Federal Vote Choice in Quebec

It’s Sovereignty, Stupid!

by M.Arnot, M.Campbell, E.Hjertaas, D.Moore & B.Nolan

Introduction

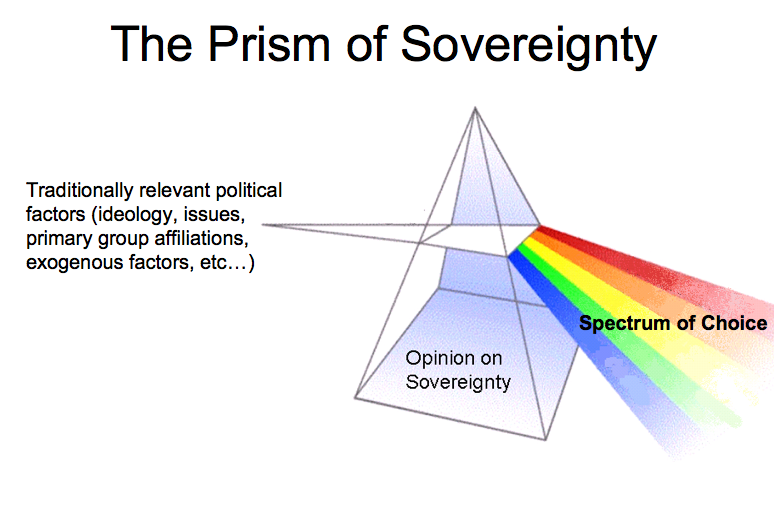

What determines vote choice in federal elections in Quebec? What structural factors define the nature of this choice, and what agential factors influence how it is made in the election itself? Any answer to such questions depends on an understanding of the attitudinal prism that shapes voter perceptions: the divisive issue of sovereignty.

Quebec’s nationalist movement is one of the strongest in the developed world, dominating the province’s politics (Meadwell, 1993: 203). Within it there is a dichotomy between the sovereignist bloc favouring independence from Canada, and the federalist block which combines those who support the development of a decentralized federalism, and those who support the status quo (Blais & Nadeau, 1992: 91). The emergence of the Bloc Québécois (BQ) since 1993 “virtually guarantees that Quebecers’ positions on the sovereignty question will strongly affect both their political perceptions and their federal vote” (Blais, et al., 2002: 104). In federal politics, the BQ is the party of the sovereignists, while the federal Liberal Party has traditionally been associated with the federalists (though it has competed for this position with the Conservative Party). Support for sovereignty made a Quebecer 34% more likely to vote for the BQ, and 23% less likely to vote for the Liberals, in the 2000 election (Blais, et al., 2002: 224). For voters in the province, “the Bloc Quebecois is the logical shelter of those Quebecers who support Quebec sovereignty,” and the party’s success “hinges on the flux in the sovereignist movement” (201-202). The Liberal gains in 2000 in Quebec were a partial result of falling support for sovereignty (201). The prism of support for sovereignty – which plays a mediating role comparable to a degree to the phenomenon of party identification as it is described by the Michigan school (Campbell, et al., 1985: 30) – is thus critical in defining election outcomes in Quebec.

We will examine the different ways in which this attitudinal prism applies to different segments of voters in the province, arguing that support for sovereignty is determined by national identity, feelings of unequal respect and treatment, and perceptions of the economic consequences of separation. As evidence for these determinants, we will apply them to explain the socio-demographic cleavages existing in preferences regarding the sovereignty question in Quebec. We will then consider how the most significant political actors – party leaders, parties themselves, and the media – interact with sovereignty preference, employing their political capital to shape it into popular vote choice according with their distinct interests. We conclude that federal election outcomes are a function of these agents’ success at manipulating the perceptions of the three determinants of that critical voting block whose vote choice is variable.

There are two predominant theoretical models that have been developed to explain voter support for Quebec independence. First, the rational choice approach uses multivariate analysis to examine the rational decision-making calculus of individuals (Mendelsohn 2003: 512). Building on earlier findings that the perceived impact of sovereignty on future quality of life was a major factor in individual decision-making (Blais & Nadeau 1992: 96), this model has posited that “Quebecers base their choice in large part on an evaluation of the likely costs and benefits of sovereignty in two major areas: the economy and the situation of the French language in Quebec” (Nadeau, Martin, & Blais 1999:526). Personal dispositions, created by one’s level of Quebec national identity, influence this process (533).[1] According to this theory, French speakers perform cost-benefit calculations based on their perceptions of both the current level of threat to the French language, and prospective changes to this threat level in the event of sovereignty (Mendelsohn 2003:515).

Second, the socio-psychological approach seeks to explain the motivation behind social movements through opinion polls that track Quebecers’ “resentment, feelings of status denial, ethnic grievances and self-confidence, along with [perceptions of the] costs and benefits of sovereignty and federalism” (Mendelsohn 2003:512)). It focuses on grievances, collective incentives, and expectancies of success as the principal motivators of the sovereignty movement (Pinard & Hamilton 1986: 229): a rise in the levels of felt deprivations, and/or an increased belief in the positive consequences of sovereignty, will lead to a higher level of support for the separatist cause (Mendelsohn 2003: 512).

The two models are related. Both portray rational decisions based on the prospective consequences of sovereignty to language and the economy as crucial variables in determining choice. The socio-psychological approach places great emphasis on ethnic grievances as the major internal motivation, while the rational choice model focuses on national attachment. These two concepts are related in that felt deprivations are probably a major factor in determining one’s attachment to Canada. The greatest distinction has been in methodology. Pinard’s multi-decade study of opinion polls with varying formats has created an explanation of motivation that is “dense, contextual, and highly political” (Mendelsohn, 2003:514). The rational choice approach, through its strict use of statistical techniques to isolate variables, has given a much narrower but probably more accurate picture of the extent to which the factors identified influence decision making.

Matthew Mendelsohn in 2003 sought to test, correct, and combine previous findings. The study subjects the rational choice approach’s accepted variables to falsification tests, the necessity of which is methodically explained (516-518). He criticizes the socio-psychological approach for its use of inconsistent methods and definitions of variables, and for the large number of variables mentioned, which causes difficulties when attempting to measure their relative effect.

Mendelsohn’s comparative study uses a larger sample size than previous efforts, allowing for more reliable data. He finds that a rational calculation based on medium-term economic consequences is indeed the major factor in decision-making, with an impact more than two times that of the nearest variable, which was the perception that Quebecers are not recognized as equals. This grievance had been discussed within the socio-psychological approach. These two variables were the decisive elements in individual decision-making (525). Mendelsohn finally concluded that national identity was another important, independent variable in sovereignty support (528).[2] Describing national identity as a concept similar to party identification, Richard Nadeau and André Blais wrote in 1992 that it “involves … feelings toward a group (in this case a territorially-based collectivity), which tend to be stable and imply a general propensity to react in certain ways on issues of Quebec/Canada relations” (95).

Adding nuance, Paul Howe has made an interesting finding that for Francophones, the influence of cost-benefit calculations was dependent on national identity. In individuals with a strong sense of Quebec nationalism, these calculations barely matter, while they are more important to choice in those with weaker Quebec identities (Howe 1998: 32).[3] What must be noted from this is that the other two variables will only be relevant for those who do not belong to this strongly nationalist block.

Turning now to the three significant factors: national identity (defined at least in this instance by the varying level of attachment to Canada), the perceptions of unequal respect and recognition, and rationally calculated economic considerations. In this paper they will be referred to as the structural determinants of voter preference on the issue of sovereignty. They are the broader phenomena that provide the foundation for a personally relevant choice for individuals in Quebec, in this case on the issue of sovereignty. For the sake of analytical depth the following paragraphs will explore their relation to one another and the underlying reasons for their salience.

National identity and perceptions of unequal respect and recognition are closely related as social-psychological factors, and together motivate sovereignist support within Quebec’s French speaking majority. Grievances or aspirations perceived to be shared across a collectivity can motivate people to participate in social movements (Pinard & Hamilton, 1986: 227) by prompting the formation of group identity. Identity evolves in stages: it first combines with political empowerment stemming from some expectancy of success (231), fostering moral obligations rooted in norms, values, and ideologies; and in turn motivates selfless contribution to the collectivity’s defining interests (230). These societal forces must be very powerful because, in changing people’s values and creating new political allegiances they are combating the stabilizing socializing influence that parents have on their children (Stacey, 1966: 138).

