Part II Three Crises of Value(s)

Chapter 7 The Global Financial Crisis: A World Unmoored

Key Takeaways

Re-Litigating the Credit Crisis:

The US was leading global growth as the G1 and centre of financial reliability. The UK had 14 years (56 straight quarters) of growth. Inflation was stable. The early 2000s were an age of terrorism-wary prosperity. It was a time of great expansion, technological progress, countries clamouring to join the EU, China joined the WTO but there were other signs of trouble, for example Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth was shifting public opinion, according to Carney. Nevertheless, faith in markets rather than the underlying assets reigned supreme. Risk was by-passed using masked pools. Although Carney didn’t see it coming (he was obsessed with the US dollar’s health), he notes that the 2008 – 2009 financial crisis nearly imploded the US financial system (Argentina-style 2002) with collateralized debt obligations (packages of risky subprime mortgages) and credit default swaps (insurance deals on those risky mortgages). Carney notes that there is a pattern, before the credit crisis there was the dot.com bubble where profitless firms listed themselves at immense valuations…Russian 1998 financial crisis, September 16th, 1992 Black Wednesday UK exits the Exchange Rate Mechanism…Black Monday: 1987, 1929…not everything that is labelled a bubble is a bubble however…but the big pop was the 2008 – 2009 global (US-centred) financial crisis and it’s not exactly just about CDOs….

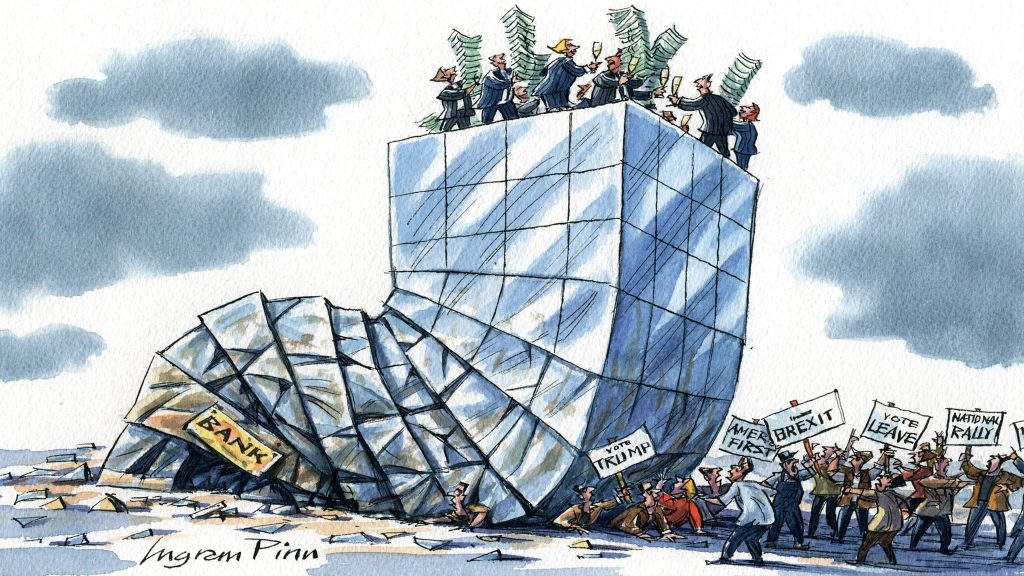

The world was about to become G0 i.e. no longer US-led, according to Carney.

To understand consider the Bob Hirst Doctrine:

Bob Hirst was a partner at Goldman Sachs who told Carney years prior that:

- if someone explains a concept or new innovation in finance the first time to you and it doesn’t make sense and then you ask for them to re-explain it and a second time it still doesn’t make sense, then you should run and or pick up your note pad in that meeting and just leave.

- The sales person is likely describing some financial alchemy or new version of the four most dangerous words in the English language: “this time it’s different” (page 155, Value(s)). Or possibly, the sales person doesn’t actually understand the alchemy in question themselves and they are too embarrassed to admit it.

- The only dumb questions in finance are the ones that are never asked….which is a problem.

