Written By Guest Academic Writers: Arie Vw, Ralph F, Sam B, Napur D, Adam Y.

Introduction

Professional football is a thriving business. Each Sunday, millions of fans flock to National Football League stadiums to see their favorite teams play. Millions more watch the games on television, which provides one of the largest advertising audiences for television networks. However, there are some groups which are marginalized by professional football. In particular, some Native Americans are offended that Washington’s team is named the “Redskins”. “Redskin” has been used as a racial slur to denigrate Native Americans as savage and uncultured. This has led many Native American groups to argue that it is unethical to use the name Redskin as the basis for a highly profitable business. Despite the controversy regarding the name, team owner Daniel Snyder has vowed “NEVER” to change the name.

Professional football is a thriving business. Each Sunday, millions of fans flock to National Football League stadiums to see their favorite teams play. Millions more watch the games on television, which provides one of the largest advertising audiences for television networks. However, there are some groups which are marginalized by professional football. In particular, some Native Americans are offended that Washington’s team is named the “Redskins”. “Redskin” has been used as a racial slur to denigrate Native Americans as savage and uncultured. This has led many Native American groups to argue that it is unethical to use the name Redskin as the basis for a highly profitable business. Despite the controversy regarding the name, team owner Daniel Snyder has vowed “NEVER” to change the name.

At any rate, this article argues that Snyder is just wrong. Using Redskins as a team name is unethical. And while the initial costs of the brand change are upfront and considerable, the new jersey and paraphernalia sales could generate a breakeven ROI within 3 to 7 years based on various estimates, back of napkin. But that’s not the point, to prove the ethical point, a careful identification of the ethical issues involved is necessary. Once identified, analysis of those issues using various ethical frame works will be conducted. Finally, an assessment of other relevant cases involving Native American imagery in sports will reinforce the position that the Redskins name should be changed.

Identification of the Ethical Issues

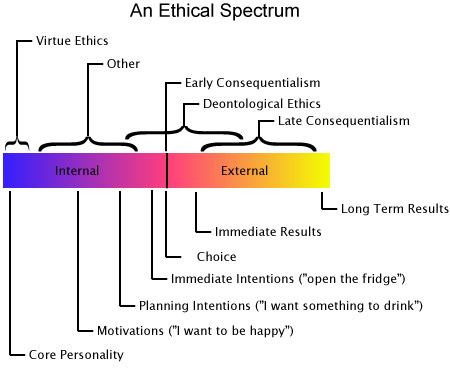

Business ethics is not black and white. There are grey areas which fall in between what is clearly right or clearly wrong. These grey areas form an ethical spectrum. At one side of this ethical spectrum are questions of legality, whether an action is allowed by law. At the other side of the spectrum are questions of whether an action is socially responsible. In order to clearly identify the ethical issues involved in the use of the name Washington Redskins, we will examine both ends of the spectrum before positioning the central ethical issue.

Business ethics is not black and white. There are grey areas which fall in between what is clearly right or clearly wrong. These grey areas form an ethical spectrum. At one side of this ethical spectrum are questions of legality, whether an action is allowed by law. At the other side of the spectrum are questions of whether an action is socially responsible. In order to clearly identify the ethical issues involved in the use of the name Washington Redskins, we will examine both ends of the spectrum before positioning the central ethical issue.

At one end of the ethical spectrum is the question of whether something is legal. At first glance it seems straightforward that the use of the name Redskins is legal since there is no law against it. However, the reality is more complicated. In order to profit from their name, the Washington Redskins need to be able to enforce their trademark. This is becoming difficult because of the recent decision in Blackhorse v Pro Football Inc.4 In Blackhorse, the United States Patent and Trademark Office found that the Redskins’ trademarks were disparaging of Native Americans and ordered them cancelled. While the Blackhorse decision is currently under appeal, the Redskins’ trademark is also under threat from Congress. The proposed Non-Disparagement of Native American Persons or Peoples in Trademark Registration Act, would effectively strip the Redskins of their trademarks.5 President Obama also came out in favour of changing the team name in 2013.6 Obama’s position is evidence of mounting pressure against the Redskins in the battle over their name. Thus, from the legal end of the ethical spectrum, the Washington Redskins name is controversial.