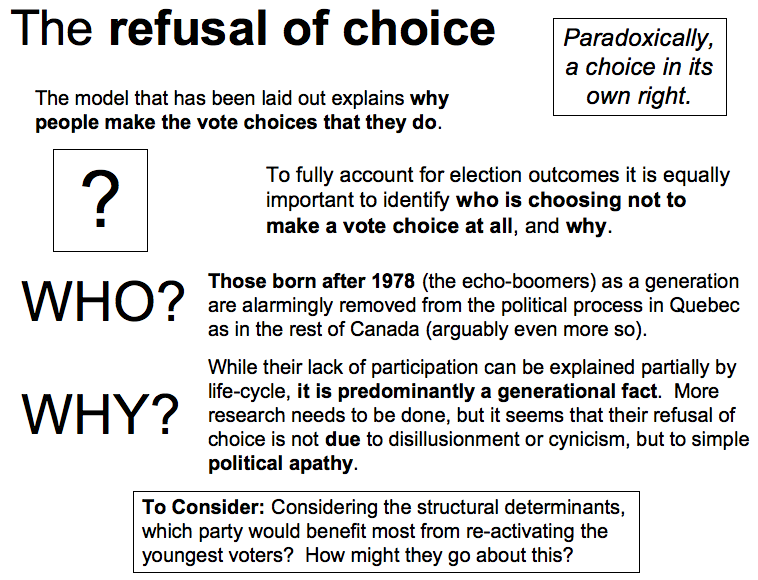

In Quebec, collective identity emerged from the Quiet Revolution in the 1960s coinciding with the socialization of the baby boom generation (Martin & Nadeau, 2002: 146). This revolution was a rapid post-war modernization of state and society which corresponded with a mass rejection of traditional “French-Canadian” values (147). Enforced by the Roman Catholic Church (Meadwell, 1993: 205), these values were conservative, rural, religious, and wary of government (Martin & Nadeau, 2002:147). Huge economic disparities existed between the French population and the English, prompting powerful linguistically rooted grievances. The post-war economic boom facilitated the mobilization of one of the earliest engines in the emerging sovereignist collective identity: the young, French urban labour force (148). This group was activated by recognition of common grievance and a feeling of political strength in numbers. As the identity coalesced, post-materialist reasons for the movement emerged (148), along with feelings of moral responsibility to the group, which came to be labeled “Québécois” as opposed to “French-Canadian” (Ibid.). This new group adopted progressive, urban, secular, and interventionist values (147) diametrically opposed to their forebears.

In Quebec, collective identity emerged from the Quiet Revolution in the 1960s coinciding with the socialization of the baby boom generation (Martin & Nadeau, 2002: 146). This revolution was a rapid post-war modernization of state and society which corresponded with a mass rejection of traditional “French-Canadian” values (147). Enforced by the Roman Catholic Church (Meadwell, 1993: 205), these values were conservative, rural, religious, and wary of government (Martin & Nadeau, 2002:147). Huge economic disparities existed between the French population and the English, prompting powerful linguistically rooted grievances. The post-war economic boom facilitated the mobilization of one of the earliest engines in the emerging sovereignist collective identity: the young, French urban labour force (148). This group was activated by recognition of common grievance and a feeling of political strength in numbers. As the identity coalesced, post-materialist reasons for the movement emerged (148), along with feelings of moral responsibility to the group, which came to be labeled “Québécois” as opposed to “French-Canadian” (Ibid.). This new group adopted progressive, urban, secular, and interventionist values (147) diametrically opposed to their forebears.

The new collective identity was a powerful force in the socialization of the emerging generation, widely overcoming the countervailing force of previous generations’ more nebulous “French-Canadian” label. The evidence for this is that in 1970, when the pre-boom generation was the majority of the electorate, only 21% of that electorate identified itself as primarily “Québécois.” By 1997 that number had grown to 63% (146), a change that statistical analysis reveals to be almost entirely attributable to the eclipsing of the pre-boomers by the younger generations that had been socialized into this identity (Ibid.). A central grievance shared by members of this group is that of unequal recognition by the rest of Canada, which includes perceptions of unfair treatment by the federal government and a feeling that “Anglophones do not care about French-speaking Quebeckers” (Mendelsohn 2003: 527).

The third determinant cited, based in rational choice models, is a counterweight to the social-psychological based determinants in that it has traditionally served as a significant detractor from sovereignist support. It is drawn from rational calculations of the medium-term consequences of sovereignty on which there is considerable disagreement even among experts. In 1999 a survey showed that 49% of Quebecers predicted a worsened economic situation in a sovereign Quebec, compared to only 29% who predicted improvement (Nadeau & Blais: 1999; 529). Prospective voting, based on what voters suspect the economic situation will be five years from the present, applies in this case. If Quebecers can be convinced that sovereignty will improve future economic expectancies, they will be more likely to support the Bloc Quebecois (Mendelsohn 2003: 512). If their perceptions are negative, then they are more likely to support one of the federalist parties.

There are two different ways in which individuals can be affected by economic considerations. Egocentric considerations refer to those factors which affect the economic prospect of the individual him or herself. Relevant egocentric indicators include how the incumbent party’s perceived influence on personal disposable income or individual employment rate affects an individual’s voting behavior. Sociotropic considerations refer to those factors which affect the economic health of an individual’s broader societal context. Relevant sociotropic indicators describe the incumbent party’s perceived influence on the conditions in the country as a whole affects voting behaviour: perceptions of changes in the real disposable income per capita, or the national unemployment rate (Nadeau & Blais 2000:79). In Quebec, egocentric factors in particular have a significant effect on sovereignty support (Howe, 1998: 39).

The economic uncertainty of sovereignty lends a degree of risk acceptance to voting for the Bloc Quebecois (Martin & Nadeau, 2002: 151). Risk-averse voters tend to be less supportive of the sovereignist option “because they put more weight on the worst-outcome components of the decision” (Mendelsohn 2003: 535). When outcomes are uncertain, prospect theory states that people will do more to avoid loss than they will to seek gain (Martin, 1994: 347). Considering the relative stability of the Quebec economy over the past thirty years, and the belief that such stability will continue indefinitely, this suggests that many voters would find the risks of sovereignty too great and favour the status quo.

Cleavages

Persuasive evidence for the impact of these three structural determinants can be found in the nature of Quebec’s cleavages in voting. After these cleavages are introduced, the structural determinants will be employed to account for them, testing their explanatory power.

The most dramatic division in sovereignty support is language. When examining voting behaviour in Quebec, this cleavage is strikingly large. In the 2000 federal election, non-Francophones were 42 percentage points more likely than French speakers to cast their vote for a Liberal, while French speaking voters were an estimated 35.6 percentage points more likely to support the Bloc Quebecois (Blais et al. 2002: 95, 223).. Study of the language cleavage has been hampered by the difficulty of attaining large enough samples for Anglophones and especially Allophones, but some trends can be seen from the limited data available. A 2005 poll found that 62% of Francophones would vote for sovereignty, while 87% of Anglophones would vote against it. Interestingly, 31% of Allophones are in favour of sovereignty (Léger Marketing: 4); this general trend is quite consistent over time.

Some researchers have stated that “the sense of cultural insecurity inherent in Quebec’s status as a small French-speaking island in an ocean of English leads many Francophones to consider sovereignty as a form of linguistic assurance” (Martin & Nadeau 2002: 151). In fact, “among the most often voiced grievances [expressed by Francophones] are first those concerning their cultural life: first and foremost, worries with regard to their language, culture, and institutions” (Pinard & Hamilton 1986:235). Unequal recognition of Francophones in Canada and the attitudes of superiority among English speakers have also been recognized as major grievances held by French speakers (Pinard & Hamilton 1986: 236-241).

Although there is not a proven causal link between opinion on sovereignty and fears for the future of the French language, there is a strong correlation. A significant number of Francophones believe that sovereignty would bring linguistic benefits; in a 1999 poll, 56% anticipated that the situation of French would improve in Quebec after separation, but only 9% thought it would worsen (Nadeau et al. 1999: 529). Of those who believe that the situation of the French language and culture would improve with sovereignty, 74% would vote in favour, while 86% of those who believe it would worsen would be opposed (Martin & Nadeau 2002: 251). It is known that the overwhelming majority of non-Francophones foresee negative consequences to independence, including linguistic ones (Nadeau et al. 1999: 529), and 47% indicated in 2005 that they would consider leaving the province if it became an independent country (Léger Marketing: 17) An overwhelming majority of Anglophone Quebecers, 80%, foresee adverse ramifications for the English community in the province. Strikingly, 70% believe the disappearance of their community to be somewhat or very likely after secession (529). They are also in near-unanimous opposition to calls for sovereignty. In the 1995 referendum, only 5.6% of non-Francophones voted in favour, while 57.8% of the Francophone community supported sovereignty (Martin & Nadeau 2002:145). The reason for this correlation without causation will be discussed in the next section.