- Carney recognizes that some financial pros do get lucky once in a while. Banks can sometimes copy and paste another bank’s strategy without understanding how that product actually works. But in a bear market, heads will roll or at minimum those responsible will run for the exits before the collapse….

Up in Canada, in August of 2007 the then deputy governor of the Bank of Canada Mark Carney got a panicked call from the President of Goldman Sachs Canada named James T Kiernan. The call was surprising,Carney knew Kiernan to not be a friendly chitchatter type. Kiernan was in fear that a crisis was brewing, the Canadian ABCP (asset backed commercial paper) market was in trouble: there were margin calls (a kind of run on the bank such that investors are demanding their capital to be withdrawn to safer havens) and liquidity back up lines were needed to be activated (capital injections from the central bank for example)….As the deputy governor, Carney’s first thought was ‘this was supposed to be a chill government post!’ In fact, Carney started out in commercial paper which is corporate debt that is short-term, matures in three to six months and is issued by successful large corporations.

CP helps with raising short-term capital for new projects for that associated corporation. It’s a sleepy space in finance and few people “got rich doing CP” (page 153, Value(s)). But there was now a $32 billion corner on Canadian ABCP…..which is minor compared to the $500 Billion government (provies, munies etc) debt and $1.5 Trillion in equities on the TSX at the time. Canadian ABCP was being abused by cowboys. Unlike Banker Acceptance (BA) which is issued by financial arms of various successful corporates with a stamp for a Dealer/Commercial bank and Banker Discount Notes (BDN) which are backed by Dealers/Banks like TD, BMO, CIBC, Scotia, RBC and NB, Canadian Asset Backed Commercial Paper were created by Bay Street cowboys who pooled credit card debt from the likes of Canadian Tire and then mixed that in with other risky debt ie subprime mortgages…It worked because it was opaque and the assumption with ABCP was that it would continue to be rolled forward and not redeemed at maturity which was typical as Carney says, 3 months to 6 months. But August 2007, Canadian Asset Backed Commercial Paper was about to stop making sense the Bob Hirst sense.

How this Canadian ABCP snowballed into a serious problem in Canada:

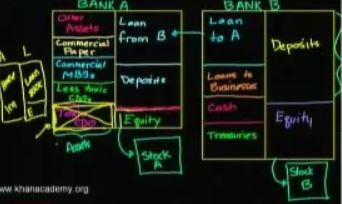

- There was this reformed approach / alchemy that pools of diversified assets were better, easier to sell than a single commercial paper from a single company such that large pools of credit card receivables could be packaged and then sold into a SIV (off-balance sheet structured investment vehicle) which are small shell companies that can disappear easily.

- That SIV (structured investment vehicles) would then issue commercial paper (short-term debt)…

- As long as the total interest paid on the credit cards (including the defaulting credit cards) was greater than the cost of the commercial paper, money was being made.

- The bank sells credit card receivables, gets cash and then issues new loans.

- The SIV owners make money on the spread (the bid-ask bargaining zone) between payments of credit cards and the interest on the commercial paper.

- Meanwhile investors would get returns on their capital allocations that were better than the interest from commercial paper of similar credit quality;

- They get paid to monitor and analyze the underlying assets to ensure “this all made sense.” (page 156, Value(s)). However, for Carney, a good idea that makes sense today ought to be re-evaluated regularly. In the case of these CP pools, there were sub-prime mortgages that wouldn’t come due in the 3 and 6 months intervals of the credit-card debt. This became murky and was why Kiernan needed to freeze margin calls.

Three Types of Risk Involved:

- 1st, the first type of risk to consider with Canadian ABCP is liquidity risk. Liquidity risk deals with the ability to sell an asset or borrow against its value. When the market is deep, taking cash out from individual investors is easy and doesn’t impact the overall price in the market. But when markets are thin, taking cash out can be much harder since there is less liquidity (thin) to have a two-sided transaction. The market can turn shallow quickly.

- 2nd, the second type of risk to consider with Canadian ABCP is credit risk where the underlying assets in the liquidity come due but there is widespread defaults (ie. the payments on the Canadian Tire credit cards aren’t being made). This can create a cascading impact on the inter-connected balance sheets of banks and trigger a financial crisis.