At one end of the ethical spectrum is the question of whether something is legal. At first glance it seems straightforward that the use of the name Redskins is legal since there is no law against it. However, the reality is more complicated. In order to profit from their name, the Washington Redskins need to be able to enforce their trademark. This is becoming difficult because of the recent decision in Blackhorse v Pro Football Inc.4 In Blackhorse, the United States Patent and Trademark Office found that the Redskins’ trademarks were disparaging of Native Americans and ordered them cancelled. While the Blackhorse decision is currently under appeal, the Redskins’ trademark is also under threat from Congress. The proposed Non-Disparagement of Native American Persons or Peoples in Trademark Registration Act, would effectively strip the Redskins of their trademarks.5 President Obama also came out in favour of changing the team name in 2013.6 Obama’s position is evidence of mounting pressure against the Redskins in the battle over their name. Thus, from the legal end of the ethical spectrum, the Washington Redskins name is controversial.

The other end of the ethical spectrum involves whether an action is socially responsible. The Washington Redskins have taken some steps towards fulfilling their social responsibility as a business. The team plays an important role in their local community through the Washington Redskins Charitable Foundation and also helps Native American groups through their Original Americans Foundation.7 However, the Redskins’ philanthropy is controversial. Several Native American groups have refused their money because they do not want to be associated with what they regard as a racial slur.8 Determining whether the team name is right from a social responsibility perspective involves weighing the good of these charitable contributions against the harm done to Native Americans who are marginalized and stereotyped by the term Redskin.

The other end of the ethical spectrum involves whether an action is socially responsible. The Washington Redskins have taken some steps towards fulfilling their social responsibility as a business. The team plays an important role in their local community through the Washington Redskins Charitable Foundation and also helps Native American groups through their Original Americans Foundation.7 However, the Redskins’ philanthropy is controversial. Several Native American groups have refused their money because they do not want to be associated with what they regard as a racial slur.8 Determining whether the team name is right from a social responsibility perspective involves weighing the good of these charitable contributions against the harm done to Native Americans who are marginalized and stereotyped by the term Redskin.

The central business ethics issue is whether it is right to profit from the use of the term Redskin. This involves elements from both the legal and social responsibility sides of the ethical spectrum. However, whether it is ethical to use the term Redskin for profit affects many agents beyond the wealthy Caucasian team owners. Actors such as sponsors, television networks, and merchandise providers profit indirectly from the team name. Players, coaches, equipment staff, and referees create the product that the team sells. Fans across the country provide the demand for the team’s services and ensure there is a market for sponsors and advertisers to tap into. Each of these individuals is involved as an agent in the ethical decision of whether it is right to profit from the term Redskin. Since there are so many agents involved, the ethical issue is very complex and requires careful analysis.

The central business ethics issue is whether it is right to profit from the use of the term Redskin. This involves elements from both the legal and social responsibility sides of the ethical spectrum. However, whether it is ethical to use the term Redskin for profit affects many agents beyond the wealthy Caucasian team owners. Actors such as sponsors, television networks, and merchandise providers profit indirectly from the team name. Players, coaches, equipment staff, and referees create the product that the team sells. Fans across the country provide the demand for the team’s services and ensure there is a market for sponsors and advertisers to tap into. Each of these individuals is involved as an agent in the ethical decision of whether it is right to profit from the term Redskin. Since there are so many agents involved, the ethical issue is very complex and requires careful analysis.

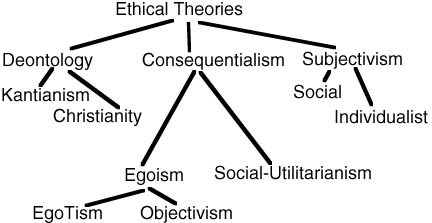

Analysis of the Ethical Issues

In order to come to a clear decision on the ethical issues associated with the use of the name Washington Redskins, one should think about the issue systematically using ethical frameworks. Ethical frameworks are models for thinking about ethical issues and determining the right course of action. These frameworks include utilitarianism, Rawlsian liberalism, deontological and virtue-based reasoning, consequentialism, end-statism, and contractarianism. While many of these ethical frameworks lead to the same conclusion, they take different routes to get to that conclusion. Understanding why the frameworks follow different paths requires delving deeper into each one.

In order to come to a clear decision on the ethical issues associated with the use of the name Washington Redskins, one should think about the issue systematically using ethical frameworks. Ethical frameworks are models for thinking about ethical issues and determining the right course of action. These frameworks include utilitarianism, Rawlsian liberalism, deontological and virtue-based reasoning, consequentialism, end-statism, and contractarianism. While many of these ethical frameworks lead to the same conclusion, they take different routes to get to that conclusion. Understanding why the frameworks follow different paths requires delving deeper into each one.

