Chapter 18 – New York City before Robert Moses

Nowhere had the Great Depression hit harder than in New York City. More than one person in every three had lost their jobs. The rest were often paid a fraction of their former salaries. Malnutrition was rife. Children missed out of education. There was fear and terror of the future.

Tammany corruption within the city was endemic. Federal relief payments were being syphoned off. The test for employment was politics rather than need. By 1932, New York’s debts were over $1 billion, equal to the debt of all the other states combined. The reckoning for Tammany rule had arrived.

The city’s failures were not entirely due to the Depression. They were also caused by under-investment in crucial infrastructure. Corrupt employment practices had resulted in a lack of qualified technical staff. Public works were either lacking or substandard. The development of parks and parkways driven by Moses stood out even more starkly as an example of what could be done. Road connections, both by bridge and tunnel, between Manhattan and the mainland were seriously inadequate. New York City, in terms of the state of its parks, playgrounds, statues and other public provisions, was a crumbling disgrace.

Central Park was a good indication of the demise of the city. The idealist construction of the 19th Century had been destroyed by the Tammany governance. The zoo there stank from neglect, the animals either sick or malformed.

The city was surrounded by beaches, but their use by Tammany insiders restricted the general public to severe limitations. The beaches that were available were inhabited by lifeguards who couldn’t swim, or homeless people’s makeshift shacks.

During the Depression the parks started to fill with shack towns or “Hoovervilles.” There was a tremendous strain on housing and the slums were overflowing, with barely an acre of green space to provide relief. In 1932 there was only one playground for every 14,000 children. This did not prevent the construction of a casino in Central Park, at vast expense, by Mayor Jimmy Walker, who proceeded to use it as his own personal domain; somewhere to wine and dine his cronies.

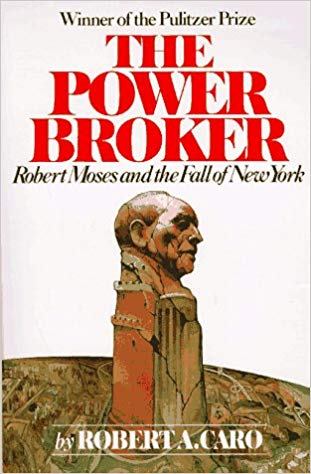

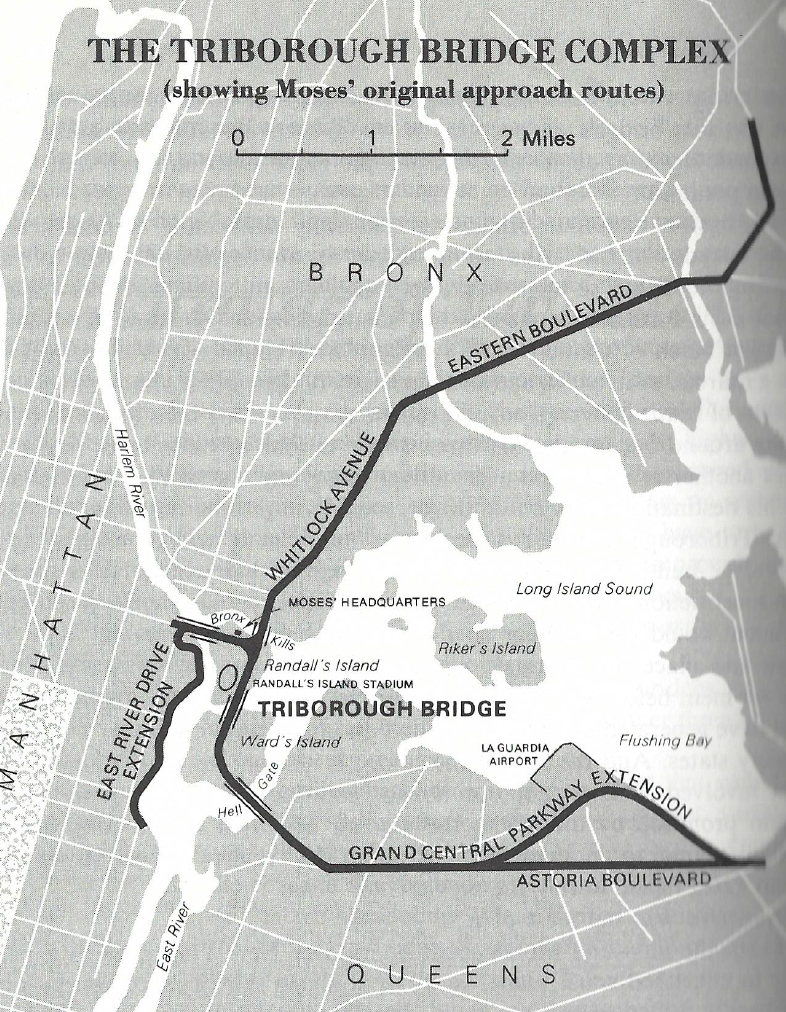

Moses had other things on his mind, namely, the construction of metropolitan parks and parkways, the Triborough Bridge, the Brooklyn Bridge and connecting roads to alleviate the city’s traffic problems. Moses was planning to connect Manhattan with the northern states, Long Island and New Jersey. It was the most ambitious city development plan in the world. But was it achievable?

Moses persuaded Roosevelt to allocate funds as part of the State Budget. The rest of the money however, was to come from the city. Roosevelt’s successor, Herbert Lehman, was a champion for Moses and set up a special commission with Moses as chairman to start the development. Some of the initial funds were syphoned off for other purposes and it was a struggle for Moses to persuade the funders. New York City meanwhile, was unable to pay its employees and was close to being declared bankrupt. However, in the summer of 1933, Moses was to bring fresh hope to his plans by running for Mayor.

Analysis & Key Takeaways

- The bridge is power, it’s the layers, public relations, and banks. Moses used the power of the bridge in order to leverage towards other projects;

- Any jurisdiction runs the risk of being mismanaged when the same people get re-elected time after time; it goes from democracy to kleptocracy rather rapidly. Mismanaging funds is often the act of screwing the future to help the present (since we don’t know what the future may hold).