children who died in the hospital compared to those who died outside. To his surprise he found that, while deaths were comparatively low inside the hospital, over 3,900 people died in the community. He therefore decided to go out into the community to provide better care to people who couldn’t get to the hospital.

When looking at a single number in isolation, it is easy to give it too much importance. For example, when he saw he was saving 95% of the children who came to the hospital it was easy to assume he was doing a great job. However, when he compared it to those who were outside the hospital, he realised he had to do more.

Journalists always give us numbers and exaggerate their importance. It leads to solutions which do not help. At the hospital, people would have assumed increasing the number of beds would reduce deaths but, with more information at their disposal, they realised the best path was to improve the levels of care and education within the community.

To avoid the trap of the size instinct, he recommends using the tools of comparison and division.

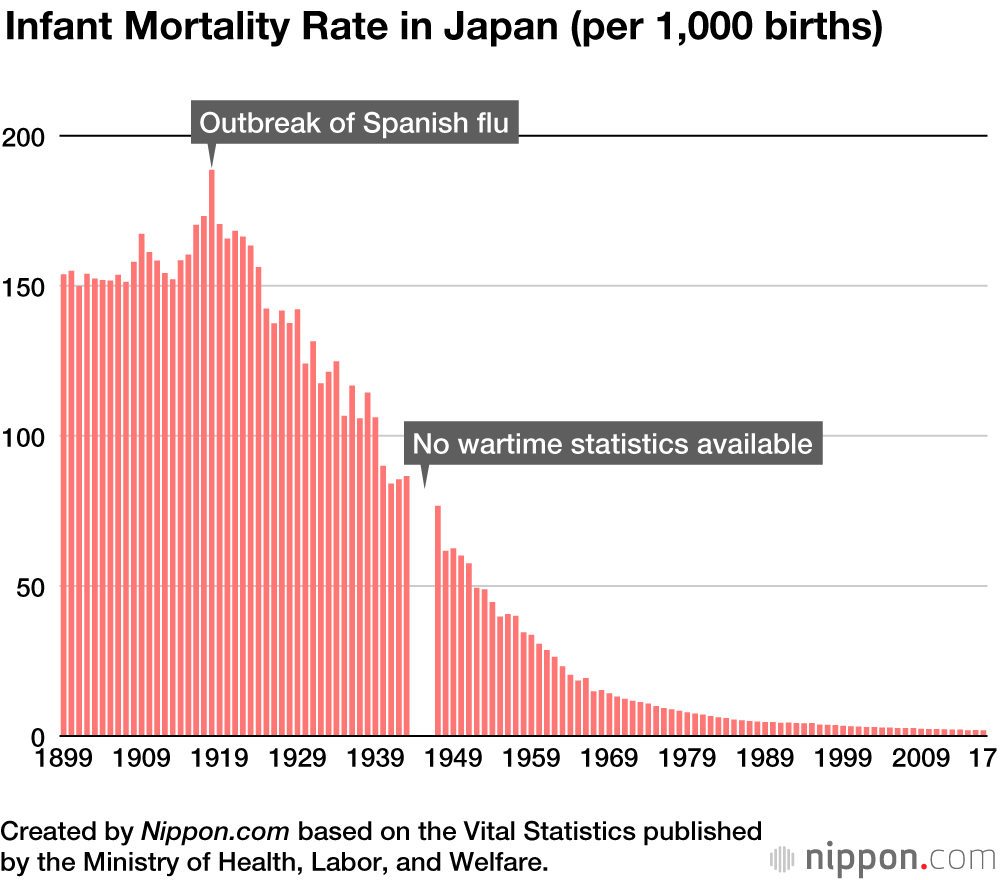

For example, two million children died before the age of one in 2016. This seems high until you compare it with 1950s number when 14.4 million children died before their first birthday. Infant deaths are falling, but you wouldn’t know this if you only looked at the first figure.

A Swedish hunter killed by a bear received more coverage than a woman killed by her husband. The first incident was a freak event; but it received far more coverage than the second which is a far more common and serious risk. Rather than being concerned by domestic violence, the media became obsessed with an event which is unlikely to happen again for many years.