The first ethical framework to look at is Contractarianism. Contractarianism holds that the right thing to do is to honour one’s agreements.9 Actions which lead to the breaking of an agreement are unethical. This approach is sound because society needs people to honour their agreements in order to function properly. Contractarianism is an ethical framework team owner Daniel Snyder could use to justify keeping the Redskins name as is. Washington has explicit contracts with sponsors including FedEx, Nike, NRG, Bank of America, and Coca-Cola which it entered into on the basis that the team nickname would be the Redskins.10 In addition, there is an implicit contract which has been made with fans. In return for their loyalty, ticket purchases, and merchandise spending, the team promises fans pride and a sense of belonging with “their” Redskins. By changing the name or aspects of the team’s tradition, the Redskins would be violating an unspoken premise of these agreements, that they would indeed be called the Redskins. Consequently, a limited contractarian perspective would suggest changing the name is unethical.

The first ethical framework to look at is Contractarianism. Contractarianism holds that the right thing to do is to honour one’s agreements.9 Actions which lead to the breaking of an agreement are unethical. This approach is sound because society needs people to honour their agreements in order to function properly. Contractarianism is an ethical framework team owner Daniel Snyder could use to justify keeping the Redskins name as is. Washington has explicit contracts with sponsors including FedEx, Nike, NRG, Bank of America, and Coca-Cola which it entered into on the basis that the team nickname would be the Redskins.10 In addition, there is an implicit contract which has been made with fans. In return for their loyalty, ticket purchases, and merchandise spending, the team promises fans pride and a sense of belonging with “their” Redskins. By changing the name or aspects of the team’s tradition, the Redskins would be violating an unspoken premise of these agreements, that they would indeed be called the Redskins. Consequently, a limited contractarian perspective would suggest changing the name is unethical.

A broader contractarian perspective might suggest it would be ethical to change the Washington Redskins name. In addition to their agreements with sponsors and fans, the Washington Redskins also need to consider their social contract as a business. Society has an implicit contract with every business that the business will act responsibly and not cause harm.11 The purpose of this social contract is to protect the most vulnerable individuals from unfettered greed. Native Americans are a particularly vulnerable group within society because of the legacy of colonialism. By choosing a name which (arguably) demeans Native Americans, the Washington Redskins have violated the social contract. As a result, an expansive understanding of contractarianism would find it unethical to keep the team name as is.

A broader contractarian perspective might suggest it would be ethical to change the Washington Redskins name. In addition to their agreements with sponsors and fans, the Washington Redskins also need to consider their social contract as a business. Society has an implicit contract with every business that the business will act responsibly and not cause harm.11 The purpose of this social contract is to protect the most vulnerable individuals from unfettered greed. Native Americans are a particularly vulnerable group within society because of the legacy of colonialism. By choosing a name which (arguably) demeans Native Americans, the Washington Redskins have violated the social contract. As a result, an expansive understanding of contractarianism would find it unethical to keep the team name as is.

The next ethical framework to look at is Utilitarianism. Utilitarianism involves deciding upon the greatest good for the greatest number of people.12 Actions are right if they advance the greatest good for the greatest number and wrong if they do not. The problem with utilitarianism is that it is difficult to determine what the greatest good for the greatest number actually is. In the case of the Washington Redskins, polls show that a majority of the team’s fans want to keep the team name as is.13 This suggests fans are concerned about losing the value they get from the Redskins’ traditions if the name is changed. Furthermore, there are significant commercial gains for sponsors and ownership from keeping the name since tradition is one of the key drivers of Redskins merchandise and memorabilia sales. This suggests keeping the name results in the greatest good for the greatest number, making it the ethical choice from a utilitarian perspective.

The next ethical framework to look at is Utilitarianism. Utilitarianism involves deciding upon the greatest good for the greatest number of people.12 Actions are right if they advance the greatest good for the greatest number and wrong if they do not. The problem with utilitarianism is that it is difficult to determine what the greatest good for the greatest number actually is. In the case of the Washington Redskins, polls show that a majority of the team’s fans want to keep the team name as is.13 This suggests fans are concerned about losing the value they get from the Redskins’ traditions if the name is changed. Furthermore, there are significant commercial gains for sponsors and ownership from keeping the name since tradition is one of the key drivers of Redskins merchandise and memorabilia sales. This suggests keeping the name results in the greatest good for the greatest number, making it the ethical choice from a utilitarian perspective.

Utilitarianism is actually more complex than a simple counting of numbers of people who would be benefited or harmed by an action. One also has to weigh the size of the benefits or harms to each person. There are very substantial costs to Native Americans from the use of the term Redskin. Redskin perpetuates the myth that Native Americans are somehow different and inferior to whites. Certainly legally different in terms of treaty rights in Canada and the US in some cases for example. The use of the term in professional sports makes racism seem socially acceptable, if we believe that Redskin is a racist term. The harm from this stereotype is impossible to quantify since it affects some Native Americans more than others. As a result, a utilitarian approach to the ethical issue of the Washington Redskins name is ultimately inconclusive because one cannot tell whether keeping the name represents the greatest good for the greatest number.

