A Defiant Defence of Diefenbaker: The Defense Crisis and Its Implications

One of the most tumultuous periods in Canada-U.S. Relations was the Defense Crisis of 1962 and 1963. In order to examine the American presence in Canada during that period, this article will accomplish four objectives. First, it will explain the background of the Defense Crisis. Secondly, this article will provide a historiographical analysis of John G. Diefenbaker. Thirdly, it will argue that the Defense Crisis led to explicit American intervention in Canadian politics. Finally, this article will defend George Grant’s significant contribution to analyzing this history and will reach the conclusion that Diefenbaker’s indecisiveness was not a product of personal tension with John F. Kennedy, but a product of an irreconcilable vision of Canadian Nationalism.

The historical background of the Defense Crisis begins on October 15th, 1958. On that day, the Canadian government authorized negotiations with the US government “for the acquisition and storage of defensive nuclear weapons and warheads” [1]. Bomarc-B Missiles were to be placed in North Bay, Ontario and La Macaza, Quebec to neutralize a surprise Soviet attack. The Canadian cabinet knew that “in taking the nuclear-[fitted] U.S. Bomarc weapon, Canada ran the danger of falling under greater U.S. military control in North American air defence” [2] given Canada’s obligations under NATO and NORAD. However, in response, Diefenbaker continued through five years of government to stall making a final decision to accept or reject the required nuclear warheads. Eventually, the government collapsed when the Minister of National Defense Douglas Harkness tendered his resignation in protest[3]. Among historians, it is widely accepted that Bomarc controversy was a key contributor to Diefenbaker’s political demise because it highlighted indecisiveness caused by personality problems. This article will suggest an alternate cause of this indecisiveness.

The historical background of the Defense Crisis begins on October 15th, 1958. On that day, the Canadian government authorized negotiations with the US government “for the acquisition and storage of defensive nuclear weapons and warheads” [1]. Bomarc-B Missiles were to be placed in North Bay, Ontario and La Macaza, Quebec to neutralize a surprise Soviet attack. The Canadian cabinet knew that “in taking the nuclear-[fitted] U.S. Bomarc weapon, Canada ran the danger of falling under greater U.S. military control in North American air defence” [2] given Canada’s obligations under NATO and NORAD. However, in response, Diefenbaker continued through five years of government to stall making a final decision to accept or reject the required nuclear warheads. Eventually, the government collapsed when the Minister of National Defense Douglas Harkness tendered his resignation in protest[3]. Among historians, it is widely accepted that Bomarc controversy was a key contributor to Diefenbaker’s political demise because it highlighted indecisiveness caused by personality problems. This article will suggest an alternate cause of this indecisiveness.

Most historians have a vastly different interpretation of Diefenbaker compared to George Grant’s interpretation of the lucky 13th Prime Minister. The question is how has this history been interpreted through the lenses of political biases? Before assessing Grant’s perspective – which plays a central role in this article – a historiographical analysis of the various competing interpretations of Diefenbaker’s behaviour must be taken into account. It is the next step in this article to contrast these differences and to suggest why such a divergence with Grant’s perspective exists on foreign policy. A general consensus among historians suggests that Diefenbaker was indecisive on accepting the nuclear warheads. What remains to be observed is each author’s claim to the source of this indecisive foreign policy.

A recurring pattern of pro-Liberal Party historians is to attack the character, not the ideological motivations behind Diefenbaker’s demise. Nash and Robinson both take this interpretative position. Among the most popular interpretations of the period is Knowlton Nash’s Kennedy & Diefenbaker: Fear and Loathing Across the Undefended Border. The books major fault is its overemphasis on the personalities of John F. Kennedy and John G. Diefenbaker. Nash first notes that the two world leaders backgrounds do not complement each other as Kennedy was a Bostonian Catholic elitist and Diefenbaker was a Saskatchewanian Protestant populist. Although Nash shares this descriptive tendency with most other historians, he characterizes Diefenbaker as a messianic demagogue full of exaggeration and infectious charisma. Nash also repeatedly calls him ‘insecure’, ‘irrational’, ‘obsessive’ and a small-town lawyer. This is juxtaposed with friendly adjectives calling Kennedy ‘young’, ‘ambitious’ and ‘witty’. For Nash, a series of altercations illustrates the international friction between the two nations. In January of 1961, Diefenbaker visited Washington and argued with Kennedy over sport fishing and the War of 1812[4]. Their personal tension were further exacerbated in May 1961, when Kennedy visited Ottawa, insulted Diefenbaker’s French and then asked for a ‘two-key’ nuclear warheads policy with Canada. Diefenbaker’s response instead was a peculiar proposition to accept nuclear warheads only during the initial phase of the supposed Soviet attack[5]. Nash’s conclusion was that as a consequence of personal clashes, both politicians grew to hate each other resulting in a foreign policy rift[6].