Another example comes from the Swine flu epidemic which killed 31 people in 2 weeks. However, 63,000 people died from TB in the same period, but it received no coverage.

The lesson is that we tend to over state the unusual and ignore issues which are far more common. It distorts our world view and leads us to make poor decisions. Factfulness is understanding that just because something is more widely reported, doesn’t make it more common.

Chapter 6: The Generalisation Rule

As humans, we love to categorise and generalise everything. While this can help us to simplify our view of the world, it can also lead to distortions. Attributing one characteristic to an entire group based on one unusual example leads to serious misconceptions and can have quite serious consequences.

As he writes, the generalisation instinct “can make us mistakenly group together things, or people, or countries that are actually very different. It can make us assume everything or everyone in one category is similar. And, maybe most unfortunate of all, it can make us jump to conclusions about a whole category based on a few, or even just one, unusual example.”

For example, he begins the chapter by talking about his experiences working in the Congo when he was presented with a less than appetising dessert made from lava. To avoid eating it, he tried to convince them that it was against Swedish custom to eat lava.

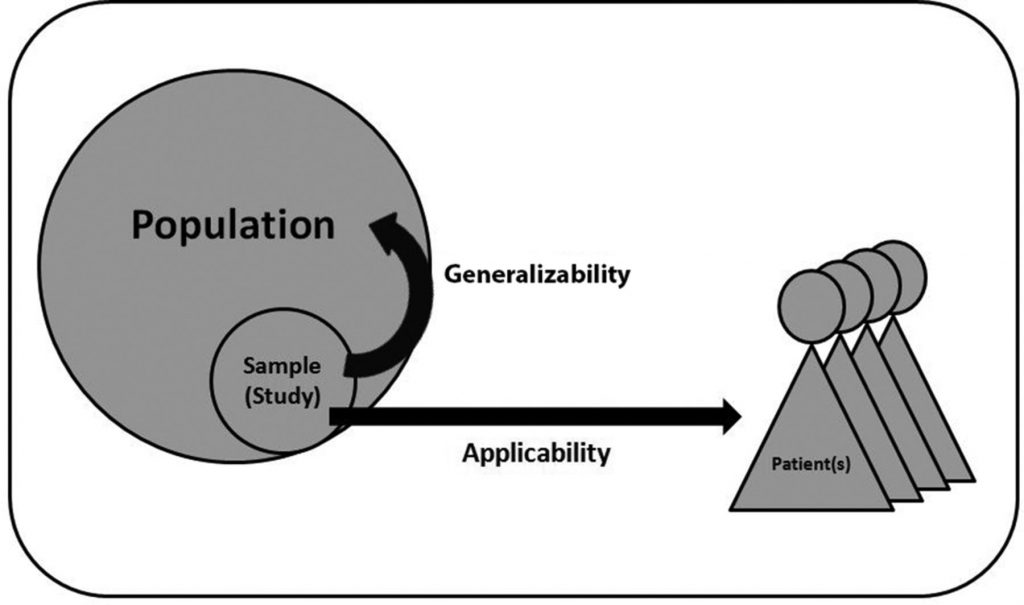

Generalisations, he says, are mind blockers. They create a distorted view of reality and often lead people to miss important opportunities. For example, after polling financial experts, he says, he found that they assumed most children in the world were not vaccinated before the age of one. In fact, the vast majority are. For that to happen, countries need a lot of infrastructure, which is also the same kind of infrastructure which is required for factories and other forms of enterprise.

The belief persisted because these financial experts believed the images of extreme poverty presented about some countries in the media. As such, these experts were potentially missing out on investment and business opportunities because they believed these countries were more deprived than they were.

To combat the generalisation instinct, he suggests travelling. This helps you to get out into the world and gain first-hand experience of cultures as they actually exist, rather than the way they are portrayed in the press.

As with other chapters, questioning is vital. You should always question the different categories you are given. Look for similarities across and within groups; remember to be suspicious of generalisations and to be aware when you are generalising one particular group from another.