Utilitarianism is actually more complex than a simple counting of numbers of people who would be benefited or harmed by an action. One also has to weigh the size of the benefits or harms to each person. There are very substantial costs to Native Americans from the use of the term Redskin. Redskin perpetuates the myth that Native Americans are somehow different and inferior to whites. Certainly legally different in terms of treaty rights in Canada and the US in some cases for example. The use of the term in professional sports makes racism seem socially acceptable, if we believe that Redskin is a racist term. The harm from this stereotype is impossible to quantify since it affects some Native Americans more than others. As a result, a utilitarian approach to the ethical issue of the Washington Redskins name is ultimately inconclusive because one cannot tell whether keeping the name represents the greatest good for the greatest number.

Utilitarianism is not the only ethical framework which is inconclusive on whether it is right to profit from the use of the term Redskin. Consequentialism is a philosophy that involves looking at the consequences of actions. If the consequences of an action are good then that action is ethical. The critical question then becomes: consequences for whom? The Washington Redskins name may have negative consequences for Native Americans who feel marginalized and insulted by the term. However, there may be positive consequences for owner Daniel Snyder in keeping the name and continuing to make lots of money. As a result, unless we clearly determine what lens we are going to use, a consequentialist perspective is not very helpful to determining if keeping the name is right or wrong.

Utilitarianism is not the only ethical framework which is inconclusive on whether it is right to profit from the use of the term Redskin. Consequentialism is a philosophy that involves looking at the consequences of actions. If the consequences of an action are good then that action is ethical. The critical question then becomes: consequences for whom? The Washington Redskins name may have negative consequences for Native Americans who feel marginalized and insulted by the term. However, there may be positive consequences for owner Daniel Snyder in keeping the name and continuing to make lots of money. As a result, unless we clearly determine what lens we are going to use, a consequentialist perspective is not very helpful to determining if keeping the name is right or wrong.

End-statism is similar to consequentialism because it assesses whether an action is ethical by looking at the end result. Thus the individual steps necessary to get to the end result do not matter in the ultimate calculations.15 For the Washington Redskins, the scope of the end state is unclear. If the scope is limited to the owner then the end state is a highly profitable football team. This is a positive outcome and suggests it is right to keep the name as is. Likewise, the scope of

End-statism is similar to consequentialism because it assesses whether an action is ethical by looking at the end result. Thus the individual steps necessary to get to the end result do not matter in the ultimate calculations.15 For the Washington Redskins, the scope of the end state is unclear. If the scope is limited to the owner then the end state is a highly profitable football team. This is a positive outcome and suggests it is right to keep the name as is. Likewise, the scope of

the end state is the fans, then the end state includes the positive outcome of the joy of celebrating the Redskins’ tradition and watching their football games. However, if the end state includes Native Americans who are disenfranchised and oppressed as a result of the racial stereotypes that the name perpetuates then the end state is very negative. Without knowing which end state to look at, we cannot know whether the Washington Redskins name is ethical from an end-statist perspective.

While utilitarianism, end-statism and consequentialism may be inconclusive, there are also other ethical frameworks to consider. Deontological reasoning tests the ethical validity of an action by asking what the world would look like if everyone were to do so all the time.16 This universalization manoeuvre is best illustrated by assessing whether it is right to let your dog poop in a park and not clean up the mess. If everyone did this the world would literally be a crappy place. This means the right thing to do is to clean up the mess. Deontological reasoning is thus a clear and unambiguous ethical framework from which to judge an action.

Deontological reasoning would not support keeping the Washington Redskins name as is. Applying the universalization manoeuvre, we ask ourselves: What if every sports team had a racially offensive name that perpetuated racist behaviour throughout society? Would this be a pleasant world to live in? The answer to this question is clearly no. A society with more racial prejudice would not be a better place to live in. Since racially offensive terms increase racial prejudice, they make society a worse place. It logically follows that the Washington Redskins name is unethical because it is racially offensive to Native Americans.

Deontological reasoning would not support keeping the Washington Redskins name as is. Applying the universalization manoeuvre, we ask ourselves: What if every sports team had a racially offensive name that perpetuated racist behaviour throughout society? Would this be a pleasant world to live in? The answer to this question is clearly no. A society with more racial prejudice would not be a better place to live in. Since racially offensive terms increase racial prejudice, they make society a worse place. It logically follows that the Washington Redskins name is unethical because it is racially offensive to Native Americans.

