Chapter 45 – Off to the Fair

In May 1959, the New York’s Citizens Union made an information request to Moses regarding the sponsors of the slum clearance program. Moses replied that the records would be available to any responsible body. This was to be one of Moses’s biggest mistakes. At this time, Moses was preparing for the opening of a new dam and he was often working sixteen hours a day so he may have been distracted. Also, his influence with the press may have assured him that nothing would come of the revelations.

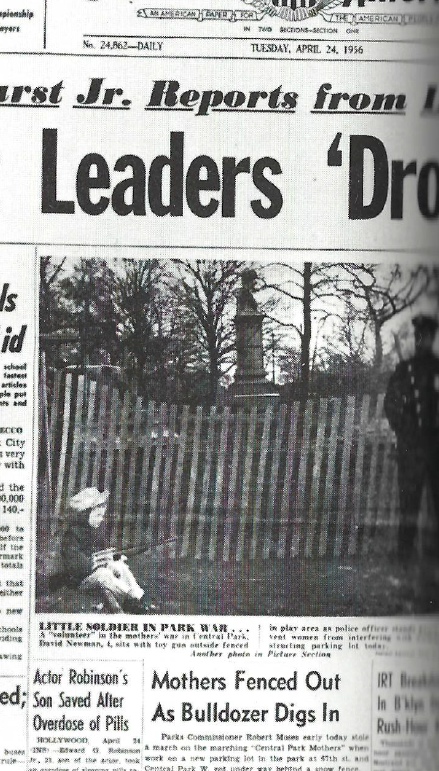

He tried to stall, but he could not stall indefinitely. Eventually the files had to be released and journalists were given access to Triborough headquarters. This was the first time in thirty-five years that any of Moses’s files had been made available. The files had been stripped of much crucial information, but the journalists continued to look and one day they found something.

They found an application by a potential sponsor for slum clearance who had links to gangsters. This scandal had something different. The press now had evidence of Moses’s links, however tenuous, to organised crime. A whole platoon of investigative reporters descended on the files. The deals between the Public Works Commission and shady sponsors, including politicians and Mafia bosses, at the expense of the people of New York, became clearer day by day, and Moses was at the centre of it.

The effect on the press on the publication of the revelations was profound. Previously cynical old hacks now became more friendly with the young investigative reporters, resulting in a press room at City Hall no longer cowed by the prestige of Moses and the Mayor. Publishers who had previously blocked stories about Moses were allowing them through. Even the Moses friendly New York Times was running front page stories linking Moses with scandals.

Moses continued to bombard publishers with complaints about the stories as well as seeking support from influential friends and contacts, but these efforts were starting to tip the balance against him. By the end of 1959 the truth about Moses was clear and his reputation was in ruins.

Moses however had one last thing going for him. Due to the amount of power and money he controlled through Triborough, he could not be fired. Reporters continued to ask Wagner what he was going to do about Moses, but Wagner was helpless and could only bluster. The showdowns between the Mayor and Moses were waited for with expectation by press and public alike, but they never came.

In the summer of 1959 however, a graceful way out was offered to Moses: The World’s Fair. Spending for this would be on an international scale. He could not keep his current city jobs if he was to be involved in the World’s Fair, but he could keep his lucrative Triborough job and through this retain control of over $2 billion worth of public works projects. The World’s Fair would give him a clean slate on a clean site. The Fair would rescue his reputation. It would be big news nationally and internationally. Moses thought it would be the project that would crown his career.

Analysis & Key Takeaways

- World’s Fair excites Moses.