Rental car agreements = exposure to Chrysler products but there was a problem! Chrysler was not selling cars to Hertz and Avis (car rental companies in the US) but leasing them and then subsequently buying those vehicles and selling them as used. The used-car losses at Chrysler were $88 million in the first year Iacocca took over (1979/1980). The change Lee Iacocca implemented was to sell models to Hertz and Avis at a lower margin so that Hertz and Avis had to deal with selling the used cars. In the process, Hertz customers get to try out the Chrysler vehicles.

Rental car agreements = exposure to Chrysler products but there was a problem! Chrysler was not selling cars to Hertz and Avis (car rental companies in the US) but leasing them and then subsequently buying those vehicles and selling them as used. The used-car losses at Chrysler were $88 million in the first year Iacocca took over (1979/1980). The change Lee Iacocca implemented was to sell models to Hertz and Avis at a lower margin so that Hertz and Avis had to deal with selling the used cars. In the process, Hertz customers get to try out the Chrysler vehicles.

Tag Archives: Ford Motor Company

Lee Iacocca: A Company Needs A System Of Financial Controls

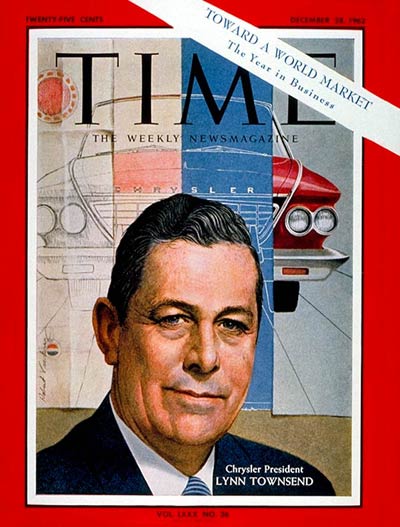

In late 1979, when Iacocca dived deeper into understanding Chrysler, he realized that nobody in the company fully understood what was going on in terms of finances and projections. Finding out the return on investment for each plant was rather difficult because no one took responsibility at Chrysler. Lynn Townsend ran Chrysler and according to Iacocca, he focused on oversea expansion (to enhance the companies valuation) rather than quality vehicles at home. Townsend aggressively expanded in Europe and in the process made himself very wealthy but Iacocca maintains that Townsend did not understand the fundamentals of the car business. That was because Townsend was a banker. So much so that Chrysler was running a marginal or losing operation around the world.

In late 1979, when Iacocca dived deeper into understanding Chrysler, he realized that nobody in the company fully understood what was going on in terms of finances and projections. Finding out the return on investment for each plant was rather difficult because no one took responsibility at Chrysler. Lynn Townsend ran Chrysler and according to Iacocca, he focused on oversea expansion (to enhance the companies valuation) rather than quality vehicles at home. Townsend aggressively expanded in Europe and in the process made himself very wealthy but Iacocca maintains that Townsend did not understand the fundamentals of the car business. That was because Townsend was a banker. So much so that Chrysler was running a marginal or losing operation around the world.

This is a synopsis & analysis based on Iacocca: An Autobiography and other miscellaneous research sources. Enjoy.

This is a synopsis & analysis based on Iacocca: An Autobiography and other miscellaneous research sources. Enjoy.

Lee Iacocca: Be Careful Of Which Job You Choose

On November 2, 1978, Lee joined Chrysler and on the very same day, the company announced a 3rd quarter loss of almost $160 million, the worst deficit in its history. The organizational structure alone made Iacocca cringe. Chrysler was structured as a cluster of smaller departments loosely connected to the center. There was no system of meetings to get different parts of the company in order to regularly communicate with each other. Chrysler needed to embrace the idea of Newton’s Third Law of Motion – that every action has an equal and opposite reaction. The engineers failed to interact with the manufacturing division so they were not able to understand how a product could work. Manufacturing and engineering need to work together. Riccardo and Bill McGagh the treasurer were constantly running from bank to bank in order to ensure that the Chrysler loans were intact. Even worse, the Chrysler cars were lousy, the morale was bad and the factories were deteriorating. If Iacocca had known all this going in, he would not have joined Chrysler as its CEO.