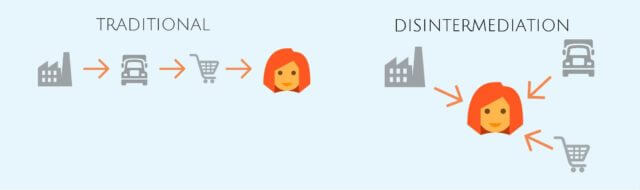

- 3rd, the third type of risk is disintermediation risk: Since ABCP was sleepy, the investors relied on the reputation of the SIV (off-balance sheet structured investment vehicle). But the problem was the SIVs relied on the credit track record of the bank managing the credit cards. While the credit rating agencies did their due diligence, there wasn’t a serious consideration around the quality of the underlying assets since the banks would issue loans and then put them in the market to be packaged away. The SIVs were far removed (ie. disintermediated) from the borrowers (ie credit card holders). There was a reliance on others in the system to ask the tough questions in good and bad times, and only when things went badly did true due diligence start. There was outsourcing of the moral hazard scenario. For Carney, the SIVS were acting like banks and the banks wanted the market to buy up their loans….

What Are Commercial Banks For: Carney details the function of commercial banks which is:

- To facilitate payments, the dumb pipes that make transactions possible…which is somewhat underthreat by new solutions…Stripe etc.

- To transform short-term liability (ie. deposits from customers which command interest payments) into long-term assets like (picking winners and losers) a loan to a small business or a mortgage which allows the homeowner to have a short-term asset and long term liability. This provides liquidity to customers by transacting at various maturities to provide efficiency in financial markets such that borrowers can obtain the lowest rate of interest based on their risk profile. The bank must necessarily mitigate the risk should depositors will all ask for their money at the same time which causes a run on the bank. The banks have deposit insurance which is calibrated to avoid moral hazard at the bank and there is the fail safe of the central bank can step in to be the lender of last resort;

- To connect savers with borrowers with good ideas to create economic growth: in other words, to allocate scarce resources to maximize profits by attracting savers seeking returns and giving to borrowers that can increase real value in the real economy.

The Great Disintermediation:

Carney argues that there was disintermediation between what banks are meant to provide and what they were providing. They forgot that they aren’t an end in and of themselves, although it seems a tall order for any individual to accept their role as servant in this context. The reality however is that many innovations were created to boost the financial bets between dealer to dealer transactions which were zero sum propositions dueling as “masters of the universe.”

Markets and Banks in a Collision Course:

Banks (relationship based specialized solutions) versus markets (transactional based standardized solutions): Banks manage relationships with the customers. Markets require standardization (low touch, limit orders) while banks love specialization (high touch and bespoke). Markets are transactional and connect savers and borrowers but markets aren’t relationship based.

For Carney, there were several issues at play in the crisis.

- First, banks were over levered as they moved towards short-term markets to fund their activities such as Repo, Commercial Paper and Money Markets.

- Second, banks used securitization markets again like Asset Backed Commercial Paper (ABCP) to do both the relationship side and the transactional side. Banks were taking specialized loans and packaging them as transactional pools/packages.

- Third, they moved into investment bank and proprietary trading which increased conflicts of interest with their client base.

- Fourth, Banks broke the system by taking the originate-to-distribute business model where specialization/relationships were packaged into standardized products that could be transacted as AAA rated because no one knew what was in them.

Northern Rock business model was this originate-to-distribute business model. Beginning as a building society, which issues mortgages fueled by payments from other mortgage lenders, Northern Rock pivoted into a regular bank in 1997. And their values effected value.