The Washington Redskins team name would also be considered unethical when using a virtue based moral reasoning approach. In virtue based logic the aim is to act so as to maximize a particular virtue. The virtue could be honesty, accountability, integrity, inclusiveness, fairness or any other virtue. Actions are right if they increase a particular virtue and wrong if they decrease a particular virtue. When assessed against almost any virtue, the use of the term Redskin is unethical. For example, it flies in the face of inclusiveness because it perpetuates the stereotype that Native Americans are inferior to other races. Likewise, it does not encourage accountability for the discrimination which has affected Native Americans since colonization. Since the use of the term does not increase virtues, applying virtue based reasoning would suggest it is unethical.

The Washington Redskins team name would also be considered unethical when using a virtue based moral reasoning approach. In virtue based logic the aim is to act so as to maximize a particular virtue. The virtue could be honesty, accountability, integrity, inclusiveness, fairness or any other virtue. Actions are right if they increase a particular virtue and wrong if they decrease a particular virtue. When assessed against almost any virtue, the use of the term Redskin is unethical. For example, it flies in the face of inclusiveness because it perpetuates the stereotype that Native Americans are inferior to other races. Likewise, it does not encourage accountability for the discrimination which has affected Native Americans since colonization. Since the use of the term does not increase virtues, applying virtue based reasoning would suggest it is unethical.

The ethical framework which provides the strongest argument that the Washington Redskins name is unethical is Rawlsian Liberalism. John Rawls used the example of politicians to illustrate how his philosophy works. Politicians make decisions on the rules and resource distribution of society. This benefits some people and harms others. Politicians naturally also care about their quality of life once they are out of power. They thus tend to make laws which favour the group they expect to be in upon leaving office. The key test then becomes if a politician would take the same action if they did not know what part of society they would be in upon leaving office. Actions which would be taken in these circumstances are considered right by Rawlsian liberalism.

The ethical framework which provides the strongest argument that the Washington Redskins name is unethical is Rawlsian Liberalism. John Rawls used the example of politicians to illustrate how his philosophy works. Politicians make decisions on the rules and resource distribution of society. This benefits some people and harms others. Politicians naturally also care about their quality of life once they are out of power. They thus tend to make laws which favour the group they expect to be in upon leaving office. The key test then becomes if a politician would take the same action if they did not know what part of society they would be in upon leaving office. Actions which would be taken in these circumstances are considered right by Rawlsian liberalism.

Applying Rawlsian liberalism to the Washington Redskins name is straightforward. Imagine you were the owner of a sports team and could name it anything you wished, but you did not know your own race, gender, age or other characteristics. In this scenario, would you risk giving the team a name that could be construed as a racial slur? There is a real possibility that you might end up part of the group being insulted by the slur. This is unpleasant, so you would be better advised to choose a non-offensive name. The Rawlsian framework would thus consider having a racially offensive name like Redskins to be unethical. If you would not take an action if you could be negatively affected by it in the Rawlsian hypothetical, then the action is unethical.

Applying Rawlsian liberalism to the Washington Redskins name is straightforward. Imagine you were the owner of a sports team and could name it anything you wished, but you did not know your own race, gender, age or other characteristics. In this scenario, would you risk giving the team a name that could be construed as a racial slur? There is a real possibility that you might end up part of the group being insulted by the slur. This is unpleasant, so you would be better advised to choose a non-offensive name. The Rawlsian framework would thus consider having a racially offensive name like Redskins to be unethical. If you would not take an action if you could be negatively affected by it in the Rawlsian hypothetical, then the action is unethical.

Other Cases

It is useful to look at the use of the term Redskins in a broader context because societal norms constantly evolve. Washington is not the only sports team to use a Native American themed name and Native imagery. Teams at the professional and intercollegiate level have nicknames such as Redskins, Indians, Braves, Chiefs, Warriors, and many tribal specific names. These teams are under the same pressure to be respectful of Native Americans as Washington. Their actions thus become useful comparisons when assessing current social trends and future options for the Redskins. The many different actions of these teams shows that there are alternatives to the status quo which the Redskins should carefully consider.

It is useful to look at the use of the term Redskins in a broader context because societal norms constantly evolve. Washington is not the only sports team to use a Native American themed name and Native imagery. Teams at the professional and intercollegiate level have nicknames such as Redskins, Indians, Braves, Chiefs, Warriors, and many tribal specific names. These teams are under the same pressure to be respectful of Native Americans as Washington. Their actions thus become useful comparisons when assessing current social trends and future options for the Redskins. The many different actions of these teams shows that there are alternatives to the status quo which the Redskins should carefully consider.