Many people generalise African countries but they are not all at the same level of development. This has enormous consequences. The Ebola epidemic in Liberia affected tourism in Kenya even though the two countries are thousands of miles apart.

Majority is an extremely blunt concept. It can be anything between 51% and 99%; which does not produce a realistic picture of any situation.

Examples give a poor picture. Many people around the world suffer from chemophobia, the fear of chemicals, when in reality most are beneficial.

Assuming you are normal can lead to you generalising others and failing to understand the reasons behind their actions. What is normal to you is not necessarily normal to other people.

Factfulness is recognising what categories are used and keeping in mind that these categories can be misleading. While humans categorise and generalise everything, this can lead to stereotypes which can lead to poor solutions. By travelling and questioning assumptions, you can combat the problems caused by the generalisation instinct.

He also focuses on what he calls the 80/20 rule. We should always look at items which take up more than 80% of the total. Looking at the world’s energy sources, for example, you might feel they seem equally important, but only three generate more than 80% of the world’s energy.

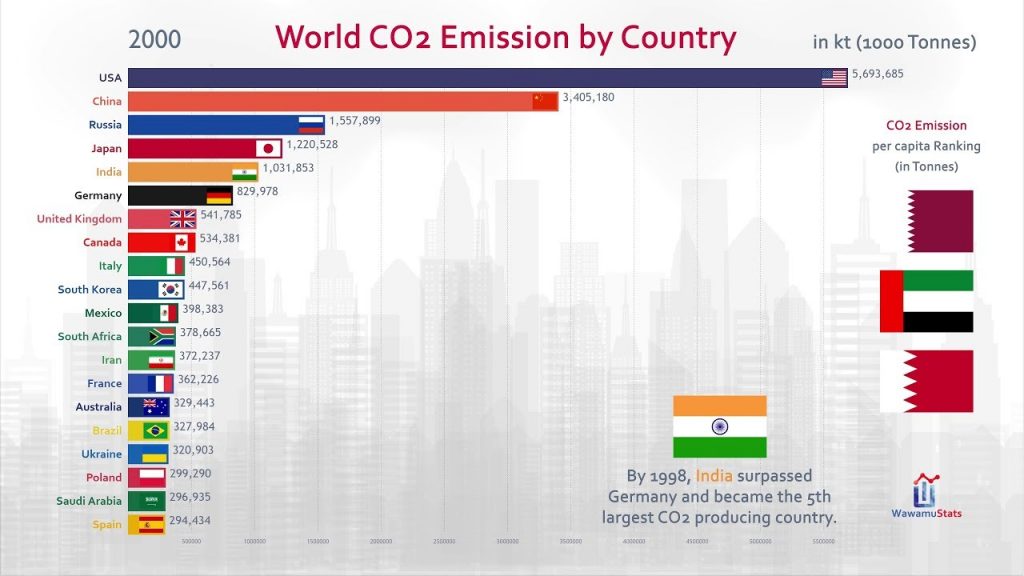

Divide it by a total to get a clearer idea of the situation. If you look at the total emissions produced by each country, it might seem that China and India produce more Co2 emissions than Germany and the USA, but if you divide it by the population, you’ll see that USA and Germany produce more emissions per head than either China or India. A single number does not provide a clear picture of any situation.

Chapter 7: The Destiny Instinct

When Rosling gave a presentation to a group of capitalists and wealthy individuals about the opportunities of emerging markets in Asia and Africa he was surprised by their reaction.

At the end of the talk he was approached by what he describes as a ‘grey haired’ man who told him, in no uncertain terms, that there was no chance that African countries would ever make it. Despite all the positive data about economic progress he’d seen in the presentation, this man believed there was something about African society which meant they were destined to be poor.

This is an example of the destiny instinct and its roots go back to the earliest history of man. As humans, we often assume that a nation, group or culture’s destiny is determined by general characteristic which we believe it shares. For example, white Europeans are destined to be developed and wealthy while black Africans will always be poor.

