Margaret Thatcher on the Hunger Strike & Anglo-Irish Relations

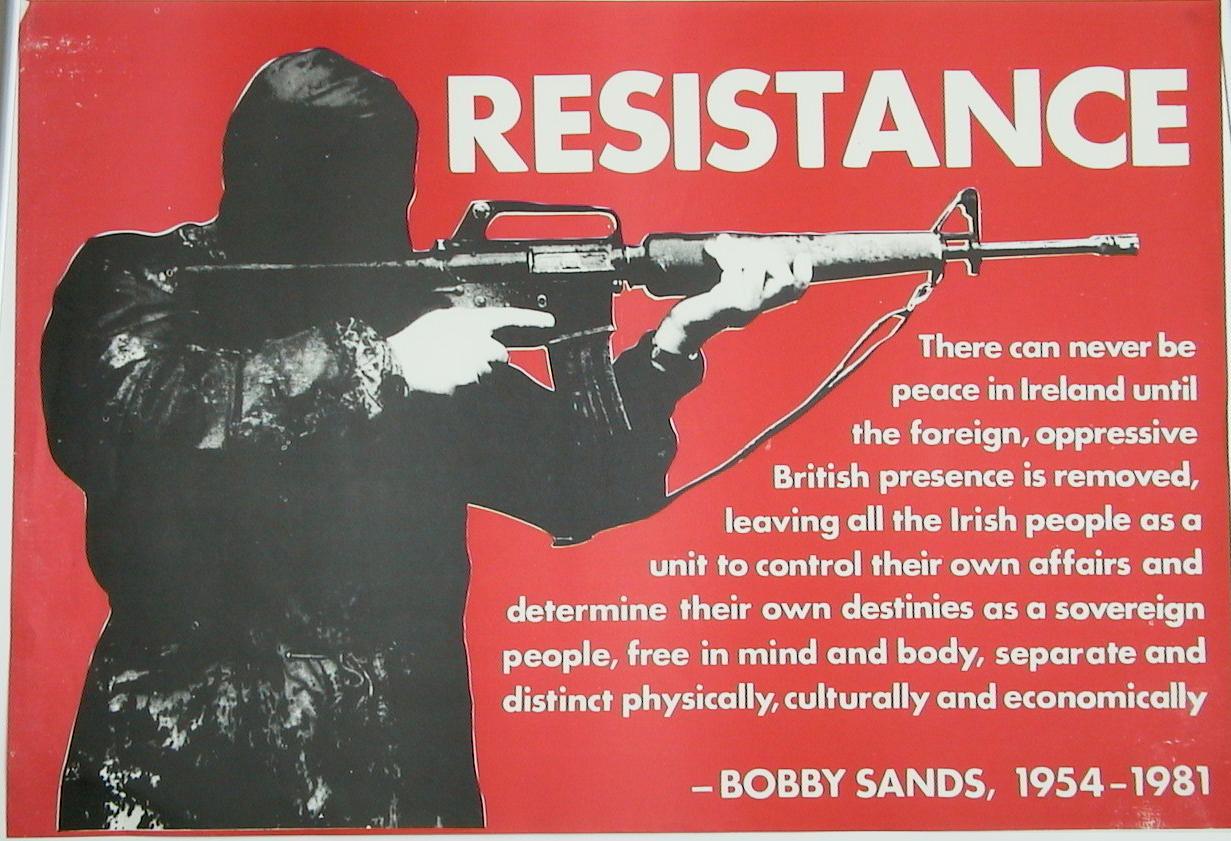

The hunger strikes of Republican prisoners inside Maze Prison were another issue that Thatcher stood firmly against. The Fianna Fail Party’s leader Charles Haughey had been previously accused of giving arms to the IRA. The IRA prisoners were referred to as a ‘special category’, which Thatcher philosophically disapproved of because they were not doing equal work as other regular prisoners. She resolved to end that special treatment for those prisoners. It was not retroactive, however. The hunger strike was caused by the prisoner’s desire to be considered political prisoners once again. The prisoners were forced to eat food. 10 of them eventually died: feeding tubes were brought in by the family’s recommendation. The loggerheads over this issue had already claimed many victims. Thatcher made no concessions to the strikers despite the appalling psychological torment that occurred. The Catholic Church had stood against the IRA meanwhile, the IRA was bombing stations on the mainland to protest alongside the hunger striking. Thatcher believed ‘no animal’ would ever bomb these people. Thatcher believed that “these terrorists were monsters!”