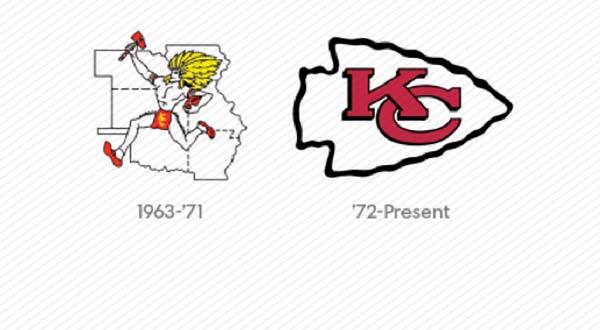

The most significant course of action teams have taken in response to pressure to be more respectful of Native Americans is a complete rebranding. For example, before 1972 Stanford University sports teams were known as the Indians and were represented by a cartoon logo which was widely viewed by Native American groups as offensive and unethical. The school responded to this criticism by completely removing all Native American imagery and changing its nickname to Cardinal. Likewise, Miami University underwent a comprehensive assessment of its sports teams’ use of Native American imagery. The review resulted in Miami’s nickname being changed from Redskins to RedHawks and all Native American imagery being discarded beginning with the 1997-98 season.20 The administrators at Miami and Stanford concluded that using Native American imagery as the basis for sports teams was unethical and needed to be changed.

Another option sports teams have is to get the approval of Native American groups. Consensual use of Native American imagery is ethically preferable because it ensures that the consequences for Native American groups are being considered by making them active agents in the decision making process. Not only does this maximize virtues such as inclusiveness, openness and fairness, but it also ensures that the use of Native American imagery is not offensive. No tribe would consent to the use of Native imagery which it considered harmful. For example, Florida State University has a very close relationship with the Seminole tribe. Following consultations with the tribe, the university made several changes to its sports traditions. Florida State redesigned the costume of its Chief Osceola mascot to better align with traditional Seminole dress and adopted a new logo with tribal approval.21 The fact that these changes were made with tribal input makes it easier for the university to argue it made the ethical choice.

Another option sports teams have is to get the approval of Native American groups. Consensual use of Native American imagery is ethically preferable because it ensures that the consequences for Native American groups are being considered by making them active agents in the decision making process. Not only does this maximize virtues such as inclusiveness, openness and fairness, but it also ensures that the use of Native American imagery is not offensive. No tribe would consent to the use of Native imagery which it considered harmful. For example, Florida State University has a very close relationship with the Seminole tribe. Following consultations with the tribe, the university made several changes to its sports traditions. Florida State redesigned the costume of its Chief Osceola mascot to better align with traditional Seminole dress and adopted a new logo with tribal approval.21 The fact that these changes were made with tribal input makes it easier for the university to argue it made the ethical choice.

There are also many sports teams which have made changes to their branding to be more respectful of Native Americans. For example, the Cleveland Indians gradually phased out their “Chief Wahoo” logo and replaced it with one that did not contain Native imagery. Likewise, the Chicago Blackhawks, Atlanta Braves, and Illinois Fighting Illini moved towards new mascots which did not involve dressing up as stereotypical Native Americans.23 The business decisions to make changes to team branding for these teams and many others were the results of ethical considerations and economics. From an ethical perspective, using logos and mascots which were offensive to Native Americans was the wrong thing to do. From an economics perspective, the controversy surrounding the use of Native American imagery posed a long term threat to brand value. By gradually transitioning away from the use of Native American imagery teams could maintain strong brand loyalty while limiting their exposure to reputational risk.

There are also many sports teams which have made changes to their branding to be more respectful of Native Americans. For example, the Cleveland Indians gradually phased out their “Chief Wahoo” logo and replaced it with one that did not contain Native imagery. Likewise, the Chicago Blackhawks, Atlanta Braves, and Illinois Fighting Illini moved towards new mascots which did not involve dressing up as stereotypical Native Americans.23 The business decisions to make changes to team branding for these teams and many others were the results of ethical considerations and economics. From an ethical perspective, using logos and mascots which were offensive to Native Americans was the wrong thing to do. From an economics perspective, the controversy surrounding the use of Native American imagery posed a long term threat to brand value. By gradually transitioning away from the use of Native American imagery teams could maintain strong brand loyalty while limiting their exposure to reputational risk.