This attitude persists even in the face of contradictory data. Not only do people believe it to be true, but they assume there is nothing that individuals in this culture can do to change things. Destiny, as they say, is all.

The instinct stems from evolution when people lived in small groups and didn’t travel very far. It was safer to assume things would stay the same as they wouldn’t need to constantly evaluate the surroundings. It’s also a great way to unite a group.

However, today’s societies are constantly changing. These changes occur gradually which gives the perception that things are staying the same. As such, gender equality is perceived to have remained unchanged around the world, but in reality, things have largely improved.

There is also an idea that Africa is destined to remain poor. However, most African countries have reduced their infant mortality rates faster than Sweden did. Asian countries have moved into the category of developed nations and many countries have escaped extreme poverty.

It was also assumed that the number of babies a woman has would depend on her religion. Religious women were more likely to have babies than those with no religion. However, careful analysis of data shows that the number of babies depends not on religion but income levels.

Other examples include the rise of support for women’s rights and liberal ideas in Sweden. Concepts which might have been far from the mainstream in the past are now commonly accepted.

To control the destiny instinct, you should recognise that:

- Slow change does not mean no change at all.

- Be ready to update your knowledge. Knowledge is never constant in the social sciences.

- Collect examples of cultural change.

Factfulness is the art of recognising that many things appear to be static just because change is happening more gradually. Groups are not defined by their innate characteristics and, just because something has been true once, it doesn’t mean it is set in stone for the future. Like many of the other attitudes discussed in this book, the destiny instinct is hard coded into our evolution, but while it might once have been helpful for our ancestors, it is holding us back today.

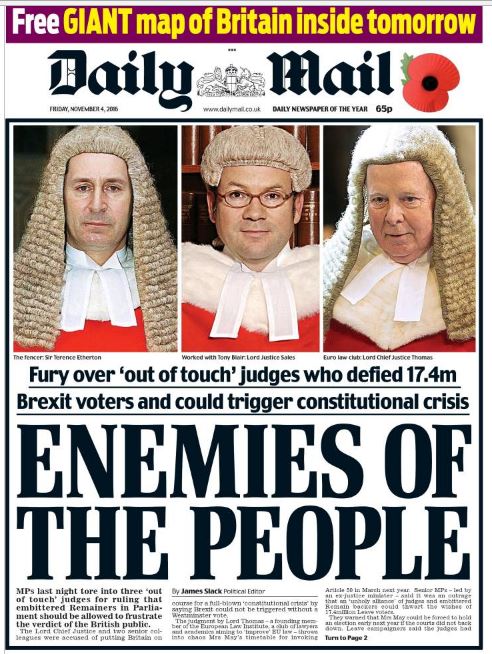

Chapter 8: The Single Perspective Instinct

We live in a world in which many people have strong opinions. However, when these opinions are set into a single world view, we can become blind to any information which contradicts us. This is the problem of the single perspective instinct and it can make it very difficult to understand reality.

“Being always in favour of or always against any particular idea makes you blind to information that doesn’t fit your perspective,” writes Rosling. “This is usually a bad approach if you like to understand reality.”

The single perspective instinct can be alluring. It is the preference for simple explanations and simple solutions to the world’s problems, but life is somewhat more complicated. This single cause and solution view creates a completely warped view of the world.

There are two main reasons why we do this: professional and political bias. Professionals will always see the world from the perspective of their own expertise. A hammer will see everything as a nail and will probably adopt the same approach. Even experts in their field can be wrong.

A poll of women’s rights activists found that only 8% realised that 30-year-old women have spent only one year less in school on average than men. They were so intent on seeing the situation as bad that they ignored the progress their own efforts have brought about.

He warns against relying the media to form a world view. It’s like forming an impression of a person just from his or her feet. The foot is far from the most attractive part of the body, so it doesn’t give you a fair representation of the rest of the person.

In the same way, the media tends to present the worst of the world; the disasters, the catastrophes and the crime. If you form your world view based on media reports, you’ll imagine the situation is much worse than it actually is.