On November 2, 1978, Lee joined Chrysler and on the very same day, the company announced a 3rd quarter loss of almost $160 million, the worst deficit in its history. The organizational structure alone made Iacocca cringe. Chrysler was structured as a cluster of smaller departments loosely connected to the center. There was no system of meetings to get different parts of the company in order to regularly communicate with each other. Chrysler needed to embrace the idea of Newton’s Third Law of Motion – that every action has an equal and opposite reaction. The engineers failed to interact with the manufacturing division so they were not able to understand how a product could work. Manufacturing and engineering need to work together. Riccardo and Bill McGagh the treasurer were constantly running from bank to bank in order to ensure that the Chrysler loans were intact. Even worse, the Chrysler cars were lousy, the morale was bad and the factories were deteriorating. If Iacocca had known all this going in, he would not have joined Chrysler as its CEO.

This is a synopsis & analysis based on Iacocca: An Autobiography and other miscellaneous research sources. Enjoy.

This is a synopsis & analysis based on Iacocca: An Autobiography and other miscellaneous research sources. Enjoy.

Lee Iacocca: Don’t Elaborate Much On Your Deadly Mistakes

In his autobiography, Iacocca slips in a small discussion of the Fort Pinto. The Ford Pinto was infamous for having been a deadly vehicle in the case of a rear-end accident. If struck from behind, it would burst into flames within seconds. The problem was that the fuel tank was behind the axle + the filler neck on the fuel tank would rip out on impact and then would spill or spray raw gas out. Perfect for starting a fire. In 1971, for $2,000, the Pinto was an affordable compact.

In his autobiography, Iacocca slips in a small discussion of the Fort Pinto. The Ford Pinto was infamous for having been a deadly vehicle in the case of a rear-end accident. If struck from behind, it would burst into flames within seconds. The problem was that the fuel tank was behind the axle + the filler neck on the fuel tank would rip out on impact and then would spill or spray raw gas out. Perfect for starting a fire. In 1971, for $2,000, the Pinto was an affordable compact.

Joan Claybrook (one of Ralph Nader’s protégés) believed that the Pinto was not an engineering problem but a PR disaster in the making. Internal memos at Ford have been exposed with having weighed the safety risks over the cost saving for customers. Despite the famous Pinto 1973 memorandum, Iacocca denies this stating: “there is no truth to charge that we tried to save a few bucks and knowingly made a dangerous car” (162, Autobiography). Ford voluntarily recalled 1.5 million Pintos in June of 1978, a month before Iacocca was fired.

Joan Claybrook (one of Ralph Nader’s protégés) believed that the Pinto was not an engineering problem but a PR disaster in the making. Internal memos at Ford have been exposed with having weighed the safety risks over the cost saving for customers. Despite the famous Pinto 1973 memorandum, Iacocca denies this stating: “there is no truth to charge that we tried to save a few bucks and knowingly made a dangerous car” (162, Autobiography). Ford voluntarily recalled 1.5 million Pintos in June of 1978, a month before Iacocca was fired.

The Ford Pinto Memorandum

The following figures are drawn from the 1973 memorandum* written for and circulated amongst senior management at the Ford Motor Company concerning cost-benefit analysis of retrofitting or altering production of autos and light trucks susceptible to fires from leaking gas tanks after a hypothetical roll-over.

Fatalities Associated with Roll-Over-Induced Fuel Leakage and Fires

Expected Costs of producing all US cars and light trucks with fuel tank modifications:

- Expected unit sales: 12.5 million vehicles (includes 11 million cars and 1.5 million light utility vehicles built on same chassis)

- Modification costs per unit: $11.00

- Total Cost: $137.5 million

[= 12,500,000 vehicles x $11.00 per unit]

Expected Costs of producing vehicles without fuel tank modifications:

- Expected accident results (assuming 2100 accidents): 180 burn deaths 180 serious burn injuries 2100 burned out vehicles

- Unit costs of accident results (assuming out of court settlements): $200,000 per burn death** $67,000 per serious injury $700 per burned out vehicle

- Total Costs: $49.53 million

[= (180 deaths x $200k) + (180 injuries x $67k) + (2100 vehicles x $700 per vehicle)]

Thus, the costs for fixing the roll-over problem was $137 million, while the computed cost of cases where injuries occur was only $50 million.