The various actions taken by other sports teams to be more respectful of Native Americans make the actions of Redskins owner Daniel Snyder even more perplexing. Snyder appears determined to keep the status quo, and is on the record that the Washington Redskins will “NEVER” change their name. This position goes against the broader trend of sports teams moving away from Native American imagery. Moreover, the controversy that has erupted since Snyder declared his hardline stance has been damaging to Washington’s brand value. For example, merchandise revenue for the Washington Redskins has declined 43.8% since 2014.25 This suggests individuals are now more reluctant to be associated with the term Redskin and are less likely to purchase team-branded clothing. The negative impact this has on the bottom line suggests the status quo might not be the most profitable course of action going forward.

The various actions taken by other sports teams to be more respectful of Native Americans make the actions of Redskins owner Daniel Snyder even more perplexing. Snyder appears determined to keep the status quo, and is on the record that the Washington Redskins will “NEVER” change their name. This position goes against the broader trend of sports teams moving away from Native American imagery. Moreover, the controversy that has erupted since Snyder declared his hardline stance has been damaging to Washington’s brand value. For example, merchandise revenue for the Washington Redskins has declined 43.8% since 2014.25 This suggests individuals are now more reluctant to be associated with the term Redskin and are less likely to purchase team-branded clothing. The negative impact this has on the bottom line suggests the status quo might not be the most profitable course of action going forward.

Declining revenue is the first indicator the Redskins name fails the Tucker five question framework for ethical decision making. This model asks whether a decision is profitable, legal, sustainable, fair and right.26 While the name is currently legal, the Redskins’ trademark is under threat, so it may not be legal in future. The actions of other teams indicate that an offensive name is unsustainable and the harm to Native Americans suggests it is unfair. This leads to the inevitable conclusion that keeping the name is not right.

Decision

The Washington Redskins’ use of a racial slur as their team name is unethical. While a narrow understanding of the ethical framework of contractarianism suggests it would be ethical to keep the name, the ethical frameworks of utilitarianism, consequentialism, and end-statism are inconclusive. In contrast, the ethical frameworks of deontological reasoning, virtue based reasoning and Rawlsian liberalism strongly suggest that use of the name Redskin is unethical and needs to stop. This position is strengthened by the actions of other sports teams, many of which have completely abandoned their use of Native American imagery or moved away from practices which Native American groups found to be offensive. The Redskins should consider these factors and carefully begin planning a move away from their use of a racial slur for Native Americans. Not only would this be the right thing to do, but it may also be more profitable as well. Other businesses should carefully consider the challenges the Redskins are currently facing when making ethical decisions about how to brand themselves in future.

RECENT UPDATE 2016: Who finds this name offensive? A diverse group does. Some revel in white guilt and others cringe at the term Redskin as a term that perpetuates prejudice and even others just don’t want ‘systematically disadvantaged people’ to be offended or don’t know much about Indigenous history and figure it is better that a football team not objectify a cultural group, a safe bet. All legitimate opinions in their own way.

Are there multiple interpretations of what this team name represents? Evidently. However, Redskins is on the whole an othering terminology, that doesn’t celebrate the spirit of Indigenous people so much as tokenize a proud people(s).

Of course, in 2016, if you ask indigenous people in a poll you might find that 9 out of 10 Native Americans polled have a different answer. This is an emotional charged issue. We should remain skeptical of polling data, but we should also engage in testing ideas by actually polling the most relevant population.

UPDATE 2019: On the other hand, some of the polling on the other side seems a bit push poll-esq too. Maybe both are push polling, if you look below at the order of logos from Angus Reid Polling implying a clear hierarchy of ‘dominant’ groups and ‘colonized groups’, now which do you find is being celebrated with the corresponding logo or is been tokenized or is offensive?

We should be asking indigenous people, leadership and community at large, about this with more depth but it is possible the results will show it is not universally offensive…hence the democratic process of who wields power makes the final call…answers are complicated. Decisions will upset…

UPDATE 2020: Note that in July 2020, the Washington Redskins have removed Redskin from their name, post the George Floyd tragedy. So a public uproar over another offensive tragedy relating to race can sharpen and simplify a shift of opinion quickly. The Edmonton Eskimos will also change their name as of July 2020 . Change will be costly in the short run but long run sometimes symbolism matters.