Campaigners often paint the world as getting worse, but they are not aware that progress happening. If they ditched the attitude that things are only getting worse, they could garner more support for their cause.

People love the idea of being able to point to a single cause and single solution. For example, many use numbers to illustrate all sorts of issues, but they do not always represent the best solution. They do not help you to understand the reality behind them.

He recalls a conversation with the Prime Minister of Mozambique who said he believed the economy was making progress. Rosling argued that the data did not show this, but the Prime Minister replied that he did not solely rely on numbers to measure progress. He’d look at the shoes people wore and construction projects taking place. If the shoes were old, it meant that people didn’t have money to replace them. If construction projects were overgrown with grass, it suggested there wasn’t enough money being invested.

There is never a single explanation to any situation. It limits your imagination. Factfulness is realising the limitations of this perspective and finding ways to view situations from a wider range of viewpoints. This will help people to develop a more accurate understanding of the world they live in and to challenge their own world views.

Chapter 9: The Blame Instinct

We live in a culture which loves to apportion blame. This instinct assigns a clear cause to an event and finds someone who was at fault.

It’s a comforting approach. When things go wrong it is nice to think it’s because of bad people with bad intentions, but that seldom tells the entire story. We attach a lot of importance to individual groups or people, but it also stops us from understanding the world.

Once we find someone to blame, we stop looking for the actual cause of the problem and focus on punishing the person we think is at fault. The result is that we’re unable to prevent it from happening again.

For example, we might want to blame a plane crash on a pilot who falls asleep, but this does not stop another pilot from falling asleep in the future. Instead we should be looking at why the pilot fell asleep in order to stop it from happening again.

Hand in hand with the blame instinct comes the tendency to credit someone for an achievement even if the reality is more complicated. Someone has to take the blame or be given the credit. We love to point fingers if it confirms our belief

Even Rosling himself is not immune. When UNICEF hired him to investigate a company given a contract for malaria drugs, he became convinced that the company was acting improperly. Even before he finished his investigation, he started pointing fingers. In reality, the company was honest but simply had an innovative business model.

The same principle is at work when looking at the number of immigrants killed trying to cross the sea into Europe. It is common to blame the smugglers who traffic these people across the sea in small craft which are routinely dangerously overloaded. In reality, though, the problem is Europe’s immigration policies which state that an airline which brings illegal immigrants into the country will have to pay for their repatriation.

Airlines will not be able to tell if someone is truly an illegal immigrant in the few minutes they have before they board a flight, so they will ban anyone who doesn’t have a Visa. This means that refugees who have a right to enter Europe under the Geneva Convention cannot do so by any legitimate means. They are forced into the hands of the smugglers thanks to official European policy.

Any boats which bring refugees by sea are confiscated by the authorities which is why smugglers turn to cheap dinghies because they cannot afford to lose a larger boat.

On the other hand, we can also be in a rush to give credit to a single person or law. China’s low birth rate is accredited to Mao’s single child policy, but rates had started to fall before the law came into force. Instead the decline was down to institutions and technology that were in place.

Factfulness is the ability to recognise when someone is being scapegoated and to understand that this stops people creating viable solutions for the future. It is easy to look for a clear solution when something bad happens, but it stops us developing a fact-based view of the world and coming up with a solution which actually works.

Chapter 10: The Urgency Instinct

Rosling’s tenth and final instinct is one which can bring all the others to the fore: the tendency to take urgent action to solve a problem. While this might have served us well in the past, it can cause us to make rash decisions based on incomplete information.

The urgency instinct is embedded in our evolution, and in times gone by, it has served us very well. For example, if you think there is a lion in the grass you don’t want to spend time analysing your options; you simply need to start running. It’s always the safest option.

It can also be useful today. If you’re driving and someone slams on the brakes, you’ll have to take drastic action to avoid a crash. However, in today’s modern world, it can often create problems.

While Rosling was a doctor in Mozambique, a disease broke out that paralysed patients within minutes and sometimes caused blindness. He wasn’t certain that it was infectious, but the Mayor didn’t wait to find out. He ordered the military to set up roadblocks to prevent busses reaching the city. To get around these roadblocks, women asked fishermen to take them to the city by sea. It was a dangerous journey and many of these boats were overloaded. They capsized and causes the deaths of women and children.