Apart from language, age is the most critical socio-demographic factor in defining feelings towards sovereignty. In fact, since the early 1980s language and age have been the only statistically strong and persistent cleavages on the question of sovereignty, far stronger than social or economic identity factors such as gender, social class, sector of employment, or educational level achieved (Martin, 1994: 347). The slight gender cleavage can be largely explained away as a product of the life-cycle fact that women compose a larger proportion of the oldest generation (due to the greater longevity of women) which is the one least likely to be sovereignist (Martin & Nadeau, 2002: 144), the reasons for which will be explored in the paper.

Apart from language, age is the most critical socio-demographic factor in defining feelings towards sovereignty. In fact, since the early 1980s language and age have been the only statistically strong and persistent cleavages on the question of sovereignty, far stronger than social or economic identity factors such as gender, social class, sector of employment, or educational level achieved (Martin, 1994: 347). The slight gender cleavage can be largely explained away as a product of the life-cycle fact that women compose a larger proportion of the oldest generation (due to the greater longevity of women) which is the one least likely to be sovereignist (Martin & Nadeau, 2002: 144), the reasons for which will be explored in the paper.

In considering the dynamics that emerge from the demographic landscape of age, it is critical to understand the difference between generation and life-cycle. Generation-based explanations turn on the concept of political socialization, which is the acquisition, at a young age, of political identities that persist through adulthood (Blais & Nadeau, 1992:146). Environmental factors specific to a certain era can affect the political socialization of entire generations of young people. Thus, a generational explanation of the age cleavage highlights factors unique to a generation that will remain relevant in influencing its opinions as it ages. Life-cycle explanations, on the other hand, focus on the issues associated with being in certain stages in life, and thus should be constant in their influence on certain age-groups regardless of generation. An important consequence that follows logically from this distinction is that a generational explanation, unlike a life-cycle explanation, has inevitable bearings on social change over time (Putnam, 2000: 248).

Whether or not life-cycle factors can cause major societal change depends entirely on the stability of the demographic makeup of the province. Quebec experienced a precipitous drop in fertility rates – beginning in the mid 1950s and stabilizing somewhat in the 1970s (although with the end of the echo boom it has begun to drop again since the early 90s (Institut de la statistique Québec, 2001)) – constituting the most remarkable demographic development in Quebec in the 20th century (Caldwell & Fournier, 1987: 31). From 1954 to 1967 alone, the birthrate dropped from over 4.0 to under 1.5 (Ibid.). This has resulted in Quebec undergoing one of the most dramatic aging processes in the industrialized world (32). Considering this, there is no reason to believe that life-cycle factors will be stable, and thus they can be expected to drive societal change in their own right. Furthermore, these demographic facts are important to generational factors as they will serve to either amplify or mitigate the influence of given cohorts. Ultimately, it is important to consider demographics in order to understand the constitution of the electorate, especially now as the pre-’54 generation (who are now over 50) move out of the majority, and as their children (the echo-boom) enter political society.

The third critical factor is region. Essentially, a region is an area where a significant degree of homogeneity on a given factor can be expected in the population because of the interplay of various shared characteristics. To facilitate studies of voting behaviour, region can be classified as the geographic area encompassed in the boundaries of an electoral riding, or groups of electoral ridings, though this classification will inevitably be flawed. Sub-provincial regions are usually characterized as groups of ridings focused on sections of cities, suburbs, or areas with particular characteristics, like closeness to a border, or similar rural settlement patterns. The geographic location of a constituency determines distance from population centers; if a constituency is distant from a main center, a feeling of isolation or marginalization often surfaces. The distribution of natural resources affects the kind of economic activities that exist within the region. Urban or rural character is also important, because rural ridings have less population and slower economic growth than cities, and thus tend to be more conservative (Carty and Eagles, 2005: 8). Socio-economic factors can be included in a regional analysis. These factors are heavily influenced by settlement patterns, as well as political factors due to the historical legacy of previous elections and political activities (9).

The third critical factor is region. Essentially, a region is an area where a significant degree of homogeneity on a given factor can be expected in the population because of the interplay of various shared characteristics. To facilitate studies of voting behaviour, region can be classified as the geographic area encompassed in the boundaries of an electoral riding, or groups of electoral ridings, though this classification will inevitably be flawed. Sub-provincial regions are usually characterized as groups of ridings focused on sections of cities, suburbs, or areas with particular characteristics, like closeness to a border, or similar rural settlement patterns. The geographic location of a constituency determines distance from population centers; if a constituency is distant from a main center, a feeling of isolation or marginalization often surfaces. The distribution of natural resources affects the kind of economic activities that exist within the region. Urban or rural character is also important, because rural ridings have less population and slower economic growth than cities, and thus tend to be more conservative (Carty and Eagles, 2005: 8). Socio-economic factors can be included in a regional analysis. These factors are heavily influenced by settlement patterns, as well as political factors due to the historical legacy of previous elections and political activities (9).

In terms of electoral support for each federal party, it is difficult to differentiate between regional and linguistic causality. In 1993, the strongest Liberal vote was confined to mostly Anglophone and Allophone ridings in Montreal, and strongly Anglophone ridings along the borders. The Bloc Québécois won 54 ridings, essentially, all of predominantly French-speaking Quebec (Drouilly, 1997: 47), which may be due in part to massive popularity of Lucien Bouchard as leader of the Bloc. The Conservative vote in 1993 collapsed across the country, so it is difficult to draw any conclusions. The one Conservative seat went to Jean Charest in Sherbrooke (a seat which later went Bloc), but this seems to be more as a result of the candidate than any regional effects. The NDP also fared terribly in Quebec that year, receiving only 1.5% of the vote, with its highest percentage (4.5%) in Outremont (48). In the 1993 election, Quebec seems to have been polarized between the Liberals and the Bloc. These results reflect a “race vote,” as Pierre Drouilly calls it: an almost unanimous rejection of the idea of Quebec sovereignty by non-Francophones (138) (the notable divide within this group between Anglophones ans Allophones was discussed above). This usually translates into support for the Liberals as the only major alternative to the Bloc, but the Conservative party occasionally receives a strong federalist vote in Quebec. However, the idea of a “race vote” does not completely discount the idea of region as an influential factor. Francophone support for sovereignty is far from unanimous, even in the most strongly Francophone and BQ ridings.

In the 1995 referendum on sovereignty, the Francophone “yes” vote remained steady at about 60% unless the district was less than half Francophone, in which case it fell below 50% (293 Table 9). In metropolitan Québec, 96.6% of residents are Francophones, the highest proportion in Quebec. If language were the only salient issue, metropolitan Quebec should also have voted “yes” in the highest proportion. This is not the case, with the overall “yes” vote at 55% and Francophone “yes” vote at 57%. This was the second lowest level of Francophone support in the province. The highest level of sovereignty support was in “la couronne de Montreal,” with 56.3% overall, and 65.2% among the 86.4% of its population that is Francophone. The district with the highest “yes” vote among Francophones is Montreal East, with 66.7%. Only 83% of its residents are Francophones and the overall “yes” vote was 55.4% (294 Table 10). Language variations alone can not justify the wide disparities in Francophone support for sovereignty by region.

In the 1995 referendum on sovereignty, the Francophone “yes” vote remained steady at about 60% unless the district was less than half Francophone, in which case it fell below 50% (293 Table 9). In metropolitan Québec, 96.6% of residents are Francophones, the highest proportion in Quebec. If language were the only salient issue, metropolitan Quebec should also have voted “yes” in the highest proportion. This is not the case, with the overall “yes” vote at 55% and Francophone “yes” vote at 57%. This was the second lowest level of Francophone support in the province. The highest level of sovereignty support was in “la couronne de Montreal,” with 56.3% overall, and 65.2% among the 86.4% of its population that is Francophone. The district with the highest “yes” vote among Francophones is Montreal East, with 66.7%. Only 83% of its residents are Francophones and the overall “yes” vote was 55.4% (294 Table 10). Language variations alone can not justify the wide disparities in Francophone support for sovereignty by region.

The contact hypothesis may help to explain these differences. It holds that “Francophones in mixed ridings may have adjusted to the stresses of living between two worlds already, and may have economic or social ties to the Canadian majority,” which changes the nature of national identity and moderates perception of threat. Following from this logic is that “those living in heavily Francophone areas, meanwhile, may feel besieged [by a separatist message] without the mitigating effect of cross-cultural contact” (Lublin and Voss, 2002: 92). As will be discussed below, this phenomenon most likely has an important impact on national identity.