*”Fatalities Associated With Crash Induced Fuel Leakage and Fires,” by E.S. Grush and C.S. Saundy, Environmental and Safety Engineering.

**By the way, the $200k and $67k figures for the average value of a lost or injured adult life is drawn from the NHTSA (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration) calculation of the estimated costs to society of automobile accidents. It is not a low-ball figure fabricated by Ford. (For example, the $200k for death was calculated by adding estimated direct costs of $163k — such as loss of future earnings, plus $37k of indirect costs — such as hospital and insurance costs, legal and court costs, victim pain and suffering, funeral costs, and property damage.) This is the calculation typically used by the U.S. Federal government for performing cost-benefit analyses of highway construction projects (e.g. determining how safely we should build our roads and highways). Even today, such figures are commonly used by many state and local, as well as federal, government agencies to weigh costs of various tax-supported programs.

Continue reading Lee Iacocca: Don’t Elaborate Much On Your Deadly Mistakes

There Are Two Ways To Make Money

In 1970, Iacocca was made president of Ford Motor Company ie. head of 432,000 employees with a payroll of $3.5 billion, with over 2.5 million cars and 750,000 trucks produced per year. Overseas production was an additional 1.5 million vehicles. Total sales in 1970 were $14.9 billion with a profit of $515 million. According to Iacocca, there are two ways to make a profit.

In 1970, Iacocca was made president of Ford Motor Company ie. head of 432,000 employees with a payroll of $3.5 billion, with over 2.5 million cars and 750,000 trucks produced per year. Overseas production was an additional 1.5 million vehicles. Total sales in 1970 were $14.9 billion with a profit of $515 million. According to Iacocca, there are two ways to make a profit.

(1) sell more goods or 2) spend less on overhead.

It is always easier to cut spending in the name of efficiency than to increase sales. For example, Iacocca cut 4 problem spots down by $50 million in a) timing foul-ups, b) product complexity, c) design costs, and d) outmoded business practices. There was room for improvement in switching production from one vehicle to another at Ford plants, which usually took 2 weeks. By 1974, conversion times were down to a weekend through computer programming. Iacocca attacked freight spending as well, which had only a small percentage of the total expenses, but was at over $500 million a year. Under Iacocca, freight cars were much more tightly packed, a few millimeters meant the difference between packing a car or paying to ship air (ie. space). Iacocca closed down the appliance side of Ford, which made laundry machines that were not competitive within that industry.

Another more personal example of analyzing spending was in the Glass House (Ford HQ). Henry Ford II loved the Glass House cafeteria hamburgers because he could not get anything like it anywhere else and so Iacocca investigated with the head chef how Henry Ford’s hamburgers were made so delectable. The chef showed Iacocca the process revealing that these hamburgers were actually grinded down New York strip steaks shaped it into patties. Waste was abundant at Ford. The lunches in the cafeteria cost $2.00 per day, but that was after tax spending for each management executive. Everyone in the cafeteria was in the 90% bracket of the 1960s era taxation so $2.00 meant you had to earn $20.00 to pay for that hamburger since 0.90 x $20.00 = $18.00 which went to the government. Iacocca conducted a study of the cafeteria and determined that the cost per head was $104 per day. Cutting costs would earn respect with the bean counters of the company.

Another more personal example of analyzing spending was in the Glass House (Ford HQ). Henry Ford II loved the Glass House cafeteria hamburgers because he could not get anything like it anywhere else and so Iacocca investigated with the head chef how Henry Ford’s hamburgers were made so delectable. The chef showed Iacocca the process revealing that these hamburgers were actually grinded down New York strip steaks shaped it into patties. Waste was abundant at Ford. The lunches in the cafeteria cost $2.00 per day, but that was after tax spending for each management executive. Everyone in the cafeteria was in the 90% bracket of the 1960s era taxation so $2.00 meant you had to earn $20.00 to pay for that hamburger since 0.90 x $20.00 = $18.00 which went to the government. Iacocca conducted a study of the cafeteria and determined that the cost per head was $104 per day. Cutting costs would earn respect with the bean counters of the company.