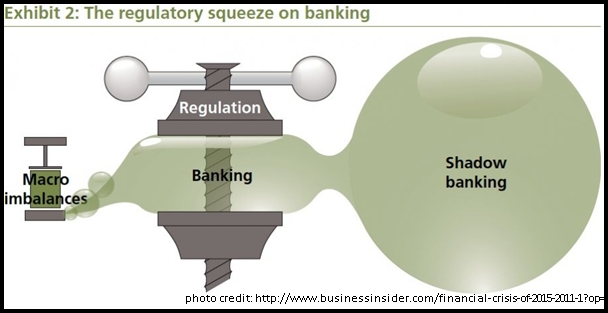

Rise of Shadow Banking and How Subprime Mortgages Impacted Canadian ABCP:

At the same time, markets moved into bank principally maturity transformation and credit intermediation through investment vehicles called the Shadow Banking system: SIVs, mortgage brokers, finance companies, hedge funds and private asset pools. Complacency drove a herd-like mentality that is common in finance generally. Then there was greed that began to bubble up as the bankers sought better returns. SIVs crammed into subprime mortgages into these ABCPs. ABCP made sense for a long time before it didn’t. As is well documented, packaging securities such as credit card debt, mortgage debt and other debt into new entities became commonplace and it became so murky you couldn’t tell what was in the underlying asset. The original idea made sense but then the bankers started to package subprime mortgage into these stable asset classes such as credit cards which are paid monthly while mortgaged take a lot longer to come due…. Creditworthiness relied on math that calculated the overall pools ability to reduce risk by having diversified pooling ie. the CAPM! BUT subprime was particularly screwed up in a downturn because strippers could buy 5 houses with Ninja Mortgages. The managers of the SIV’s balance sheets would put the assets to work by mimicking London and New York explosion of synthetic derivatives. The key was that these Canadian ABCP managers were selling synthetic derivatives to the London and New York firms and back this up with collateral from their ABCPs which meant that $32Billion in assets could balloon to be $200Billion in leverage.

Thoughts on Derivatives:

Carney wants to make clear that traditionally derivatives are considered an effective way of shifting risk as it is a bet on the underlying asset that is independent of that underlying asset. It allows the transfer of risk from one entity to another that is better able to handle that risk. Mesopotamia farmers were using derivatives on clay tablets to ensure that a farmer can agree to sell their crop in the spring to be sold in the fall for a set price. The farmer is protected by an uncertain outcome but the other side of that transaction could be harmed or benefited depending on how that season goes.

In Mesopotamia 5000 years ago (modern day Iraq) farmers were doing derivatives contracts on clay tablets to lock in the sale of their crop in the spring for that coming fall at a set price regardless of how the market price for that corp changed between the spring and fall. With interest rates, it is the same principle but with interest rates rather than the price of a corp being the risk that fluctuates.

Carney notes that by the mid-2000s, banks were no longer providing home loans based on their balance sheet of liquidity and capital constraints but rather on how quickly they could get that loan into the market by selling it into a securitized pool. By 2007, it wasn’t clear who you might call about the mortgages in question as they were pooled haphazardly regardless of the specialization and catering to the end customer. Since banks were keen to engage in risk averse trading, they locked in a derivative to protect against defaults on these potential pools should the mortgage default rate rise. But that only works if the supplier of the derivative can pay out the mortgage if it goes bad. Bankers became increasingly dependent on stacking more and more risk on top of itself. If the derivative supplier defaulted well then there was also as for collateral known as margin (Credit Default Swaps). More risky the position, the more collateral was required.

For Carney, the problem is that few people looked at the whole system. This is what happens when you have overconfidence in markets to solve these problems. Markets built upon Markets. Trying to solve market problems with more markets doesn’t always work. Or was it a crisis of moral hazard? Shareholders didn’t do the hard work. No one calculated the risks. The risks they thought they had off the balance sheet…The problem was that no single actor knew this was actually happening, really. And this was also widespread…..