There is no significant denominational religious cleavage in Quebec voting behaviour. On the national scale, Catholics are inclined to support the Liberal Party, while Protestants, at least historically, have tended to divide their vote more or less evenly between the Liberals and the Conservatives (Kanji & Archer, 2002: 168). This does not occur in Quebec because of the Quiet Revolution and the rise of Quebec nationalism, which served to diminish the salience of the Roman Catholic Church in Quebec politics. It is more probable that a religious cleavage exists based on religiosity, distinguishing religious voters from secular voters rather than voters of different denominations. Beyond simply that Quebec “is distinguished” by a relatively low degree of religiosity (Blais, et al., 2002: 104) there is limited available research, forestalling its incorporation into our discussion, although it should certainly be explored in the future.

There is a strong body of evidence linking political knowledge to education (Fournier, 2002: 349; Lambert et al: 356). Of all factors that contribute to differences in awareness, the most important is education (Gidengil et al., 2004: 50). Johnston et al. examined Quebecers regarding their support for the 1992 Charlottetown Accord. The group found that more educated voters were more likely to support the Accord, however “with the passage of time, differences … [in] levels of education … have decreased as determinants of sovereignty support” (Martin & Nadeau, 2002: 9). In the 1995 Referendum, 44% of voters with a university degree supported sovereignty, as opposed to groups with secondary and some post-secondary, 52% of whom supported sovereignty. Education is not a significant cleavage, though there is a clear pattern in sovereignty support. The median-educated Quebecer (secondary or some post-secondary) is slightly more likely to support sovereignty, however both lower and higher educated cohorts are 8-10 percentage points less likely to do so. Blais and Nadeau have found that rather than increasing support for sovereignty, “increased levels of formal education in Quebec society might contribute to high levels of interest” (25).

In the 1995 Referendum, 44% of voters with a university degree supported sovereignty, as opposed to groups with secondary and some post-secondary, 52% of whom supported sovereignty. Education is not a significant cleavage, though there is a clear pattern in sovereignty support. The median-educated Quebecer (secondary or some post-secondary) is slightly more likely to support sovereignty, however both lower and higher educated cohorts are 8-10 percentage points less likely to do so.

. There is a cleavage in sovereignty support based on ideology. Sovereignists tend to be more “left” than non-sovereignists, and the movement itself found its origins in leftist ideology, eventually developing post-materialist justifications (this was discussed earlier). Interestingly, the leftist composition of the movement is not based solely on the attraction it holds for those who share the same ideological leanings. In the 1993 election, sovereignty was so important that sovereignist voters aligned themselves ideologically with the leftist sovereignty movement. Their “positions on other issues came to cleave along one’s position on sovereignty” (Hinich et al., 1997). The ideological cleavage in the movement appears to be mainly related to its ability to realign voters to match its leftist origins.

Significant cleavages in opinion on the sovereignty issue based on social class have faded nearly completely (Martin, 1994: 347). During the industrialization of the post-war years the recognition of differences in material wealth and control over the means of production in Quebec between the English and the French populations shaped the proto- sovereignist movement (Martin & Nadeau, 2002: 148). Economic inequality diminished from the 60s to the 80s, and with it the importance of social-class as a “sovereignist” identity component faded to the extent that now there is no statistically significant cleavage at all.

Applying the Structural Determinants to Cleavages

There are thus three main cleavages – language, age, and region – which can be explained using different combinations of the three structural determinants of sovereignty support. The determinants’ explanatory power supports their validity.

Unequal respect and recognition

Recent studies have found that fears for the future of the French language are, in fact, not one of the major determinants of sovereignty support in Quebec. (Mendelsohn 2003: 525). When all other variables are held equal, an individual who perceives a threat to the French language and believes that sovereignty could improve this problem does not have a much higher level of support for independence (525). Mendelsohn’s explanation is that, in his study, only 33% of Francophones believed that sovereignty could improve their language’s situation, even though 56% of them thought it was threatened (528). This large decrease from the levels of only a decade ago, according to the author, shows that now “for most Quebecers the threat to French comes not from Canada but elsewhere” (528). An increased awareness of the results of globalization is a plausible recent change which seems to have decreased the impact of language concerns.

Instead, the linguistic differences in voting between Francophones, Anglophones, and Allophones occur because of the different feelings, identities, and interests that the groups possess. These differences are manifested in all three of the determinants of the sovereignty support, including the first, which is the Francophone perception of unequal respect and recognition from English Canadians. Low levels of Anglophone support for sovereignty are then partially explained by the mainly Francophone nature of this grievance (Pinard & Hamilton 1986:235). For Allophones, Bill 101’s imposition of the French language may have resulted in an increased sympathy for this concern among this population as well.

There is a large amount of statistical support for the existence and influence of this feeling of unequal treatment. In a 1980 survey, 54% of Francophones agreed with the statement that “English Canadians often tend to consider the French Canadians to be inferior to them” (238), and this has continued to be a prevalent opinion (Mendelsohn 2003: 527). Francophones with such feelings were found to be more than three times more likely to vote for sovereignty than against it in the 1980 referendum, while individuals with very low levels showed a pattern that was almost the exact opposite (Pinard & Hamilton 1986: 245). The findings pointed to the conclusion that the feelings of unequal respect and recognition are necessary for the Quebec independence movement and an important factor in recruitment (241). The perception of unequal respect and recognition is prevalent and influential in Quebec’s Francophone population, but not a factor for Anglophones. This is a partial explanation for the linguistic cleavage.

National identity

Language is also highly correlated with national identity, the second determinant.[1] Researchers have noted that in the post-war era the increasingly Quebec-oriented identity of Francophone Quebecers become rooted in language (Martin & Nadeau 2002: 146). Identity has a clear correlation with separatist beliefs: in a survey of approximately 900 Francophone Quebecers, it was found that individuals with an exclusive Quebec identity (and therefore little to no attachment to Canada) had a 93% chance of being sovereignist, while those who favoured Canada had only a 25% chance of supporting sovereignty (94). The authors concluded that “the great majority of Francophone Quebecers define themselves as Quebecers first and this pushes them toward the sovereignty option” (97). When 68% of Francophone Quebecers identify more with their province, and only 6% have a stronger attachment to Canada, identity will play a “crucial” role in determining support for independence (91, 95).

In 1995, only 7% of Anglophones primarily identified with Quebec (and therefore had a reduced level of attachment to Canada) resulting in weaker forces pulling them towards independence. The reason for this linguistic difference in identity is clear when one considers the linguistic basis of Quebec national identity that was mentioned above. Once again, the lukewarm Allophone support for sovereignty seems to originate in feelings which are in between the two other linguistic groups. In a population with many recent immigrants it is hardly surprising that they are more likely than English-speakers to be proud to be Canadian, but they are also more likely than Anglophones to be proud to be Quebecois (Léger Marketing, 2005 3). This is an admittedly crude indicator of national identity, but it does at least show that their national identity is probably more favourable towards sovereignty than that of Anglophones.

National identify also provides a powerful account for the age cleavage. Over 75% of those who identify primarily as Québécois voted “Yes” in the 1995 referendum, obviously a powerful indicator of sovereignist views (Martin & Nadeau, 2002: 145). As has been shown, such identification is localized in the boomer and younger generations, but to consider only this is to leave a major question unanswered. Many people, especially in the post-boom generation (Gen-X) do not support the sovereignty movement despite a Québécois identity. What explains that? Furthermore, statistical evidence suggests that identity only partially explains the apprehension of the oldest generations towards sovereignty, what other factors are relevant?

Finally, we can partially account for the regional cleavage through the determinant of national identity. The seventeen ridings where francophone support is lower than 50% are found in the West Island, Outaouais and Beauce. Montreal’s West Island has many Anglophones and allophones, supporting the idea that contact between linguistic groups mitigates perceived identity conflict. Since national identity is strengthened by such conflicts, contact between linguistic groups reduces support for sovereignty in such areas. Outaouais and Beauce are excellent examples of the ability of economic ties to alter national identity; in the case of these two regions decreasing sovereignty support. Economic considerations also serve as an independent determinant in voter decisions.

Rational calculations of the economic consequences of sovereignty

Rational calculations of the economic consequences of sovereignty

Differences in evaluations of the economic consequences of sovereignty between Francophones, Anglophones, and Allophones are the final element that accounts for the language cleavage. Since this has been found to be the most important factor in determining support for sovereignty among those with a weak Quebec national identity, even small differences in opinion can have a major impact. It has been found that although 49% of the population as a whole believes that the economic situation of a sovereign Quebec would worsen, this number is only 44% in the Francophone majority. That the non-Francophone minority could raise the average by 5 percentage points indicates a sizeable difference in opinion. Even more dramatically, while a near-unanimous 95% of Anglophones foresee an economic crisis after a vote for sovereignty, only 57% of Francophones share this opinion (Nadeau et al. 1999:529). It is likely that this difference in perception between the two groups is evidence of egocentric economic thinking. Anglophones are inclined to believe that they would be economically disadvantaged in a sovereign Quebec: 70% believe that the disappearance of their linguistic community is likely if the movement should succeed (529). It also seems logical that Allophones, as a result of Bill 101, would feel better-equipped to operate economically in a sovereign and presumably more French Quebec.