A recurring pattern of pro-Liberal Party historians is to attack the character, not the ideological motivations behind Diefenbaker’s demise. Nash and Robinson both take this interpretative position. Among the most popular interpretations of the period is Knowlton Nash’s Kennedy & Diefenbaker: Fear and Loathing Across the Undefended Border. The books major fault is its overemphasis on the personalities of John F. Kennedy and John G. Diefenbaker. Nash first notes that the two world leaders backgrounds do not complement each other as Kennedy was a Bostonian Catholic elitist and Diefenbaker was a Saskatchewanian Protestant populist. Although Nash shares this descriptive tendency with most other historians, he characterizes Diefenbaker as a messianic demagogue full of exaggeration and infectious charisma. Nash also repeatedly calls him ‘insecure’, ‘irrational’, ‘obsessive’ and a small-town lawyer. This is juxtaposed with friendly adjectives calling Kennedy ‘young’, ‘ambitious’ and ‘witty’. For Nash, a series of altercations illustrates the international friction between the two nations. In January of 1961, Diefenbaker visited Washington and argued with Kennedy over sport fishing and the War of 1812[4]. Their personal tension were further exacerbated in May 1961, when Kennedy visited Ottawa, insulted Diefenbaker’s French and then asked for a ‘two-key’ nuclear warheads policy with Canada. Diefenbaker’s response instead was a peculiar proposition to accept nuclear warheads only during the initial phase of the supposed Soviet attack[5]. Nash’s conclusion was that as a consequence of personal clashes, both politicians grew to hate each other resulting in a foreign policy rift[6].

One major historiographical problem in Nash’s interpretation is that he implicitly suggests the lack of friendship between leaders caused the disagreement on the Bomarc missiles. This is misleading. George Grant seems to have indirectly attacked the specific work of Knowlton Nash by stating that the media had “reduc[ed] issues to personalities”[7] for the purposes of the ruling class. Far too much credence is given to the friction between the two world leaders because of a simple truth; personal anecdotes are amusing and they give a simple but false explanation for the poor Canada-U.S. Relations during this period. Another problem with Nash’s interpretation is that in reality Diefenbaker’s policy was not endearing to either American presidents Kennedy or Eisenhower. Evidently, Nash overlooks the smooth personal relationship with Eisenhower despite serious policy disagreements between the Canada and American governments from 1957 to 1960. This misleading historical interpretation must be highlighted in order to demonstrate the flaw of overemphasizing personality clashes. In addition, it seems unlikely that Diefenbaker could position himself as leader of the Progressive Conservative party and then become what is described as a petty and irrational person upon meeting John F. Kennedy. There must be more to Diefenbaker’s indecision over the Bomarc missile. Nash does not differentiate between actions motivated by personal tension versus political tension.

Sharing a similar Liberal bias with Nash is another civil servant’s interpretation called Diefenbaker’s World. Basil Robinson openly admits to being a continentalist Pearsonian who witnessed Diefenbaker’s disintegrating leadership from within the foreign policy bureaucracy. As will be explored in detailed below, a continentalist is an individual who believes in a closely unified North America. Adding more substantive insight into this history, Robinson analyzes the underpinnings of Diefenbaker’s internal indecision by noting the dichotomy between two wings of the Progressive Conservative caucus. Howard Green and Douglas Harkness each represented competing wings of the caucus. Green was appointed the Secretary of External affairs and admonished nuclear proliferation while Douglas Harkness became the Minister of National Defense in 1960 and called for nuclear weapons on Canadian soil. While Green attempted to make international disarmament a reality, Harkness had to constantly make excuses for “the failure of negotiating with the United States and NATO authorities on nuclear warheads”[8]. Robinson also heavily implies that the Prime Minister was negligent and indecisive because of his natural tendencies and demeanour. This is flawed and serves Robinson’s personal self-defence from fundamentally disagreeing with Diefenbaker’s vision of Canadian Nationalism.