Disintermediation between Finance and the Real Economy:

Significant GDP growth in the era was through these activities which were predominantly between banks and other institutions rather than between banks and the real economy…The regulators didn’t understand what was going on. The total value of the commercial paper market increased by more than 60% and the ABCP market increased by 80% in the three years prior to collapse…

Things Fall Apart:

Back to Carney’s personal story, in August 2007, the Canadian ABCP market was going to collapse even though the underlying assets were relatively balanced to the liabilities. The Commercial Paper investors wanted their assets out as there was a subprime crisis brewing in the US and the SIVs had pooled subprime mortgage into these ABCP. Unfortunately, it turns out that these assets had been pledged as collateral for credit insurance. The credit insured was able to collateralize up to 10 times the actual assets. London firms were holding $200 billion in Canadian credit exposures on underlying assets that were only $32 billion in value. The wider screwup was about $600 billion which was more than half of Canada’s GDP in 2007….These folks were just the start of a global crisis across the US, UK Europe….The market value of the subprime mortgages was under pressure and credit funds were now suddenly talking about pricing based on the underlying assets (objective value) rather then the market price / value of the assets (subjective value).

Therefore, those holding credit insurance from Canadian ABCP asked for more collateral, but the only way the ABCP could provide more collateral was if they issued more commercial paper and sold additional assets…this was precisely what the Canadian market didn’t want to do….

London banks knew if their margin calls weren’t met, they would immediately have massive exposures to credit on their balance sheet that they thought they had insured away. This explosion in the size of their balance sheet would be happening just as the investors and creditors started demanding answers about subprime mortgages. So a deal was possible merely because self-interest aligned not because of value(s)…..

The European Central Bank, the Governor of the Bank of Canada David Dodge, the Canadian department of finance, Henri-Paul Rousseau from Caisse de Depot et Placement du Quebec (Caisse) were able to convince the London and New York firms to stop their margin calls and prevent new issues of commercial paper. There was a freeze and the crisis was averted that summer. Carney hired Purdy Crawford to help prevent a catastrophe triggered by Commercial Paper. Investors eventually receive 90% of their investment rather than the 20% that was expected.

Global Financial Crisis:

In light of the Commercial Paper market near collapse in Canada there was a more well known crisis brewing with shell companies insuring enormous exposures. There was spiral as the markets were built on markets that assumed an upward future no matter what: leverage was more significant similar to the Canadian ABCP example. UK and US banks balance sheets went from 15x to 40x (169, Value(s)). Shadow banking had masked huge leverage and large contingent exposures. When margin calls couldn’t be met, the banks turned to money markets to support their cash needs but they were also major purchasers of ABCP….There was no sensitivity analysis in place. The opacity, complexity caused even more panic than was properly required according to Carney. The damage in the end was 5x larger than the original subprime mortgage crisis. $200 Billion became $1Trillion.

The Disembodied Grows Faster than the Underlying Asset:

There was a clear disintermediation between the general economy in the banking system. Overtime the banking system was no longer serving in the interest of connecting borrowers with lendersMid-level Traders would hedge out, so they would stretch out risk to the future. This was disembodied work. When bankers become disconnected, the LIBOR setter became obsessed with the number and not the underlying system.

Short-Termism:

The value of the short-term was everything, the future didn’t exist. The ethical foundations of finance are weak. The financial community cannot see the consequences of their actions the way a teacher or nurse does with student and patients respectively.

Investors were seeking to sell the risk on, until there were several layers of disconnection. On the way up value was disembodied, on the way down value was further warped.

They turned to the state and self interest was manifested. The crisis was painful because we didn’t have the chance to fix it.

Five lesson of crisis management during a financial crisis:

- The market can be wrong longer than you can stay solvent: no one agrees with objective value doesn’t work in a crisis. When markets collapsed, and the underlying assets were only worth 25% of what they were labeled then the banks holding those securities would be insolvent. So what was a liquidity problem became an insolvency problem over night.

- Hope is not a strategy: a plan beats no plan. Searching endlessly for the best is not realistic. When Carney was the head of the Bank of England, he expected “Remain” to win the Brexit vote however his contingencies building a play book for what could go wrong but not every possible scenario. It was better to have a bill insurance policy. This included ensuring the commercial banks preposition conlaterall with the Bank of England in order to underwrite the whole contingency. This enable the BoE to lend at least $250B to the banks, and it was the 4 times the size of the entire lending market to UK house holds the previous year. During the Brexit crisis, Carney was able to say “we are well prepared for this”

- Communicate clearly and honestly. You can’t spin your way out of this. Canadians know that the Fed and the Bank of Canada communicate regularly and Ben Bernake would be informing the BoC.