Turning now to the age cleavage, the generational explanation is that economic risk averseness (the motivating power of fear of economic loss) varies depending on the economic circumstances in which a generation is socialized. A low risk-averseness is the product of – and synonymous with – the development of post-materialist values (Inglehart, 1971: 991), which, research suggests, are more prevalent among militant sovereignists than federalists (Martin & Nadeau, 2002:148). The theory is basically that generations socialized in harsher economic circumstances will be relatively more materialist than generations socialized in easier economic circumstances (Martin, 1994: 346).

This leads us to consider the different economic circumstances in which successive generations were socialized in Quebec. As was mentioned earlier, the majority French population in Quebec in the first half of the 20th century was primarily rural, and very poor. Rapid economic development took place following the war, reaching a fever pitch between the mid 1950s and mid 1960s. At that point it peaked and then slowed down through the 70s and 80s (though only modestly when considered relative to the economic deprivation of the period prior to the boom, remaining relatively stable to the present) (350-1).

We would thus expect, according to this argument, that the pre-boom generation would be the most materialistic, followed distantly by generation X, with the echo-boomers nearly as post-materialistic as the boomers themselves. It is important to note that there is a huge disparity between the poverty of the pre-Silent Revolution era (which was marked by the depression and the war years), and that of the years in which generation X was socialized.

How does this correspond to the data? Survey data from 1991 (before the larger part of the echo-boomers entered the electorate) found that, controlling for identity (the psycho-social explanation), the pre-boomers were far more affected by concern with possible economic consequences of separation than either baby-boomers or post-baby boomers (Martin, 1994: 355). The difference between the boomers and post-boomers was far smaller, with the post-boomers somewhat more affected (Ibid.). This is generally supportive of the argument, although it is important to note that with only one survey it is impossible to establish conclusively that the phenomenon in question can not be due to life-cycle. There is a correlation with the respective generations’ level of support of sovereignty, but that does not prove causation, leaving the door open. As such, more research needs to be done to establish this hypothesis conclusively.

Turning to these other factors, it is interesting to note that for all three groups, the negative correlation between those people concerned with a serious economic downturn and who support sovereignty is statistically significant. Conversely, the correlation that emerges from looking at the beliefs of those who foresee a positive economic impact from sovereignty is only statistically significant for the post-boomers (356). This is the opposite effect of what the theory would have you believe. It suggests a life-cycle explanation deriving from the fairly widely held belief among Quebecers that separation could be promising economically in the long term (in 1995 48% expected gains in the long term (Martin & Nadeau, 2002: 152). Only post-boomers could really expect to benefit from a long-term improvement or even recovery in the economy (Martin, 1994: 351).

Additionally, it is very theoretically plausible that younger people would generally have more confidence in their ability to persist in difficult economic conditions, being more mobile (for example, due to a higher rate of people without dependents) and resilient. Applying the same logic older people (who are dependent upon retirement savings or government pensions (Blais & Nadeau, 1992: 93)), would have far less confidence in their own ability to “pull themselves up by their bootstraps” in the event of a serious economic recession, drastically increasing their risk aversion. This is logically an equally viable explanation of the 1991 survey results to what is put forward in the generational argument. The test of it will be whether or not the boomers’ risk aversion will increase as they hit retirement (a process that is beginning now).

Differences in regional voting can also be partially attributed to economic considerations, as was touched on in the previous section. Outaouais is located along the Ontario border near Ottawa, so the low level of sovereignty support is due in part to the nature of employment within the region. As 25% of the population works for the federal government (Monière & Guay, 1996: 241), they fear the loss of their jobs in a separate Quebec. This is due directly to the proximity of this area to Ottawa (229). Finally, Beauce, an overwhelmingly francophone area, provides another exception. It is mostly rural and borders on the American state of Maine. Beauce and the other border regions are less supportive of an independent Quebec because they fear the loss of benefits they derive from free trade agreements when these are renegotiated (242), as well as a change in their position relative to their neighbours.

Differences in regional voting can also be partially attributed to economic considerations, as was touched on in the previous section. Outaouais is located along the Ontario border near Ottawa, so the low level of sovereignty support is due in part to the nature of employment within the region. As 25% of the population works for the federal government (Monière & Guay, 1996: 241), they fear the loss of their jobs in a separate Quebec. This is due directly to the proximity of this area to Ottawa (229). Finally, Beauce, an overwhelmingly francophone area, provides another exception. It is mostly rural and borders on the American state of Maine. Beauce and the other border regions are less supportive of an independent Quebec because they fear the loss of benefits they derive from free trade agreements when these are renegotiated (242), as well as a change in their position relative to their neighbours.

Agential Factors: The short-term determinants of choice

Having established what structures determine the existence of a relevant choice, we are now able to address what factors influence how this choice is actually made during an election. This section is premised on the idea that elections should not be thought of solely as “neutral” processes “through which citizens simply register pre-identities and political understandings” (Cairns, 219: 1994), that in fact campaigns can have a significant effect, having the power to convince people to vote counter to, or in a more nuanced way, than would be suggested by simply compiling their social background characteristics. In support of this, in the 2000 election one in three Canadian voters changed their vote choice during the campaign (Blais et al.: 2002: 76). In Quebec there is reason to believe that while the dynamics of this variability are different, they still exist in some form. Howe deduces that this is the case because of the elasticity of opinion on each of the determinants of sovereignty support (1998: 32).

Mirroring and corresponding to the effects of partisanship on vote choice in Quebec (Clarke, et al.: 1996; Blais et al., 2002: 118), data suggests that the strong sovereignists (with a powerful identification to Quebec) and strong federalists (with a powerful identification to Canada) form two relatively unmovable[1] voting blocks (Howe, 1998: 53). For these individuals, sovereignty opinion translates directly into their vote choice; aligning with the corresponding sovereignists party (the BQ) or the traditionally federalist parties (the Liberals or Conservatives). As Howe puts it, “to the extent any movement is possible… it is only a section of the Quebec population that is likely to be affected. Those with strong Quebecois identities are apt to prove implacable” (59). Those with flexible opinions possess an identity somewhere in between that of the two extremes. As such, the extent to which a campaign can be effective is the extent to which it succeeds in affecting the opinions of these crucial voters.

What is the distribution of the voting population across these three blocks – (1) unmovable federalist, (2) unmovable sovereignist, and (3) those whose positions can be changed during a campaign)? Although independence is not the same as sovereignty, a recent poll on the flexibility of opinions on independence provides an approximation. In 2005, 36% of Quebecers stated that they could still change their mind in a vote on independence, including 34% of self-identified independentists, and 37% of federalists. This group of movable voters consisted mainly of Francophones and Allophones, with a smaller but still significant group of English speakers (Léger Marketing: 5) roughly illustrating the number of movable voters.

We have termed the factors being discussed in the following section “agential” in that they depend on the political agency of key actors within the system who have the power to affect the perceptions and opinions of the electorate. They attempt to do so in their own best interests. They are the “z factors” mentioned, but not elaborated on in the model developed by Pinard and Hamilton (1986: 226). The media, politicians, and voters all adopt different roles and operate within different political environments as Election Day approaches than what is typical (Mendelsohn & Nadeau, 1999: 64).

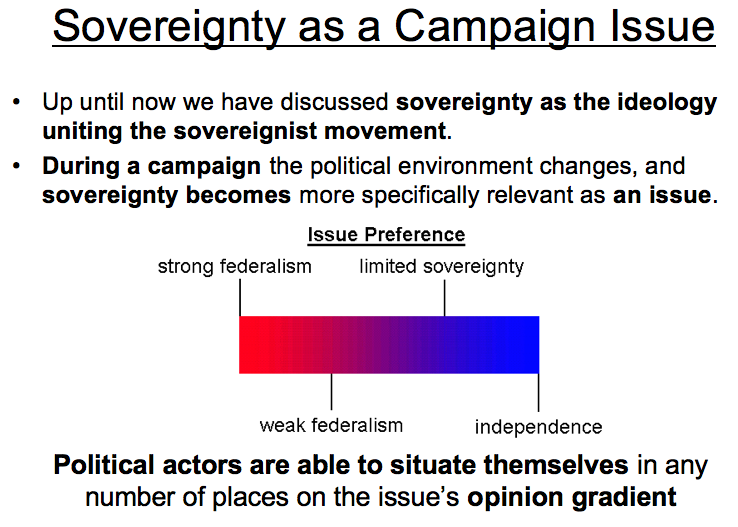

Looking at such short-term determinants of choice it is important to reconsider sovereignty as not a broad movement or ideological preference as was the case in the previous section, but as a campaign issue relative to which political actors (parties, party leaders, and voters) situate themselves. As an issue, sovereignty is not dichotomous: political actors are able to situate themselves on a gradient from identifying with a strong association with Canada on one end, to complete independence on the other, with any number of positions in between.