Sharing a similar Liberal bias with Nash is another civil servant’s interpretation called Diefenbaker’s World. Basil Robinson openly admits to being a continentalist Pearsonian who witnessed Diefenbaker’s disintegrating leadership from within the foreign policy bureaucracy. As will be explored in detailed below, a continentalist is an individual who believes in a closely unified North America. Adding more substantive insight into this history, Robinson analyzes the underpinnings of Diefenbaker’s internal indecision by noting the dichotomy between two wings of the Progressive Conservative caucus. Howard Green and Douglas Harkness each represented competing wings of the caucus. Green was appointed the Secretary of External affairs and admonished nuclear proliferation while Douglas Harkness became the Minister of National Defense in 1960 and called for nuclear weapons on Canadian soil. While Green attempted to make international disarmament a reality, Harkness had to constantly make excuses for “the failure of negotiating with the United States and NATO authorities on nuclear warheads”[8]. Robinson also heavily implies that the Prime Minister was negligent and indecisive because of his natural tendencies and demeanour. This is flawed and serves Robinson’s personal self-defence from fundamentally disagreeing with Diefenbaker’s vision of Canadian Nationalism.

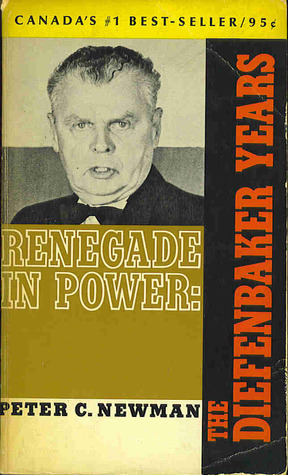

The more conservative leaning analysis, Peter C. Newman adds greatly to the interpretation of the growing Defense Crisis. Newman wrote Renegade in Power within several years of Diefenbaker’s fall in 1963. Newman took the necessary time in a balanced historical interpretation to focus on the philosophy that drove Diefenbaker to reject the rules of international subservience. For Newman, Diefenbaker believed in national building in the tradition of John A. MacDonald, although in a modern era of increasing continental interdependence. Diefenbaker was surprisingly left leaning on welfare policy and desired closer ties with Britain, which American continental interests despised[9]. Newman continually emphasized in contrast to the Nash and Robinson readings that the Canadian Nationalist rhetoric damaged the influence of the “continentalists in the American State Department who believe that what’s good for the U.S. us automatically good for Canada”[10]. “Diefenbaker never managed to make convincing his often-repeated boast that his anti-Americanism was actually pro-Canadian”[11]. Although both Newman and Grant agree that a clear vision of Conservatism was allusive, they both point to the institutions and entrenched structures that usurped Diefenbaker from power. The indecisiveness was political, not a product of irrational fool, but of serious discord with the rhetoric and the realities of Canada’s position in North America. It was not that Diefenbaker’s indecisiveness was a product of character, but a product of untenable principle.

The more conservative leaning analysis, Peter C. Newman adds greatly to the interpretation of the growing Defense Crisis. Newman wrote Renegade in Power within several years of Diefenbaker’s fall in 1963. Newman took the necessary time in a balanced historical interpretation to focus on the philosophy that drove Diefenbaker to reject the rules of international subservience. For Newman, Diefenbaker believed in national building in the tradition of John A. MacDonald, although in a modern era of increasing continental interdependence. Diefenbaker was surprisingly left leaning on welfare policy and desired closer ties with Britain, which American continental interests despised[9]. Newman continually emphasized in contrast to the Nash and Robinson readings that the Canadian Nationalist rhetoric damaged the influence of the “continentalists in the American State Department who believe that what’s good for the U.S. us automatically good for Canada”[10]. “Diefenbaker never managed to make convincing his often-repeated boast that his anti-Americanism was actually pro-Canadian”[11]. Although both Newman and Grant agree that a clear vision of Conservatism was allusive, they both point to the institutions and entrenched structures that usurped Diefenbaker from power. The indecisiveness was political, not a product of irrational fool, but of serious discord with the rhetoric and the realities of Canada’s position in North America. It was not that Diefenbaker’s indecisiveness was a product of character, but a product of untenable principle.

It could be argued then that the forces of continentalism overthrew the Diefenbaker’s Progressive Conservatives. With serious policy missteps regarding to the Coyne controversy, cancellation of the Arrow, growing monetary crisis, unabated unemployment rates, Diefenbaker’s defeat in 1963 can be attributed to many factors. This article, however, will present conclusive evidence that among the most significant factors was the American desire for regime change in Canada.

The Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 reopened the debate over nuclear warheads in Canada. For Kennedy’s Secretary of State Dean Rusk, “Diefenbaker’s ‘introspection and nationalism’ were the biggest problems in Canada-U.S. relations”[12]. On the Canadian side, continentalists like Sevigny believed that “the need for…a closer association with our NATO partners…[was made] very clear by [the] tragic Cuban incident”[13]. From the American perspective, the intense crisis proved resolutely that Diefenbaker was either indecisive or stubborn with regard to American security needs. Following the failure to swiftly declare ‘DEF CON 3’ on October 21st, 1962, the Diefenbaker government was the target of a replacement campaign that would allow American Cold War objectives to be achieved. Similar to Vietnam in October 1963, Canada required a discreet coup d’etat. In quick succession, the Kennedy Administration struck three strategic blows against the Canadian government to achieve that end.

The Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 reopened the debate over nuclear warheads in Canada. For Kennedy’s Secretary of State Dean Rusk, “Diefenbaker’s ‘introspection and nationalism’ were the biggest problems in Canada-U.S. relations”[12]. On the Canadian side, continentalists like Sevigny believed that “the need for…a closer association with our NATO partners…[was made] very clear by [the] tragic Cuban incident”[13]. From the American perspective, the intense crisis proved resolutely that Diefenbaker was either indecisive or stubborn with regard to American security needs. Following the failure to swiftly declare ‘DEF CON 3’ on October 21st, 1962, the Diefenbaker government was the target of a replacement campaign that would allow American Cold War objectives to be achieved. Similar to Vietnam in October 1963, Canada required a discreet coup d’etat. In quick succession, the Kennedy Administration struck three strategic blows against the Canadian government to achieve that end.

The first blow occurred with an incident of frankness, revolving around retiring NATO General Lauris Norstad; an American. On January 2nd, 1963, whether by accident or design, Norstad told reporters that Diefenbaker had not fulfilled his obligations under NATO regarding accepting nuclear warheads. This was an open attack on the Canadian government that would spark major controversy. Criticism in the Conservative caucus put Diefenbaker on unstable ground as indecisiveness seemed to give way to utter incompetence.

The next blow was the Pearsonian Re-Alignment on missile defence. On January 12, 1963, newly anointed Liberal Party leader ‘Mike’ Pearson decisively declared that he was ‘ashamed we accepte[d] commitments and then refuse[d] to discharge them”[14]. In a complete reversal of Liberal Party policy, the Liberal leader fulfilled the desires of the ‘Establishment’ by calling for the acceptance of nuclear weapons. The infamous about-face was the consequence of repeated consultation with the JFK. Many insiders “felt sure that Pearson had made a deal with Kennedy that in exchange for Pearson’s switch on nuclear warheads, Kennedy would help destroy Diefenbaker”[15]. As two Nobel Prize winning internationalists, Kennedy and Pearson had good personal relations, but far more importantly; Pearson had a malleable ideological preference for continentalism.

The final blow was a reaction to a miscalculation on the part of Diefenbaker. On January 21, 1963, Diefenbaker claimed in Parliament that a ‘rethinking’ had occurred between the leaders of America, Britain and Canada at the Nassau meeting. This was a crass attempt to justifying indecision concerning the nuclear warheads[16]. The implication of this gaffe was that a public denial in a U.S. Government press release was necessary and tremendously embarrassing. In essence, the Kennedy Administration had explicitly intervened in Canadian affairs in what would “deliberately foster an anti-American thrust in the tactics…[of[ the coming election campaign”[17]. This evidence of interference was openly accepted by future Liberal leader Pierre Trudeau who confirmed in the Cite Libre that “Diefenbaker was beaten by ‘les Hispters’ around Kennedy”[18]. The 1963 Diefenbaker campaign was had the best of his political career according to most sources, but it was not enough against the full force of the United States. The ultimate consequence was the collapse of Diefenbaker and re-installation of the Liberal regime. The nuclear warheads were brought into Canada immediately by Pearson’s new government.

The final blow was a reaction to a miscalculation on the part of Diefenbaker. On January 21, 1963, Diefenbaker claimed in Parliament that a ‘rethinking’ had occurred between the leaders of America, Britain and Canada at the Nassau meeting. This was a crass attempt to justifying indecision concerning the nuclear warheads[16]. The implication of this gaffe was that a public denial in a U.S. Government press release was necessary and tremendously embarrassing. In essence, the Kennedy Administration had explicitly intervened in Canadian affairs in what would “deliberately foster an anti-American thrust in the tactics…[of[ the coming election campaign”[17]. This evidence of interference was openly accepted by future Liberal leader Pierre Trudeau who confirmed in the Cite Libre that “Diefenbaker was beaten by ‘les Hispters’ around Kennedy”[18]. The 1963 Diefenbaker campaign was had the best of his political career according to most sources, but it was not enough against the full force of the United States. The ultimate consequence was the collapse of Diefenbaker and re-installation of the Liberal regime. The nuclear warheads were brought into Canada immediately by Pearson’s new government.