The hunger strikes of Republican prisoners inside Maze Prison were another issue that Thatcher stood firmly against. The Fianna Fail Party’s leader Charles Haughey had been previously accused of giving arms to the IRA. The IRA prisoners were referred to as a ‘special category’, which Thatcher philosophically disapproved of because they were not doing equal work as other regular prisoners. She resolved to end that special treatment for those prisoners. It was not retroactive, however. The hunger strike was caused by the prisoner’s desire to be considered political prisoners once again. The prisoners were forced to eat food. 10 of them eventually died: feeding tubes were brought in by the family’s recommendation. The loggerheads over this issue had already claimed many victims. Thatcher made no concessions to the strikers despite the appalling psychological torment that occurred. The Catholic Church had stood against the IRA meanwhile, the IRA was bombing stations on the mainland to protest alongside the hunger striking. Thatcher believed ‘no animal’ would ever bomb these people. Thatcher believed that “these terrorists were monsters!”

The Anglo-Irish Agreement, 1983-1985 period was marked by increase bombings on the mainland. The agreement was signed in 1985, November 15th between Thatcher and Garrett Fitzgerald. Thatcher pushed for rolling devolution in NI. The Irish Government had been thoroughly unhelpful during the Falklands War but Thatcher had to work with them to establish an agreement. The IRA continued to bomb England with even an American tourist being killed. Thatcher did not understand why the American Irish still sympathized with IRA activity. Irish were not clear in their negotiations over a peace accord, according to Thatcher. The agreement allowed for a cross-border conference about co-operation between the parties involved in the conflict. It was leaning towards convincing unionists into a power-sharing devolved government. The Labour Party opposed based on their principle of unification by consent. The Unionist NI opposed it because it gave the Irish Republic a role in governance for the first time. Thatcher felt that the Irish government was not doing enough to secure the border from terrorist who would cross over into NI. Thatcher once called the terrorists in the IRA to be ‘wiped of the face of the earth’. When Patrick Ryan, a Catholic priest turned terrorist, aided in the deaths of UK citizens Thatcher had difficulty extraditing him from Ireland to the UK. British governments have tried to gain support from the Irish Republican government against the IRA: that’s what the Anglo-Irish Agreement offered but it failed.

Margaret Thatcher on the Irish Republican Army

On the Ireland Republican Army

On the Ireland Republican Army

October 12, 1984: the Brighton Bomb was the closest to home for Thatcher. Preparing for a speech for the Conservative Party conference in the Grand Hotel, Thatcher was fortunate to be in her hotel room’s bathroom at the time of explosion. She escaped unscathed. Two MPs were killed among others, however. The Grand Hotel was badly damaged in the bombing. Some of the injuries were serious as well. Thatcher was extremely angry. The conference had not been cancelled as a sign of firmness in the face of terrorism. The ruthlessness of the attack had an emotional response from Thatcher: one of hate.

Terrorism is the calculated use of violence – and the threat of it – to achieve political ends. In the case of the IRA those ends are the coercion of the majority of the people of Northern Ireland. Their violence was not meaningless. Terrorists exist in both the Catholic and Protestant communities. Personal risk is made in the service of her country. The IRA is the core of the terrorist problem; their counterparts on the Protestant side would probably disappear if the IRA could be beaten, according to Thatcher. The IRA has plenty of support in areas of Northern Ireland. The ethno-cultural conflict between who should control NI has continued since 1922 when the Republic was created. Even in the Irish constitution, NI (Ulster = Protestant Ireland) is seen as part of Ireland.

Thatcher is a Unionist/Protestants and Methodist. The Conservatives have been committed to preserving the union. Ulster is a controversial word since it denotes Protestantism. Distrust and hatred have mounted far beneath the political surface of this conflict. The Conservative’s 1979 manifesto was to oppose the nationalist minority who are prepared to believe that majority rule would secure their right whether it took the form of an assembly in Belfast, or more powerful local government.

Nationalists/Catholics demand some sort of ‘power-sharing’ so that both sides can participate in the executive functions and a role for the Republic in Northern Ireland: Thatcher believes neither proposal is acceptable. North Ireland’s legal system along with Ireland is based on Common Law model of Stormont. Majority rule ended in 1974 when the NI government was integrated into the UK. Enoch believed that terrorists thrived on uncertainty about Ulster’s constitutional position: full integration would end that. Thatcher felt that devolution was superior; it would strengthen the union.