We will begin this section of our discussion by looking at the effect of party leaders and the parties themselves, and then turn to the media – which to a large extent acts as a filter between these agents and the voters they are targeting. Finally we will discuss the voters themselves, and the nature of their agency in federal elections in Quebec.

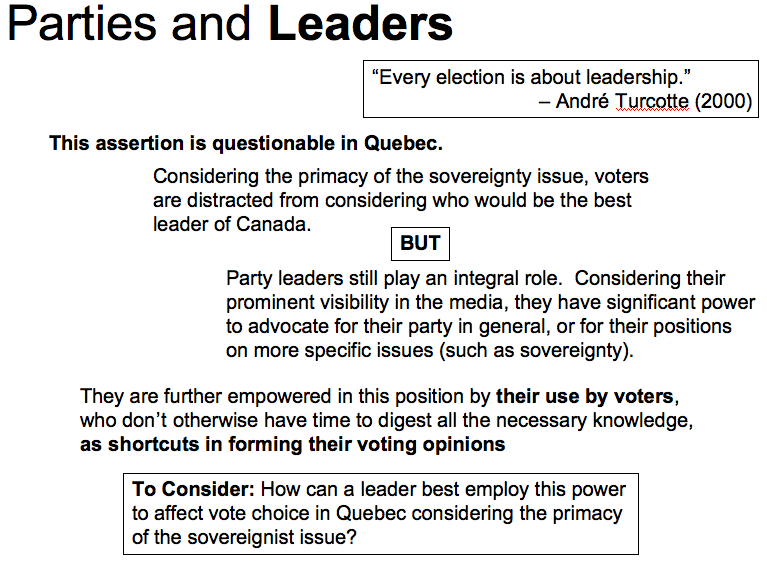

André Turcotte has said that every election is about leadership (2001: 281) as it is during the general elections when leaders attempt to persuade the Canadian voter that they have the qualifications to lead this country. Because Quebec is so dominated by the sovereignty issue this is far less the case. While a leader certainly needs to prove a base level of competence, his or her ability to lead the country is far less salient than their ability to advocate for a particular position on sovereignty. They are thus still highly important still possessing significant power to change voter opinions during elections, as they do in Canada in general (Brown, 1988: 729). This power stems from their access to voters through the media and through their party’s infrastructure, to advocate for themselves and their agendas; their power to do this is bolstered or crippled by their social background characteristics and regional affiliation with which key constituencies of voters will either identify or not.

Before further exploring this it is important to understand that leaders draw much of their influence from their being used as a shortcut in opinion formation for voters who do not have the time or the capacity to digest all campaign and political information that is relevant to making an informed choice, but still intend to vote (Cutler 2002: 469). It is critical to understand exactly what it is about leaders that cue such voters in a way that informs their ultimate vote choice (Brown, 1988: 73). Employing a series of open-ended questions, Steven Brown and his colleagues found that there are four grouped categories on which the electorate judge leaders: (1) politically relevant personality traits such as competence, dynamism, and integrity; (2) non-political traits (for example, personality, sociability etc.); (3) social background and political positions (e.g., “he is French Canadian”); and (4) their political skills and demonstrated good judgments, particularly in prominent past episodes. They match these traits to a prototypical conception of an ideal profile for a leader, and are on that basis affected in their vote choice (Brown, 1988: 753). A leader who very closely matches their ideal will be trusted to accurately reflect their opinions on the issues (or in Quebec, the determinants) and will thus attract votes. Therefore, in a campaign it is the prerogative of a leader to identify what possessed traits the flexible voters will most and least relate to, and project or play down those traits accordingly.

A highly salient trait in federal elections, and especially in Quebec, is regional affiliation. Fred Cutler asserted generally that “geographic distance between a voter and party leader has a strong effect on electoral choice,” (2002: 478). He points out that Canadians have traditionally been hyper-sensitive to the regional affiliation of party leaders, “particularly on distributive issues — which neighbourhood to tear up for a highway, where to put the toxic-waste dump, where to build a prison, an airport, or a park, whether to allow offshore drilling, where to disburse patronage.” He argues that localism may be an effective orientation for the voter in trying to predict a legislator’s preferences.’ Whether or not this is correct, the empirical findings can be viewed as confirmation, and a generalization, of the well-trodden “friends and neighbours” effect (Cutler, 2002: 480). This applies very poignantly to Quebec as its citizens are regionally united as “friends and neighbours,” in a manner of speaking, by their nationalist feelings. In fact, in 1993 André Blais and Richard Nadeau advanced a model with a high degree of explanatory power regarding federal election outcomes focusing on (1) the rate of unemployment and (2) whether or not a leader is from Quebec (787). They found specifically that the Liberals get on average 13 percentage points more votes in Quebec when their leader comes from Quebec, a strong enough boost to, with the bandwagon effect, typically push the party into office (780).

We have seen to a degree that vote choice is influenced by voters’ ability to identify with a leader regionally, but this can be applied to broader characteristics. Women are more likely than men to vote for female candidates, and in the United States it has been proven that black voters are more likely to vote for black candidates (Cutler, 2002: 468). More significantly, it follows that Francophones will be more likely to vote for a Francophone candidate, and since the Anglophone block of voters is generally set in their vote choice for the Federal party, it also follows that a party benefits Quebec by putting forward a Francophone leader.

Turning now to the leadership debates, evidence drawn from data collected over the last 30 years suggests that they have been a major factor in influencing vote choice. David Lanoue asked whether the 1984 debates translated into increased vote share for Mulroney (1991: 62). He found that public opinion polls showed a 10-point swing in favour of Mulroney in Quebec in the aftermath of the French Debate (54). The fact that there are separate debates in French and English is important to note as it seems fair to assume that the French debates are primarily viewed by French Quebecers – the group, as mentioned repeatedly, most important in defining election outcomes in Quebec. Leaders can tailor messages directly to this audience and express them through these debates. Furthermore, they put on display a leader’s ability in French which, as just discussed, will be salient for those who vote on the basis their ability to identify a leader as “like me.” That said, we must not give too much value to debates in determining which party will win the election. In both the 1988 and 1997 Canadian elections we saw that a leader may win the debates, but lose the election (Gidengil, Blais, Nadeau, & Nevitte, 2000: 4).

Turning now to the leadership debates, evidence drawn from data collected over the last 30 years suggests that they have been a major factor in influencing vote choice. David Lanoue asked whether the 1984 debates translated into increased vote share for Mulroney (1991: 62). He found that public opinion polls showed a 10-point swing in favour of Mulroney in Quebec in the aftermath of the French Debate (54). The fact that there are separate debates in French and English is important to note as it seems fair to assume that the French debates are primarily viewed by French Quebecers – the group, as mentioned repeatedly, most important in defining election outcomes in Quebec. Leaders can tailor messages directly to this audience and express them through these debates. Furthermore, they put on display a leader’s ability in French which, as just discussed, will be salient for those who vote on the basis their ability to identify a leader as “like me.” That said, we must not give too much value to debates in determining which party will win the election. In both the 1988 and 1997 Canadian elections we saw that a leader may win the debates, but lose the election (Gidengil, Blais, Nadeau, & Nevitte, 2000: 4).

Considering this influence, how do leaders specifically affect vote choice through the sovereignty prism? A charismatic leader can play up or play down perceptions of unequal treatment of Quebec from the rest of the province. It is informative to consider the effect of Preston Manning in the early and mid-90s. Emerging in 1993 as the leader of the Reform party and advocating a resistance to substantive accommodation with Quebec (Jenkins, 2002: 219). In so doing he galvanized support for the new nationalist party of Quebec, contributing to the catapulting of the BQ into prominence on Quebec’s federal political scene. In essence, their policy positions on the issue of the status of Quebec within the federal system fed off of one another. This is a perfect example of leaders’ actions manipulating perceptions of unequal treatment in Quebec and consequently affecting their vote choice. Examples of leaders attempting to affect perceptions of the economic consequences of sovereignty abound from the national debate surrounding the 1995 referendum. Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin (the Finance Minster at the time) employed scare tactics, warning that a separate Quebec could not necessarily count on close economic union with Canada, and would have an “arduous” time being incorporated into NAFTA (Department of Finance, 1995). Finally, looking to identity, while it is not so dynamic as the other factors, Howe argues that the sizeable portion of Quebecers with a relatively weak national identity can be persuaded to place a higher priority on negative economic factors (1998: 54), following from the above discussion of prospect theory. Leaders are uniquely positioned, as was just established, to be so persuasive.