The most plausible conclusion for why Diefenbaker’s government fell is articulated by Sevigny: “…by choosing to listen to the dreamers in his entourage and discarding the opinions of the realists, John Diefenbaker committed his most serious mistake, one which broke up his party”[19]. From the evidence, Diefenbaker’s dream of Canadian nationalism assumed that NATO was an alliance, not an extension of American foreign policy. Pearson’s acceptance of the latter gave him the advantage of American influence. During the election of 1963, Diefenbaker tried to paint the Liberals as co-conspirators with Washington and that a vote for the Liberals would lead to nuclear war[20]. This did not resonate. However, there was some credence given to Diefenbaker’s nationalist position after U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara revealed that the Bomarc missiles were in fact designed to draw fire away from American cities without much regard for Canadian civilians below the aerial interceptions of a Russia attack[21].

The most plausible conclusion for why Diefenbaker’s government fell is articulated by Sevigny: “…by choosing to listen to the dreamers in his entourage and discarding the opinions of the realists, John Diefenbaker committed his most serious mistake, one which broke up his party”[19]. From the evidence, Diefenbaker’s dream of Canadian nationalism assumed that NATO was an alliance, not an extension of American foreign policy. Pearson’s acceptance of the latter gave him the advantage of American influence. During the election of 1963, Diefenbaker tried to paint the Liberals as co-conspirators with Washington and that a vote for the Liberals would lead to nuclear war[20]. This did not resonate. However, there was some credence given to Diefenbaker’s nationalist position after U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara revealed that the Bomarc missiles were in fact designed to draw fire away from American cities without much regard for Canadian civilians below the aerial interceptions of a Russia attack[21].

To recap, the article first explained the Defense Crisis of 1962 and 1963. Subsequently, a historiographical analysis of Nash, Robinson and Newman interpretations showed that Liberal historians attempted to focus on Diefenbaker’s character over the true source of conflict. Then, the evidence was examined showing the Kennedy Administration’s intervention in Canadian politics. The article will now address the unique historiographical interpretations proposed by George Grant. It will conclude that Diefenbaker’s political principles were his ultimate downfall.

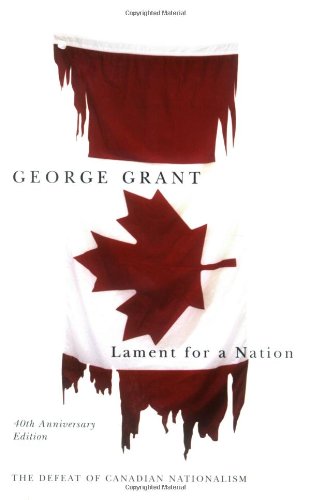

To understand more clearly the underlining framework of American manipulation, George Grant’s interpretation of Diefenbaker’s demise is most salient. George Grant’s Lament For a Nation is a direct reaction to the fall of the Progressive Conservatives in 1963 and its implications for Canadian Sovereignty. As part of his analysis, Grant states that “lamenting for Canada is inevitably associated with the tragedy of Diefenbaker”[22]. According to Grant, Diefenbaker’s political failure occurred because he challenged American continentalist, progressivism, and capitalist designs in Canada. The “prairie blowhard”’s downfall was rooted in his ideology of Canadian Nationalism. Part of the great disappointment from historians like Peter C. Newman was that Diefenbaker’s larger than life expectations fell well short of their mark. His “One Canada”[23] campaign rhetoric admonished voters against the Liberal desire for “a virtual forty-ninth state in the American Union”[24] but this socialist nationalism could not stand a chance in an already submissive Canada. In the end, the Bomarc missile fiasco was the tipping-point for an American coup d’etat that was in the making upon Diefenbaker’s rise to power.

To understand more clearly the underlining framework of American manipulation, George Grant’s interpretation of Diefenbaker’s demise is most salient. George Grant’s Lament For a Nation is a direct reaction to the fall of the Progressive Conservatives in 1963 and its implications for Canadian Sovereignty. As part of his analysis, Grant states that “lamenting for Canada is inevitably associated with the tragedy of Diefenbaker”[22]. According to Grant, Diefenbaker’s political failure occurred because he challenged American continentalist, progressivism, and capitalist designs in Canada. The “prairie blowhard”’s downfall was rooted in his ideology of Canadian Nationalism. Part of the great disappointment from historians like Peter C. Newman was that Diefenbaker’s larger than life expectations fell well short of their mark. His “One Canada”[23] campaign rhetoric admonished voters against the Liberal desire for “a virtual forty-ninth state in the American Union”[24] but this socialist nationalism could not stand a chance in an already submissive Canada. In the end, the Bomarc missile fiasco was the tipping-point for an American coup d’etat that was in the making upon Diefenbaker’s rise to power.