- There are no libertarians in financial crises, or no atheists in a fox hole: crises reveal the markets fail points. There was a call to shut the hedge funds down! According to the CEO, Lehman brothers was crazy. AIG was saved. Carney focused on the Canadian banks, they were the last stop before a barter economy. However much like a smoker Smoking in bed causes a fire, you would be worse off if you actually let the house burn down because adjacent properties might also catch fire and burn. The failure of one bank caused another bank. It had to be done quickly.

- Importance is Massive Action: resilience, reassurance is essential and the public need to be calmed by overwhelming force. What if the Bank of Canada didn’t act because the Harper government was not willing to act as they were in an election campaign? Carney needed to show that we would react overwhelming, and in coordination with the BoE, the Fed on an interest rate 50 basis point cut off. We needed a plan. In the case of letting the person who smokes in bed die, you bring on the risk that other houses might burn down in your effort to provide him that useless lesson since he is now dead. Better to let him live and teach him the dangers of smoking in bed.

Closure on the Canadian ABCP Story:

When investors asked what’s in these pools of Canadian ABCP, the bankers( who were one step up from branch level) explained that they couldn’t disclose the source. When the crisis erupted, those same bankers who sold the cowboy products to those same investors had to provide “no opinion on the matter” and explain this was tough luck burning relationships permanently.

The Washington consensus was flawed: Alan Greenspan had seen irrational arguments based on the fact that what he done had worked for the last 40 years and he did think he could lean into a bubble. Greenspan’s was partially wrong that some oversight. He was shocked that his expectations were dumbfounded. He didn’t address the expectations of a global market. Greenspan did rely on the self interest of markets. Greenspan felt that he had 40 years of experience that suggested too much government intervention is suboptimal.

Emergency G20 Meeting:

At the meeting Brazilian Finance Minister Mantega complained about the stupidity of Lehman Brothers….Bush showed up and admitted he was wrong, and asked that central banks and finance ministers back and support the US in solidarity. Bush won the room. Mario Draghi told Carney after the meeting was over, that in 1990, Mikhail Gorbachev was asking Mario Draghi for advice, which Drahi took to be a very bad sign at the time. Bush was desperate like Gorbachev. The world had moved from G1 to G0. Could the US restore faith in its financial systems? According to Carney, only if they rediscover their values…..

Before closing this chapter, I’ve added my notes from the Rotman Macroeconomics course attributed to Professor Dungan at UofT.

“

Post-Lehman: What Happened and How the Monetary Mechanism Has Changed

What Happened in the US – Very Simplified

- Highly risky mortgage debt was issued in US (also some European countries)

- Mortgage approval was split off from mortgage holding – a major incentive to approve excessively risky mortgages for the commission while not having to face the risks (Not having ‘skin in the game’)

- Moreover, the mortgages were ‘securitized’ – packaged into securities that were supposedly highly diversified and which got credit ratings far in excess of their true riskiness

- Banks in the US were eager to acquire these apparently safe but high-yielding assets in a scramble for returns when otherwise the long-short rate differential was very low

- The US has thousands of small banks at the local level that are difficult to regulate closely and that find it difficult to diversify widely.

- When Lehman failed, the market for the mortgage-backed assets dried up – the value of these assets was clearly diminished but there was no way to unload them or to value them accurately.

- Moreover – banks were required to ‘mark to market’ their asset values

- As a result, many US banks were potentially insolvent – they stopped lending to virtually everyone. (“Credit rationing”)

- This, and rates hitting zero, have changed US monetary policy instruments in a major way – see FRBSF ‘Economics Education

- For decades, the relative stability of the ‘money multiplier’ was taken for granted; it changed over time with the technology of finance and monetary operations, but the changes were generally smooth.

- With the post-Lehman meltdown in the US, commercial banks began to hoard reserves – fearing for the soundness of their assets and the risks of any further lending.

