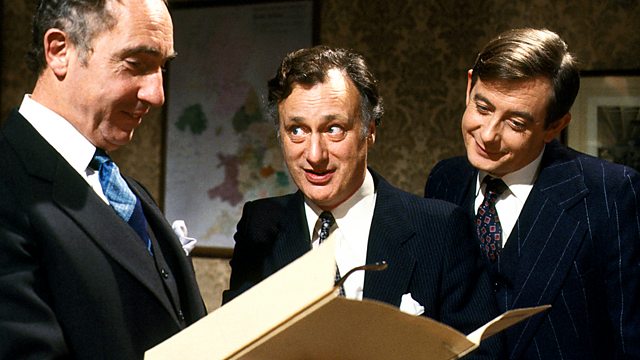

Jay Lynn on “Yes, Minister”

Jay Lynn on “Yes, Minister”

The fallacy that public choice economics took on was the fallacy that government is working entirely for the benefit of the citizen. And this was reflected by showing that in any, that in the programme, in Yes Minister, we showed that almost everything that the government has to decide is a conflict between two lots of private interests: that of the politicians and that of the civil servants trying to advance their own careers and improve their own lives. And that’s why public choice economics, which explains why this was going on, was at the root of almost every episode of Yes Minister and Yes, Prime Minister.

Party Games

Party Games

Sir Humphrey: So we trust you to make sure that your minister does nothing incisive or divisive over the next few weeks.

Sir Arnold: Avoids anything controversial.

Sir Humphrey: Expresses no firm opinion about anything at all. Now, is that quite clear?

Bernard: Yes, well, I think that’s probably what he was planning to do anyway.

The Whisky Priest

Sir Humphrey: Bernard, I have served eleven governments in the past thirty years. If I had believed in all their policies, I would have been passionately committed to keeping out of the Common Market, and passionately committed to going into it. I would have been utterly convinced of the rightness of nationalising steel, and of denationalising it and renationalising it. On capital punishment, I’d have been a fervent retentionist and an ardent abolitionist. I would have been a Keynesian and a Friedmanite, a grammar school preserver and destroyer, a nationalisation freak and a privatisation maniac, but above all, I would have been a stark staring raving schizophrenic!

The Middle-Class Rip-Off

Sir Humphrey: Bernard, subsidy is for art… for culture. It is not to be given to what the people want: it is for what the people don’t want but ought to have!

The Moral Dimension

The Moral Dimension

Hacker: Bernard, any messages?

Bernard: Well, there is one for Sir Humphrey, Minister.

Sir Humphrey: Oh good.

Bernard: Yes, the Soviet embassy’s on the line, Sir Humphrey: a Mr Smirnoff.

The Bed of Nails

Bernard: The Department of Employment lobbies for the TUC, whereas the Department of Industry lobbies for the employers. It’s rather a nice balance. Energy lobbies for the oil companies, Defence lobbies for the armed forces, the Home Office lobbies for the police and so on.

Hacker: So the whole system is designed to stop the Cabinet from carrying out its policies?

Bernard: Well, somebody’s got to.

Hacker: Would you be surprised, for instance, if a British aircraft carrier turned up in the Central African Republic?

Sir Humphrey: Well, I for one, Minister, would be very surprised: it’s a thousand miles inland.

The Skeleton in the Cupboard

Sir Humphrey: If local authorities don’t send us the statistics that we ask for, then government figures will be a nonsense.

Hacker: Why?

Sir Humphrey: They will be incomplete.

Hacker: But government figures are a nonsense anyway.

Bernard: I think Sir Humphrey wants to ensure they are a complete nonsense.

Sir Humphrey: The identity of the official whose alleged responsibility for this hypothetical oversight has been the subject of recent discussion is not shrouded in quite such impenetrable obscurity as certain previous disclosures may have led you to assume, but, not to put too fine a point on it, the individual in question is, it may surprise you to learn, one whom your present interlocutor is in the habit of defining by means of the perpendicular pronoun.

The Challenge

The Challenge

Hacker: But the broad strategy is to cut ruthlessly at waste while leaving essential services intact.

Ludovic Kennedy: Well, that is what your predecessor said. Are you saying that he failed?

Hacker: Please, let me finish, because we must be absolutely clear about this, and I would be quite frank with you. The plain fact of the matter is that at the end of the day it is the right, no the duty, of the elected government in the House of Commons to ensure that government policy, the policies on which we were elected and for which we have a mandate, the policies after all for which the people voted, are the policies which finally when the national cake has been divided up, and may I remind you we as a nation don’t have unlimited wealth, so we can’t pay ourselves more than we’ve earned, are the policies… I’m sorry, what was the question again?

A Question of Loyalty

A Question of Loyalty

Betty Oldham: Look, Sir Humphrey, whatever we ask the Minister, he says is an administrative question for you, and whatever we ask you, you say is a policy question for the Minister. How do you suggest we find out what’s going on?

Sir Humphrey: Yes, yes, yes, I do see that there is a real dilemma here. In that, while it has been government policy to regard policy as a responsibility of ministers and administration as a responsibility of officials, the questions of administrative policy can cause confusion between the policy of administration and the administration of policy, especially when responsibility for the administration of the policy of administration conflicts, or overlaps with, responsibility for the policy of the administration of policy.

Betty Oldham: Well, that’s a load of meaningless drivel… isn’t it?

Sir Humphrey: It’s not for me to comment on government policy. You must ask the Minister.

Equal Opportunity

Equal Opportunity

Sir Humphrey: It takes time to do things NOW!

Hacker: The three articles of civil service faith — it takes longer to do things quickly, it is more expensive to do them cheaply and it is more democratic to do them in secret!

Sir Humphrey: Now, Minister, if you are going to promote women just because they’re the best person for the job, you will create a lot of resentment throughout the whole of the Civil Service!

Sir Humphrey: We’re quite well up to establishment on typists and cleaners and tea ladies. Any ideas, Bernard?

Bernard: Well, we are a bit short on temporary secretaries.

Hacker: I’m talking about Permanent Secretaries.

Sir Humphrey: Permanent Secretaries?

Hacker: We need some female mandarins.

Bernard: Sort of, satsumas… Minister?

Open Government

Open Government

The Right to Know

The Right to Know