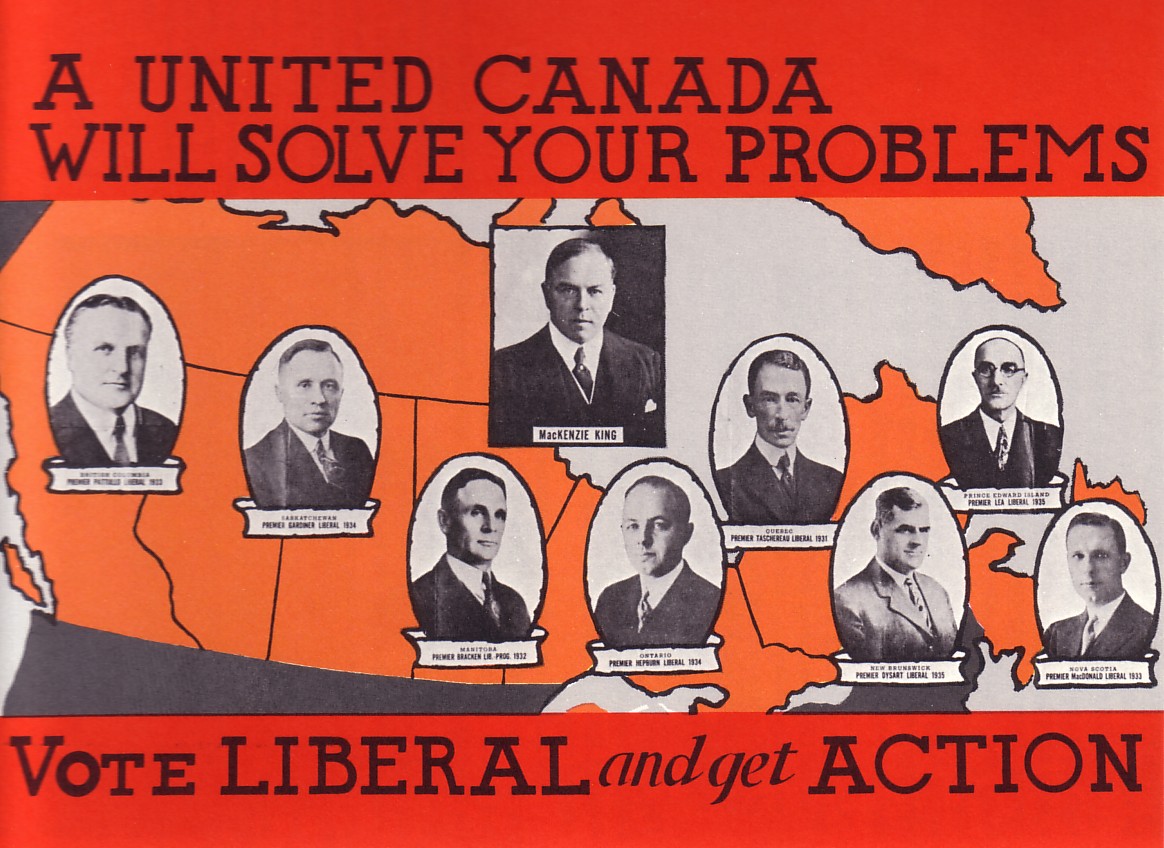

To elaborate on Grant’s argument, American imperialism relied heavily on the ruling class within Canada that had become continentalized in its views. These complicit Canadians were Diefenbaker’s adversaries. They include the King, St. Laurent and subsequent Pearson Liberal governments, as well as the entrenched continentalist bureaucrats such as Robinson and Pearson, in addition to the Central Canada’s anti-rural ‘Establishment’. Whether collaboration was intentional or accidental, the Liberal Party achieved hegemony during this period of the 20th century in part because of their acceptance of continentalism. Grant suggests that the march to American annexation was moving faster with Liberal pro-capitalist policies that “paid allegiance to the homogenized culture of the American empire”[25]. As a consequence of compliance, American universalizing and homogenizing free-market forces within Canada benefited the willing Liberals and disadvantaged the Saskatchewanian who was a populist that rejected the ‘Establishment’. Liberal rule was only interjected by a lapse from 1957 to 1963, which would be marked by a constant struggle between the three groups and the antagonist to their self-interest; Diefenbaker.

