PART 5 – The Love of Power

Chapter 25 – Changing

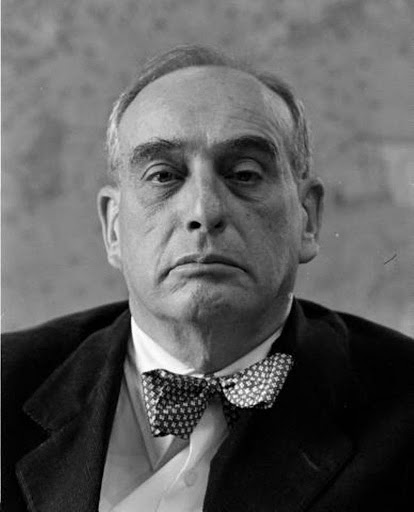

Moses’s need for power was strong and it was growing. He seemed to take pleasure in antagonising people who disagreed with his plans. He also started to act badly towards people who were nothing to do with his work. Sometimes because they were unable to fight back. An element of sadism seemed to have entered Moses’s character. He started to have physical encounters with people he knew could not fight back. He wasn’t content with ignoring opponents but was intent on destroying them.

A streak of maliciousness was becoming apparent as well. He ousted the members of the Columbia Yacht club from their clubhouse on a potential park site before they had time to consult with their members, merely because they asked for a few months delay to move their belongings. A judge agreed with the delay, but work went ahead. The clubhouse’s electricity was shut off. Then its water. By the time the injunction was put in force, trenches had been dug denying access. The clubhouse was then demolished even though the plans were not finalized for the park.

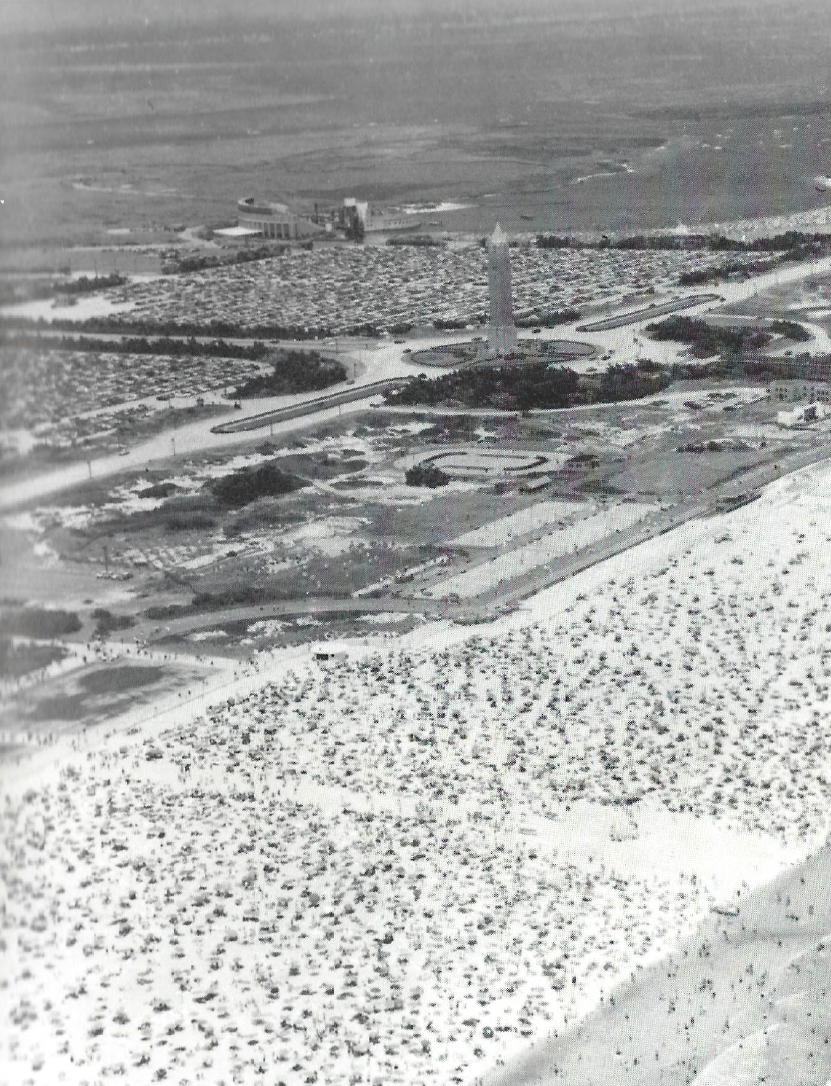

Moses’s methods were successful in that they intimidated people, allowing him to press on with his plans. He continued to create great works by creating new land and planting trees and flowers. His monuments were everywhere. The public cheered rather than moralized. The press were right back on side. His playground schemes were judged an unqualified success even though most of the playgrounds were placed in areas that needed them least. There were few in areas that needed them most, especially those containing black communities like Harlem, despite the evidence that the lack of well-run playgrounds was resulting in children wandering the streets and becoming involved in crime. Appeals were made directly to La Guardia but he was unwilling to cross swords with Moses.