References

1 Consoli, J. (2010, October 6). NFL Games Breaking Audience Ratings Records. Adweek. Retrieved October 3, 2016, from http://www.adweek.com/news/television/nfl-games-breaking-audience-ratings-records-116272

2 Vrentas, J. (2014, April 3). The Battle of Washington. Sports Illustrated. Retrieved October 3, 2016, from http://mmqb.si.com/2014/04/03/washington-nfl-team-name-debate

3 Brady, E. (2013, May 10). Daniel Snyder says Redskins will never change name. USA Today. Retrieved October 3, 2016, from http://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/nfl/redskins/2013/05/09/washington-redskins-daniel-snyder/2148127/

4 Blackhorse v. Pro Football, Inc. Decision. (2014, June 18). United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved October 3, 2016, from https://www.uspto.gov/about-us/news-updates/blackhorse-v-pro-football-inc-decision

5 NON-DISPARAGEMENT OF NATIVE AMERICAN PERSONS OR PEOPLES IN TRADEMARK REGISTRATION ACT. (2013). 113th Congress. Retrieved October 3, 2016, from https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/granule/CRI-2013/CRI-2013-NON-DISPARAGEMENT-OF-NATIVE-AMERIC-89BA9D/content-detail.html

6 Obama weighs in on ‘Redskins’ (2013, October 5). ESPN. Retrieved October 3, 2016, from http://www.espn.com/nfl/story/_/id/9772653/president-obama-washington-redskins-legitimate-concerns

7 Washington Redskins Original Americans Foundation. (2014, March 24). Retrieved October 3, 2016, from http://www.washingtonredskinsoriginalamericansfoundation.org/

8 South Dakota tribe returning donation from Redskins. (2015, August 7). ESPN. Retrieved October 3, 2016, from http://www.espn.com/nfl/story/_/id/13395107/south-dakota-tribe-returning-25000-donation-washington-redskins

9 Moldoveanu, M. (2014, August). Managerial Models and Methods for Moral Reasoning. Foundation for Business Ethics.

10 Vrentas, J. (2014, April 3). The Battle of Washington. Sports Illustrated. Retrieved October 3, 2016, from http://mmqb.si.com/2014/04/03/washington-nfl-team-name-debate

11 Moldoveanu, M. (2014, August). Managerial Models and Methods for Moral Reasoning. Foundation for Business Ethics.

12 Moldoveanu, M. (2014, August). Managerial Models and Methods for Moral Reasoning. Foundation for Business Ethics.

13 Freed, B. (2016, February 5). Poll: 25 Percent of Football Fans Think Redskins Should Change Their Name. Washingtonian. Retrieved October 3, 2016, from https://www.washingtonian.com/2016/02/05/poll-25-percent-of-football-fans-think-redskins-should-change-their-name/

14 Moldoveanu, M. (2014, August). Managerial Models and Methods for Moral Reasoning. Foundation for Business Ethics.

15 Moldoveanu, M. (2014, August). Managerial Models and Methods for Moral Reasoning. Foundation for Business Ethics.

16 Moldoveanu, M. (2014, August). Managerial Models and Methods for Moral Reasoning. Foundation for Business Ethics.

17 Moldoveanu, M. (2014, August). Managerial Models and Methods for Moral Reasoning. Foundation for Business Ethics.

18 Moldoveanu, M. (2014, August). Managerial Models and Methods for Moral Reasoning. Foundation for Business Ethics.

19 What is the history of Stanford’s mascot and nickname? Stanford University. Retrieved October 3, 2016, from http://www.gostanford.com/sports/2013/4/17/208445366.aspx

20 Ellison, C. W. (Ed.). (2009). Mascot Story. Miami University. Retrieved October 3, 2016, from http://miamioh.edu/about-miami/diversity/miami-tribe-relations/mascot-story/

21 Culpepper, C. (2014, December 29). Florida State’s unusual bond with Seminole Tribe puts mascot debate in a different light. The Washington Post. Retrieved October 3, 2014, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/colleges/florida-states-unusual-bond-with-seminole-tribe-puts-mascot-debate-in-a-different-light/2014/12/29/5386841a-8eea-11e4-ba53-a477d66580ed_story.html

22 Brown, D. (2014, January 9). Cleveland Indians demote Chief Wahoo logo. Yahoo Sports. Retrieved October 3, 2016, from http://sports.yahoo.com/blogs/mlb-big-league-stew/cleveland-indians-marginalize-chief-wahoo-logo-081024357–mlb.html

23 Ryan, S. (2016, May 3). Illinois to select new mascot. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 3, 2016, from http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/college/ct-university-of-illinois-mascot-chief-illiniwek-20160502-story.html

24 Brady, E. (2013, May 10). Daniel Snyder says Redskins will never change name. USA Today. Retrieved October 3, 2016, from http://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/nfl/redskins/2013/05/09/washington-redskins-daniel-snyder/2148127/

25 Rovell, D. (2014, September 5). Redskins merchandising dips sharply. ESPN. Retrieved October 3, 2016, from http://www.espn.com/nfl/story/_/id/11471322/washington-redskins-merchandising-sales-drop-438-percent-year-research-shows

26 Powers, R. (2016, September 15). Business Ethics. Lecture presented in University of Toronto Rotman School of Management, Toronto.