Chapter 50 – Old

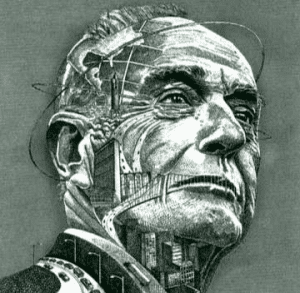

Moses’s mind was still active, but he had nothing to do. The months ahead drew bleak and terrible. The effect of powerlessness became apparent. The eyes became rheumy, the figure emaciated. A discouraged sigh would be emitted constantly. Moses still sat at his desk at Triborough, but no advice was sought. Soon his former aides were avoiding his office. Eventually, the reality of the situation became clear to Moses; he was being left to die.

Moses was reduced to pleading for a meaningful position. His old cronies tried to fight for him, knowing that their wealth was dependent on Moses having a say in development. Eventually however, everybody realised that Moses had lost all his power. Moses would continue to expound on his past successes, but now people would grow bored and leave. He was now quite deaf and his eyesight was failing. He was still a big man in presence, but the loss of power had a telling psychological effect; he was no longer intimidating.

His intelligence was still active and he still wrote about city planning. He had a city-wide housing program worked out, but the previous flaws were still obvious and now many commentators felt free to criticise them. His desire was to continue to build to save his reputation but the priorities had changed and his plans were ignored. His impotence turned into bitter frustration and violent rages. He could not sit still. He was always anxious to get back and could not get any solace.

There were bright spots. There were monuments and developments named after him. He was named “Man of the Year” in the early 70s by various organisations. He had continued support in some sections of the press. These bright spots however, became fewer and fewer. His name, once a symbol of progress, became a symbol of failure. He no longer had no public platform to express his views. He was asked to host a TV program. The program was a fiasco, partly due to the refusal to wear a hearing aid, resulting in the situation that he was unable to hear anything the other contributors were saying.

By 1972. All of Moses’s contacts were either dead or retired. Once he led battalions, now he had only his chauffeurs and secretaries. His name had disappeared from the press. Moses’s career was over.

Analysis & Key Takeaways

- Value of getting things done over wielding power to extract money or engage in corrupt acts: Moses was a cut above the both rich, arrogant and corrupt because he always fought opponents with joy and with the aim of expressing the ‘public interest’. He was consistently not held accountable by the electorate (for possible racism, prejudice, relocating the poorest in the name of engineering considerations i.e. the rich etc etc) becoming in effect the most powerful man in New York state for many decades. It was the fact that he was not elected, as a civil servant, he had the goal of wielding power in what he felt was unbiased. He did not value money or corruption through power. He valued the ability to get things done. And so he was closely aligned with the economic modernization of the New York infrastructure of the 20th century.

- And so he could get away with allocating power in what was in fact a very biased manner which he personally may not have realized was biased; and we cannot confirm every decision was close to objective because we don’t and never will have the data to show just how subjective he was relative to others.

- Moses tried to argue that the civilian roads were necessary to evacuate New York. He argued every case in order to gain more power. A totalitarian regime can have the will of a single architect the way a democracy cannot. People in a democracy do not sign on to having their own homes demolished for the greater good very often. This is the inherent frailty of democracy as a rather vague construct that doesn’t really exist in a serious way, because it is inimical to progress. Certainly Moses was at the heart of a totalitarian style and many politicians did not seem to mind that. Proof that democracy dies in darkness. Democracy must do better to counter-act the evidence that Moses “got things done” by also being as or more productive while also accommodating the interests and perspectives of a wider audience (the democratic advantage being crowd-sourced preferences).