Moses paid more attention to his expensive swimming pools. The success of these became a smokescreen to the failures of the playground program. His distaste for the black community was also evident here. Only white lifeguards and attendants were employed. At swimming pools in black neighbourhood, the water was kept significantly colder because Moses thought that this would deter blacks.

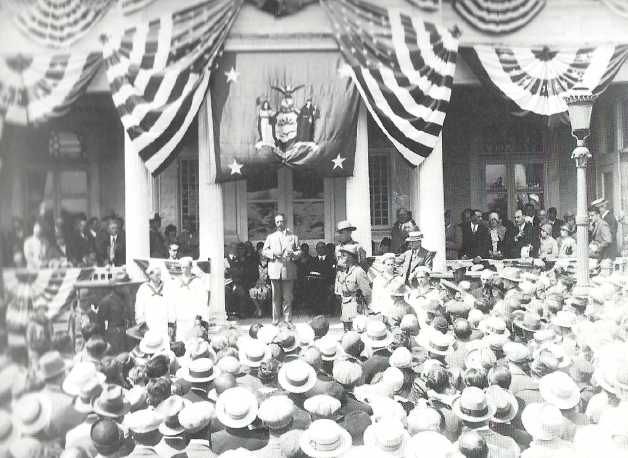

New parkways to were opened in 1936, but the traffic congestion returned in under three weeks. Moses’s solution was to build even newer parkways. The Triborough Bridge was also opened this year, to adulation from the public and the press. Soon after the opening New York City experienced one of its worst ever traffic jams. Again, Moses’s solution was to build more parkways. Again, the press agreed. But traffic growth was heading far ahead of estimates. It started to become clear that building more bridges and parkways increased the use of cars and this, along with the rise in car ownership, was the cause of the problem. There were calls to increase rail traffic to take the pressure off of the roads. However, Moses built the new $70 M Whitestone Bridge. It soon became jammed as well. Moses opened new city highways in 1939 and 1941. They filled up as quickly as the others.

Worst of all, Moses tore down the lively Third Avenue neighbourhood to make way for a ten-line highway which plunged Third Avenue itself into noisy darkness. Half the stores, restaurants and theatres were gone. Once it was a place for people, now it was a place for trucks and cars. The side streets, once the playground for children, were now too dangerous to play in. Third Avenue became a paradise for gangs, drunks and drug addicts, full of abandoned shells of cars, mattresses and rats.

Moses then turned his attention to his original dream, the Riverside Parkway heading north out of the city. The job had started in 1929 and over $100M had already been spent before being abandoned at the start of the Depression. Moses required $109M more. Moses found that the railroad owed the city $13M. This would provide Moses with a start. Moses needed to find a source of funds that the railroad could use to pay off the debt. He found this in funds available to build in the Grade Elimination Fund, set up to build bridges over railroads. Governor Lehman was persuaded to sign off the loan by promising that he would get the credit for the improvements. Moses got his money, but he needed $86M more. Moses scoured around for new funds to use and adapted his designs to qualify for them. The overall plans were labelled as Grade Elimination Plans to qualify for federal funding.

Although the fundraising was progressing, economies had to be made. This was made by drastically reducing the quality of work as it ran through poor areas as well as changing the route of the parkway to run straight through parkland. By these changes to the plan and strenuous fundraising, Moses need only $10M to complete his dream. He thought that this last pot of money would be the easiest to obtain, but it became the hardest. He attempted to interest Wall Street in a $10M bond issue, but the bankers would only release $3M. Moses worked to reduce the cost. As the PWA was to receive a new dispensation, he was able to get some funds from there, but he still had a significant shortfall. Then one of his engineers had a brainwave. They could build a smaller bridge, reduce the number of lanes, then strengthen and expand it when more fund became available. With this last economy, the funding for Moses’s dream was complete.

However, having the new parkway cut straight through a park – a park that was a considered one of the last great conservation areas of the city – created opposition. On top of this it was discovered that the original route was cheaper and would cause far less damage to the parks and connected waterfront. Moses refused to listen and pre-emptively began cutting down trees. Approval for Moses’s plan was given and by 1937 his dream was complete, but at a cost, during the Depression, of around two hundred million, skilfully hidden dollars and little of benefit to the poor and black neighbourhoods. As for the traffic congestion, this would continue to worsen. Despite these reservations, Moses’s reputation was at its zenith.

Analysis & Key Takeaways

- Mary did his finances…

- Moses was interested in grand design: not listening to the public. He was a kind of a Steve Jobs-type.