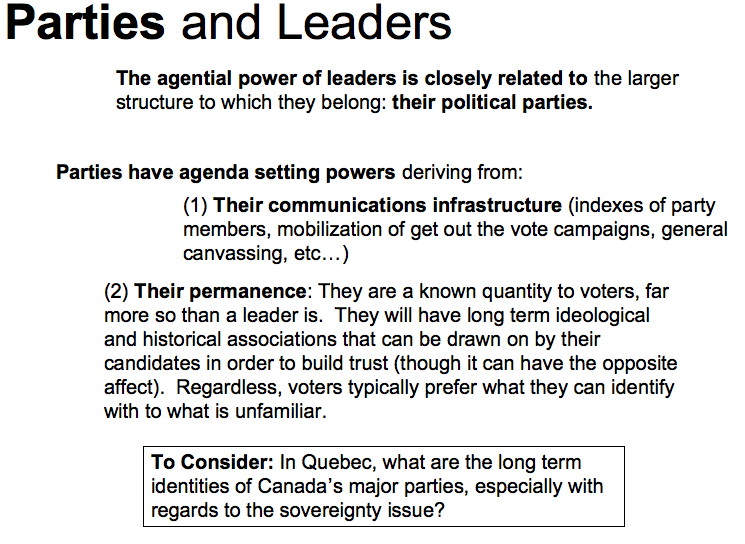

The agential powers of leaders, as we have seen, are very closely related to the larger structure to which they belong: their political parties. Parties themselves have agenda setting power deriving from (1) their communications infrastructure connecting them, and especially their leaders, to voters (as was discussed above), and (2) their permanence, allowing voters to form long term political identities in association with or against them. This long term identity derivatively affects perceptions of leaders who come to signify it. Without association with parties, leaders’ depth rarely extend below the current campaign, affecting voter confidence in them, and consequently causing their support to be much more fickle (Campbell, 1985: 30).

The long term identities of Quebec’s major parties, when considered in conjunction with the long term determinants that were discussed above, have profound implications to voter preference in federal elections. The BQ gains support that is predominantly French-speaking not because these voters are concerned about language, but because the Francophones are more likely to be primarily attached to Quebec and to feel unequal recognition from English-speakers in Canada, and thus to be in favour of independence. They also gain consistent support from the most intense Quebec nationalists (Howe 1998:59). The two main federalist parties, the Liberals and Conservatives, are supported by some Francophones and a vast majority of Anglophones because of the attachment these segments feel to Canada. Francophone support of federalism will also increase if their perception of unequal recognition decreases. Further, voting in Quebec is strongly influenced by voters’ perceptions of the consequences of independence to economics. Fluctuations in sovereignty support are most likely to occur as a result of altering expectations of the economic results of independence, and/or changing the view that Francophones receive unequal treatment. Attempts to alter national identification will likely be ineffective, as this is a long term, often permanent disposition (31).

Currently, the three parties mentioned are positioned distinctly on the issue of sovereignty, with the Conservatives filling the void between the liberals on the stronger federalist side, and the BQ on the sovereignist side.

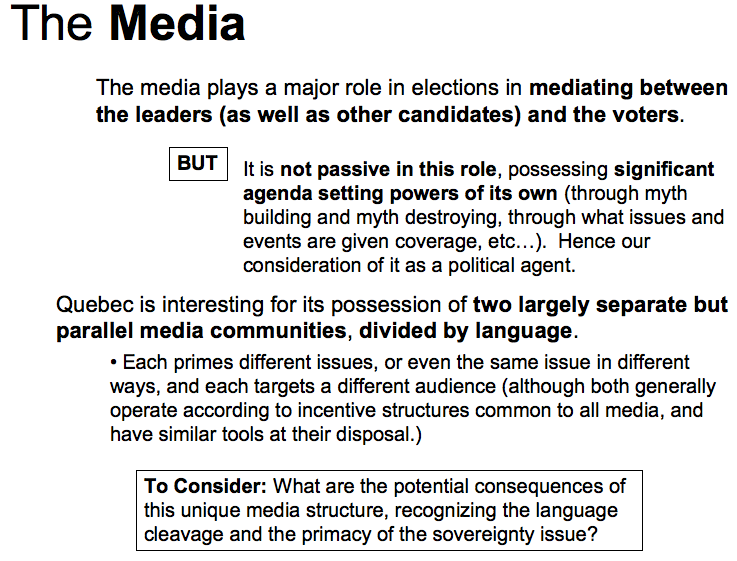

The power of the media to affect vote choice derives from their unparalleled access to voters and their role, especially in the case of televised media, as the primary transmitters of political information to them. What is important to note is that it is not passive in this role (Fournier, 2002: 65), and has its own agenda in how it presents political information, especially during a campaign period (Blais et al., 2002: 35), and through the tone of its coverage, has significant power to affect public opinion (Mendelsohn & Nadeau, 1999: 72). Voters make their political evaluations of leaders and their parties based on “media-reported individual performance” (Turcotte, 2001: 288): editorial discussions, political columns, nightly news and newspaper coverage.

Media is unique in Quebec for the existence of two parallel systems differentiated by the language of their coverage and their viewers. Considering that, as we established above, variability in vote choice exists primarily in the Francophone community, the French-language media is central to defining federal election outcomes in the province.

Voters have a distinct status within this framework of analysis. Voters form the electorate who ultimately decides who wins and who loses elections, and this voter choice is the central theme of the paper. They are the intended recipients of the manipulative efforts of the other political agents. The agency of the voters themselves must be emphasized. Their choice is not always so simple as to be based purely on their first order preferences, relatively easily identified and targeted by the other political agents above discussed. Voters can exercise their agency in a different manner through strategic voting. A strategic vote is “for a party [or candidate] that is not the preferred one, motivated by the intention to affect the outcome of the election… [It is] based on preferences and expectations about the outcome of the election and on the belief that one’s vote may be decisive” (Blais et al., 2001: 344). A strategic vote requires two conditions: (1) the vote must be cast for a party that was not the first choice party, and (2) it must be motivated by expectations about the likely election outcome (344). Strategic votes in a plurality system are generally made on the basis of the closeness of races in the voter’s riding, but could also include considerations about the party’s chance of becoming either the government or the official opposition (345).

Election studies suggest that in recent years strategic voting was not very important. In 1997, strategic voting was about 3% of the vote both inside and outside Quebec (347). In the 2000 election, 3% of those outside Quebec voted strategically, while there was no discernible effect in Quebec (187). However, the lack of success of the NDP in Quebec may suggest that the indicators being used for strategic voting are misleading in that province. The NDP is a solidly federalist party in regards to a stance on Quebec sovereignty, and is ideologically similar to the BQ. It is highly plausible to suppose that there are many in Quebec who would naturally gravitate to the NDP for its marriage of those two traits. However, because a strategic vote is based on expectations about the outcome of the election, even those who might consider the NDP otherwise would face an overwhelming incentive to vote for the Liberal party if they were against Quebec sovereignty or for the BQ if they were primarily concerned about ideology. The highly polarized environment of Quebec seems thus to provide for a large degree of strategic voting potentially masked by the sheer improbability of NDP success in the province. In essence, though they may be a voter’s naturally preferred party for their marriage of a left leaning ideology and support for federalism, it would not even occur to the average Quebec voter to identify them as such. Further research required to establish this conclusively, matching voters with certain value priorities to their first order party of preference. This would allow a researcher to test the degree to which these voters must compromise on what might be their natural choice in order to protect a basic value (in this case federalism or a left leaning ideology) considering likely election outcomes.

What has now been constructed is a full causal model of federal vote choice in Quebec. This model has been diagrammed in Figure 1 (next page). To summarize, vote choice in Quebec is a two staged mechanism with two distinct sets of independent variables. The structural determinants (perceptions of unequal respect and recognition, national identity, and perception of the economic consequences of sovereignty) define a voter’s natural preferences on the issue of sovereignty. During an election period party leaders, the parties themselves and the media attempt to affect the voter’s natural preference and translate it into a vote choice that accords with their respective agendas.