- In addition, the Fed could now pay interest on excess reserves – a source of risk-free return further helping soundness.

- The US Federal Reserve has supplied billions of new reserves to the system but, multiplied by a much reduced money multiplier, there has been relatively little growth in the true ‘money supply’. While reserves have exploded, the money multiplier has imploded.

- Much of the ‘inflation fear’ stemming from the Fed’s ‘adding hundreds of billions of dollars to the money supply’ does not recognize how the money multiplier has also shifted down. Most of the Fed’s supposed money creation has gone to excess reserves.

- Much of the ‘inflation fear’ stemming from the Fed’s ‘adding hundreds of billions of dollars to the money supply’ does not recognize how the money multiplier has also shifted down.

- The Fed’s job will be to take back the extraordinary reserves as the subprime toxic debt slowly unwinds and a more normal money multiplier is gradually re-established. (See (Optional) ‘Supersize Fed…’)

Why was Canada largely spared?

Canadian mortgage mechanisms generated relatively few excessively risky mortgages.

Canadian banks are large, diversified and more heavily regulated; they took on relatively little ‘toxic’ debt

Canadian banks have higher ‘capital’ ratios – the share of assets against deposits that must be the bank’s (shareholders) own equity. They were not as ‘leveraged’.

The Bank of Canada has therefore had to intervene little to assist the banks, and the money multiplier, base money and the money supply are all much more ‘normal’

See KrugmanFeb012010 on Canadian banks

What is Quantitative Easing?

- With short-term interest rates at zero, how can the US Fed further stimulate the US economy?

- (When rates are zero and inflation only 1%, real rates are -1%; Given the unemployment rate, the historical norm for the US would be real rates of -3% or -4%, but that is only possible when inflation is much higher and nominal rates do not hit the ‘zero bound’.)

- The response was ‘Quantitative Easing’ – in essence, trying to increase the money supply further even though there will be no additional effect on short-term rates.

- Under ‘Quantitative Easing’ the Fed bought a large amount of longer-term bonds (mostly gov’t); this should reduce longer-term rates, which affect longer-term Investment decisions.

- It also increases the reserves of the banks, making it more likely they will do more lending (increasing the money multiplier) because they have more ‘safe’ assets (their reserves at the Fed).

- Finally, it may increase expectations of inflation – but that works too, because it reduces the real rate of interest, both short and long.

- See ‘Economics Education’ (FRBSF)

New Monetary Tools:

- The other new tool of monetary policy is ‘forward guidance’ – letting the market know more concretely what the central bank intends to do; this can also help influence longer rates as they should respond to plans for future short rates.

- Now that the Fed has massive assets, and there are huge ‘excess reserves’ in the banking system, the mechanism for changing the key Fed rate changes (although the underlying principle is the same). The Fed has announced it will only sell off the assets acquired under QE when monetary conditions and interest rates become more normal.

- See Fed Interest Rate Mechanism after the Crisis – Journal of Economic Perspectives (JEPFall2015…(Optional))

Should Central Banks Target Asset Bubbles?

- After 2008 (and even before that) some analysts have accused central banks of not doing enough to deflate asset bubbles – even if tighter money would not otherwise be warranted by the level of inflation or the state of the overall economy.

- But an emerging current of thought is that other tools exist that can be used to attack asset bubbles without forcing restrictive monetary policy on the non-financial side of the economy – these are usually called ‘macro-prudential’ policies and include regulations limiting risk taking, forcing higher equity ratios, reducing margins, etc.

- See: Narrow Path – Monetary Policy & Asset Bubbles ECJun212014 and Low Rates vs. Financial Risks ECSep262015

Negative Rates and Helicopter Money?

- Very recently (Japan & Europe) some official rates and some market rates have gone negative. If inflation is negative, or expected to be so, this can still mean a positive real rate – so Japan is no surprise; but the negative rates have a bigger effect in Europe.