If this is true, as the evidence suggests, then this prairie, Protestant, orator served merely as a sacrificial lamb for American Cold War objectives in 1963. It also shows that the demise of Diefenbaker’s government was the tip of an iceberg that has inevitably sunk Canadian political autonomy. Diefenbaker was unavoidably wrong in contradicting the conventional wisdom of the American led progressive age. From Grant’s account, Canadian sovereignty was no longer viable since no alternative could be found, as demonstrated by Diefenbaker’s failure. In truth, Diefenbaker seemed to be an irrational protestor because a truly rational leader would have submitted to American desires. In his concluding optimism, however, Grant argues that the overwhelming forces of American imperialism left Canada as a satellite state destined to desire annexation for the betterment of Canada’s citizens[26]. The gravitational forces of progressivism, globalization and assimilation of cultural distinctions will ultimately result in the amalgamation of Canada into the American super-structure. This is Grant’s solace which Diefenbaker’s nationalistic rhetoric, so passionately, hoped to avoid but could not.

It would be erroneous to not mention, at this point, that George Grant was a leading proponent of Red Toryism. Compared to Liberal historians such as Nash and Robinson, Grant’s politics may too appear to mask biases. He may have simply developed a skewed perspective of Liberals who “led inexorably to the disappearance of Canada”[27]. However, his claims are justified because they can be qualified with compelling evidence. Both sides have a point, eh?!

It would be erroneous to not mention, at this point, that George Grant was a leading proponent of Red Toryism. Compared to Liberal historians such as Nash and Robinson, Grant’s politics may too appear to mask biases. He may have simply developed a skewed perspective of Liberals who “led inexorably to the disappearance of Canada”[27]. However, his claims are justified because they can be qualified with compelling evidence. Both sides have a point, eh?!

The goal of historians is to the piece together the past and synthesize it into tangible explanations of those events. It stands to reason that the Diefenbaker’s flawed personality, described by pro-Liberal academics, is a distraction from the actual source of Diefenbaker’s demise. Instead of the rampant character assassinations, historians should note that the causal arrow moves from Diefenbaker’s conceptualization of Canada to political indecision with regard to the Defense Crisis of 1962 and 1963. What becomes resoundingly consistent among historians is the sense that Diefenbaker was a disappointment. Intrinsic in their view is that he failed to achieve what his rhetoric so sincerely promised. Regardless of the bias of the various historians, there is a compelling argument within Grant’s work that may help change the commonly held perception about the outsider prairie populist and the Canada-U.S. relations in that period. The tragedy of Diefenbaker needs to be re-written to pay homage to his perilous and courageous attempt to carve out a sovereign nation despite forces more overwhelming than anything ever witnessed on this earth.

Work Cited

Diefenbaker, John G. One Canada: Memoirs of the Right Honourable John G. Diefenbaker: The Years of Achievement 1956 to 1962. A Signet Book: Scarborough, 1976

Grant, George. Lament for a Nation: The Defeat of Canadian Nationalism: 40th Edition. McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, 2005.

Nash, Knowlton. Kennedy and Diefenbaker: Fear and Loathing Across the Undefended Border. McClelland & Stewart Limited: Toronto, 1990.

Newman, Peter C. Renegade in Power: The Diefenbaker Years. McClelland and Stewart Limited: Toronto, 1963.

Robinson, Basil H. Diefenbaker’s World: A Populist in Foreign Affairs. University of Toronto Press: Toronto, 1991.

Sevigny, Pierre. This Game of Politics. McClellan and Stewart Limited: Montreal, 1965.

Smith, Denis. Rogue Tory: the Life and Legend of John G. Diefenbaker. MacDarlan Walter & Ross; Toronto, 1995.

Stursbeg, Peter. Diefenbaker: Leadership Lost: 1962-67. University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1976.

[1] Robinson, Basil H. Diefenbaker’s World: A Populist in Foreign Affairs. University of Toronto Press: Toronto, 1991: pp 106.

[2] Nash, Knowlton. Kennedy and Diefenbaker: Fear and Loathing Across the Undefended Border. McClelland & Stewart Limited: Toronto, 1990: pp. 76.

[3] Newman, Peter C. Renegade in Power: The Diefenbaker Years. McClelland and Stewart Limited: Toronto, 1963: 367.

[4] Nash, 96

[5] Nash, 119

[6] Nash, 100

[7] Grant, George. Lament for a Nation: The Defeat of Canadian Nationalism: 40th Edition. McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, 2005: pp 8.