The Refusal of Choice

A lack of political participation by any significant group has a strong inertial effect, doing nothing to challenge the status quo, and thus implicitly supporting it (Martin & Nadeau, 2002: 149). Political apathy is a lack of motivation to make political choices, and Putnam argues, is a consequence of low civic engagement (participation in collectivities and other social networks) (2000: 184). Civic engagement in the US changed dramatically over the course of the 20th century, increasing dramatically in its first two thirds, peaking in the mid-60s, and then declining through the rest of the century, plummeting in the 80s and 90s (185). While the US is not a perfect analogy for Quebec there is no reason to suspect substantial deviations beyond the following: Instead of civic-engagement increasing gradually through the first half of the 20th century, it would have remained at a low and constant level due to its undeveloped society/economy. The evidence that we have been discussing suggests that it shot up violently with the economic and social changes following the Second World War, peaking with the culmination of the Quiet Revolution, also in the mid-60s. From that point there is reason to believe that Quebec followed a similar pattern to the American experience as the factors that have caused the social isolation that is the root of especially political disengagement (263) (the decline of the presence of the Church in society, the increase in the presence of the television and other technologies that take people out of their local communities, etc. (Schneider & Stevenson, 1999: 192)) have been equally if not more relevant. They are potentially more relevant because symptoms of social isolation, such as higher rates of depression and suicide (Putnam, 2000: 262), are even more evident in Quebec than in the US. Quebec has the highest rate of teen suicide of all the Canadian provinces, as well as one of the highest in the world (Shaver, 1990). Causes that are cited for this include the Quiet Revolution and family breakdown, both major social upheavals that have occurred in Quebec since the 1960s which have drastically reduced the stability of the environments in which individuals are socialized (Ibid.).

While this low civic/political-engagement of younger people is partially explained by life-cycle, marriage and children exerting pressures to increase engagement, a review of studies in the US over time has proven that the level of engagement across different cohorts at the same stage of life has fallen very significantly (Putnam, 2000: 249) suggesting generation contributes as well. Looking at Canada and Quebec, since 1988 turnout has not declined in the electorate at large, but is confined to, and incredibly dramatic in, Canadians born after 1970 (Blais et al., 2002: 46). This decline across age demographics was more prominent in Quebec than in any other province (47). Statistical analysis proves that this can be attributed predominantly to generation (49), and ultimately to the fact that the youngest generations are “just less interested in politics than older generations” (61). If this explanation is proven to be correct for Quebec, the implications are dramatic. Conservatively, the progressively increasing political-disengagement of post-boomers has, and will continue to have a magnifying effect on the boomers’ and pre-boomers’ political voices. A more extreme interpretation would have it that the consequence of this political disengagement could be the breakdown of the sovereignist collectivity.

Ultimately it is difficult to say whether the sovereignists or the federalists would benefit more from the political activation of the young. Some deductions could be made from the state of the economy over the past 20 years, but there is little information immediately available on national identification and feelings of grievances within that age group. Especially considering the unknown quantities of how being socialized in a globalizing economy, or with the internet relates to opinions on sovereignty, any strong conclusions on this topic will depend on further research.

Discussion

Quebec often plays a key role in the final outcome of federal elections, and so a major element of the election strategy of a party with realistic governmental ambitions is that dealing with the province’s sovereignty. The electorate remains divided – in April 2006, 43% of Quebecers supported sovereignty, and 57% opposed it. Election strategies in Quebec must focus on sovereignty. The electorate remains divided – in April 2006, 43% of Quebecers supported sovereignty, and 57% opposed it (Léger Marketing: 2006). The success of the BQ depends on convincing voters to support sovereignty, while the Liberals and Conservatives must do the opposite. Our model establishes three structural determinants of sovereignty support for these agents to address, however the population of Quebec is not homogenous in its decision-making. There is a core group of voters with strong identities, either Canadian or Quebecois, who are not likely to change their minds. For the BQ in the 2000 federal election, 40% of its supporters expressed no second choice, indicating that they are probably a part of this group. For the Liberals and Progressive Conservatives, such individuals constituted 38% and 41% of their voters (respectively). Movable voters, with weaker identities, are the true battleground in elections. The federalist parties each had only approximately 20% of their supporters who had the BQ as their second choice; a full 57% of BQ voters expressed a federalist party as their second choice (Blais et al., 2002: 77). Although this is not a perfect indicator of actually movable support for sovereignty, it provides an approximation.

As was discussed previously, these movable voters are heavily influenced by their perceptions of unequal respect and recognition, and of the economic consequences of sovereignty. A successful BQ strategy in the next election will inflame the grievances of Francophone and Allophone Quebecers, by portraying the Conservative government as dominated by Western Canadian ideology, particularly on the environment and Afghanistan. The French debates, where Stephen Harper is at a disadvantage and the focus is on Quebec, is an ideal venue for this. It also must overcome the natural risk-averseness of many Quebecers, and present a persuasive case that sovereignty will carry positive economic consequences. The BQ must remember that movable voters evaluate the consequences of sovereignty differently and more critically than the truly devoted members of the movement (Howe 1998: 40), and so require a specially-tailored strategy.

The Conservative government faces a difficult challenge in Quebec in the next election, if current trends continue. Its environmental and foreign affairs policies have been very unpopular, and have been the principle reason from the Conservatives’ decline in Quebec voting intentions from 30% in May 2006 to 16% in October 2006 (Bryden, 18 October 2006: A11). The party will therefore most likely face the attacks described above in some form. Its success in the election of 2006 likely resulted from their promises of Quebec autonomy, which would have helped to alleviate perceptions of unequal respect. If their policies are deemed to have not continued in recognizing Quebecer’s interests, the Conservatives’ foothold in the province will be at risk. This is a particular risk now with the Liberals’ selection of Stephane Dion as their new leader, who is not only a truly Francophone Quebecer, but is also not associated with the sponsorship scandal. Hours after his convention victory in December 2006, 62 percent of Quebecers believed Dion was the right choice for the Liberal party, the highest of any region in the country (Clark & Laghi 4 December 2006: A1). This may allow the Liberal base in Quebec to be re-established. The Liberals’ Quebec strategy should use Dion’s status as a Quebecer as an advantage against Harper, and also capitalize on their far more Quebec-friendly environment policy. A clear position on Afghanistan is also sorely required for the Liberals. Finally, for both federalist parties a key strategy will be to portray the sovereignist option as a drastic personal economic risk, in comparison with the safety gained from the supposed economic advantages of Canadian citizenship.

To gain a general understanding of Quebec voting, sovereignty has been a useful shortcut. It is not, however, the sole factor. For some individuals, non-sovereignist opinions are combined with a vote for the BQ, and some Liberal and Conservative voters (approximately 20% in 2000, according to Blais et al.’s 2002 study) are willing to vote for the BQ as their second choice, particularly in the Conservative case. Although sovereignty is the main factor in general, it does appear that many voters may support the BQ because of its advocacy for Quebec. In 2005, even though only 43% of Quebecers supported sovereignty, approximately half expressed voting intentions for the BQ. Certainly, the BQ’s choice in the 2006 election to prime other issues more than it had in the past capitalized on this trend. More research is required, however, to fully explore this phenomenon in Quebec voting. For all parties in Quebec, understanding the motivations and behaviour of this enigmatic subset of the population represents a significant opportunity to break the electoral deadlock on sovereignty and gain critical marginal votes.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Archer, Keith, “Voting Theory and Its Applicability in Canada” in Joanna Everitt and

Brenda O’Neill (eds.), Citizen Politics: Research and Theory in Canadian Political Behaviour. Agincourt: Methuen, 1985, 29-46.

Blais, André, Elisabeth Gidengil, Richard Nadeau, Neil Nevitte. Anatomy of a

Liberal Victory: Making Sense of the Vote in the 2000 Canadian Election. Ontario: Broadview Press, 2002.

—-. “It’s Unemployment, Stupid! Why Perceptions about the Job Situation Hurt the Liberals in the 1997 Election”, Canadian Public Policy – Analsyse de Politiques, VO. XXVI, no. 1, 2000.

Blais, André, Richard Nadeau. “Explaining Election Outcomes in Canada: Economy

and Politics.” Canadian Journal of Political Science, 1993, 26[4]: 775-90.

—-.“To Be or Not To Be a Sovereignist: Quebeckers’

Perennial Dilemma.” Canadian Public Policy, 18, 1992: 89-103.

Blais, André, Nadeau, Gidengil, Nevitte. “Measuring strategic voting in multiparty

plurality elections”. Electoral Studies, 2001.

Brown, Steven D; Ronald D. Lambert; Barry J. Kay; James E. Curtis. “In the eye of the

Beholder: Leader Images in Canada.” Canadian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 21, No. 4. Dec. 1988, 729-755.

Bryden, Joan. “Liberals Would Fare Best with Rae, Poll Finds.” The Globe and Mail. 18 December 2006: A11

Cairns, Alan C. “An Election to Be Remembered: Canada 1993”. Canadian Public