- Effectively, banks and other financial institutions are paying a ‘fee’ to work in electronic balances, rather than in literal ‘currency’ (which has a zero nominal rate); But there are limits to how far the negative rates can be pushed: See ‘Limits to Negative Rates’ ECFeb062016

- Discussion is emerging about ‘helicopter money’ – literally giving people more money; Effectively this also involves fiscal policy (taxing and spending by governments) and how it is financed.

See ‘Money from Heaven’ ECApr232016

- The most recent issue is whether central banks should increase their inflation targets (say to 4%) or move to a different target altogether (the most popular is ‘nominal GDP’). The reason for 4% is that then basic interest rates could be 5+% in ‘normal’ times and there would be room to drop rates a lot to counter a recession – given the zero interest rate limit.

See ‘When 2% is not Enough’ ECAug272016

”

End of Rotman MBA Notes

Analysis of Part 1 and Chapter 7

- Notice that the person who clued Carney into the Canadian ABCP crisis is someone he had worked with at Goldman Sachs, Jamie Kiernan. Networks matter. Networks shape how decisions are made. Hence the desire to take human decision-making out of central banking through first effort BitCoin-type solutions…which have their own problems etc.

- Carney is definitely hitting the nail on the head when it comes to system’s thinking versus individual thinking. We, as animals, aren’t very good at thinking about systems at all. And even if you give people a bird’s eye view of a system, they lose interest if there isn’t anything shareworthy, shocking or otherwise entertaining about that system. We talk about a single issue at a time in isolation. Our brains are unable to model the entire set of policy options. People who really dig board games are slightly better at this because they are exercising their systems thinking. Traders aren’t incentivized to think at the system level, neither are nurses, doctors, police, teachers etc we only address the breakdown in a system not when it is at risk of breakdown. And when it is at risk, there are strategic bets being made that it won’t breakdown versus something else that should be prioritized.

- This chapter is a nice re-examination of the oft Monday-morning quarter-backed Financial crisis which features prominently in film, television and academia.

- Good ideas make sense but then get abused and stop making sense, at that point self-interest sets in to running away while Carney fails to detail what should a banker do when something stops making sense?

- The Ben Bernanke analogy that it is better to wake the smoker in their bed and put out the fire before it engulfs the house and the neighbourhood is an illustrative analogy but it does not have predictive power in how might the financial crisis play out absent the government bailouts. This is particularly evident in the clue Carney leaves that the overall size of the subprime mortgage crisis with more like $200 Billion and not the $1 Trillion that it ended up being. If the crisis had an its course with the network of bankers saving themselves from total disaster then it is possible that the $200 Billion would have been self-containing and correcting or much less than the $1 Trillion price tag….we will never know whether a depression was truly avoided because it didn’t materialize partly due to the interventions of the government…the ultimately political discussions centre around known-unknowns. We know that there are alternative courses of action, we don’t know how those options would play out because we only have one version of events.

- The amount of regulatory oversight has always been limited by the fact that you can’t attract the best people to work in regulation because the best people are typically attracted by returns from hard work in the market.

- What happened with Canadian ABCP could have been used to warn other global actors about a heavily over-leveraged derivatives market.

- How has the Canadian GDP gone from 1.2 Trillion to 1.7Trillion in the last 10 years? If that is real, then who is getting all that benefit of the additional $500Billion?

- Wouldn’t it seem evident that people who have the least amount to lose in the medium term are those who expect to retire in the short term? If so, how do we ensure against, undue risks taken by those in the senior leadership who are typically command the resources of the firms they have risen up within? Bankers change jobs, get promoted, the decisions they make may not have material consequences until after they have left their role or even retired. How is asking for morality going to have a material change? The bankers didn’t even know what was going on, they were fixed on price in many cases. The mortgage lenders gave the stripper with the 5 houses because they were able to….where is the Big Short story in Carney’s narrative. Interesting to hear this CP story as it wasn’t the focus in my MBA which was well after the crisis….

- Citations Worth Noting for Part 1: Chapter 7:

- Mark Carney, “What are Banks Really For?”, Bank of Canada speech at the University of Alberta School of Business, 30 March 2009.

- Larry Summers, “Beware Moral Hazard Fundamentalists”, Financial Times, 23 September 2007.