After some research they discovered the root cause was eating processed Cassava. So, while the Mayor believed his prompt action was the safest approach, it actually caused a number of deaths which should have been avoided.

The principal of ‘now or never’, causes people to conjure a worst-case scenario. It kills the ability to think things through and encourages bad decision making. This is why salespeople come up with limited time offers. They are giving you a deadline and introducing a sense of urgency into your decision making in the hope you’ll be rushed into making a purchase.

To compel people to taking action, activists will often try to trigger the urgency instinct. They will stress how urgent a problem is and paint a worst-case scenario of what will happen if you don’t do something now. However, Rosling believes this is counterproductive.

Fear and exaggerated data can numb people to the risks campaigners are warning about which can lead to complacency and inaction.

For example, most countries say they are committed to fighting a climate change but aren’t tracking their progress. It begs the question: how can they truly fight climate change if they are not tracking their progress?

Rosling tells us that the world faces five serious risks: global pandemic, financial collapse, world war, climate change and extreme poverty. The first two have happened before while the second two are happening now.

They need to be approached with cool heads and data analysis rather than sparking fear and urgency. It’s about crying wolf. It can lead to these risks being ignored despite the dreadful consequences. We must worry about the right thing.

The idea of factfulness is to remember that things might not be as urgent as they seem. If you’re afraid and under pressure to act quickly, you are likely to make bad decisions. We must take a breath, take action based on data and be very wary of fortune tellers who insist they know what’s going to happen. Although the world’s problems need to be solved it is not always a good idea to take urgent or drastic measures.

Chapter 11: Factfulness in Practice

The final chapter brings everything together and demonstrates how all the lessons explained so far can be put to practical use. We see each of the ten instincts on show and how factfulness can lead to truly positive real-world solutions.

To demonstrate, Rosling takes us to a remote village in the DRC. He had travelled there to investigate a disease which was caused by eating unprocessed Cassava. The villagers believed he was collecting their blood to sell it and they were angry.

All the instincts discussed in this book were on display. The sharp needles and blood had triggered the fear instinct. The generalisation instinct made them categorise him as a plundering white man. Blame instinct caused them to assume he had malicious intent and the urgency instinct convinced them they had to act immediately, in this case by threatening him with machetes.

Things might have worked out very badly for both him and his translator if it hadn’t been for an old woman who successfully calmed the crowd down and explained that he was trying to help them. Although she was illiterate, she was bringing all the core principles of factfulness to bear in a very dangerous situation. As such, she managed to save both their lives.

In the same way we can bring it to our daily lives, in business, education and journalism and communities. Children should be taught to adopt a fact-based approach to life which will help them to develop a better view of the world and create better solutions. Children should be taught to be curious, to hold two different ideas at the same time. They should be willing to alter their opinions with new facts. This will protect them from ignorance.

Having a typo in your CV can keep you from getting a top job. However, people who make policies are placing a billion people in the wrong continent. Businesses have distorted world views and fail to understand that markets are growing in Africa and Asia. Being an American company is no longer a privilege which will automatically attract employees and customers. If investors relinquish their preconceptions about Africa, they may realise that it contains some of the best business opportunities in the world.

With a more factful attitude, journalists may become aware of their dramatic world views and present something more accurate and useful. However, it is a bit of a stretch to expect them to truly embrace all the principles of factfulness and start reporting the mundane alongside the unusual. The onus is on people to learn how to consume news in a more factful manner.

If you are ignorant at the global level there’s a good chance you’ll also be ignorant at the local level within your own community, company or organisation. They are all using erroneous data to manage their businesses and prepare for disasters.

Leaders in companies, cities, countries and organisations should carry out fact-based surveys to uncover ignorance within their organisations. Only by doing so can they develop a more accurate and realistic world view. Factfulness can be put into practice in all our daily lives, at home at work and in our communities.