[8] Robinson, 227

[9] Newman, 254

[10] Newman, 261

[11] Newman, 262

[12] Nash, 65

[13] Sevigny, Pierre. This Game of Politics. McClellan and Stewart Limited: Montreal, 1965.

[14] Smith, Denis. Rogue Tory: the Life and Legend of John G. Diefenbaker. MacDarlan Walter & Ross; Toronto, 1995: pp. 469.

[15] Nash, 255

[16] Smith, 466

[17] Robinson, 307

[18] Nash, 301

[19] Sevigny, 261

[20] Newman, 387

[21] Newman, 391

[22] Grant, 6

[23] Diefenbaker, John G. One Canada: Memoirs of the Right Honourable John G. Diefenbaker: The Years of Achievement 1956 to 1962. A Signet Book: Scarborough, 1976: pp. 21

[24] Grant, 13

[25] Grant, 7

[26] Grant, 94

[27] Grant, 6

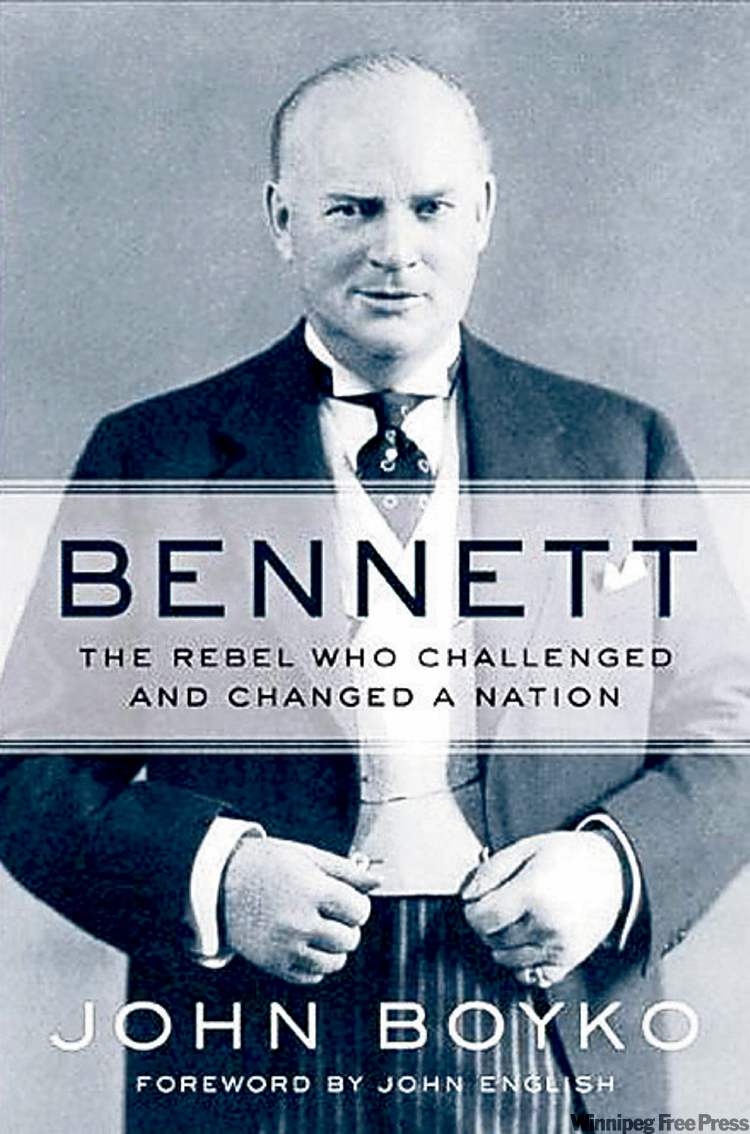

A fair amount of a party’s political success relies on good fortune. Steve Martin the comedian famously that ti……ming….is everything. If this is the case, R.B. Bennett was the most unfortunate Prime Minister in Canadian history. This essay will re-evaluate the Conservative party’s response to the Great Depression in Western Canada, accomplishing four objectives in order to defend Bennett

A fair amount of a party’s political success relies on good fortune. Steve Martin the comedian famously that ti……ming….is everything. If this is the case, R.B. Bennett was the most unfortunate Prime Minister in Canadian history. This essay will re-evaluate the Conservative party’s response to the Great Depression in Western Canada, accomplishing four objectives in order to defend Bennett The tragedy of Richard Bedford Bennett is rooted in a political philosophy that was no longer sustainable in the 1930s: the Liberal capitalist order. According to Ian Mackay, the classical liberal model was “hegemonic in Canada from the mid-nineteenth century to the 1940s”

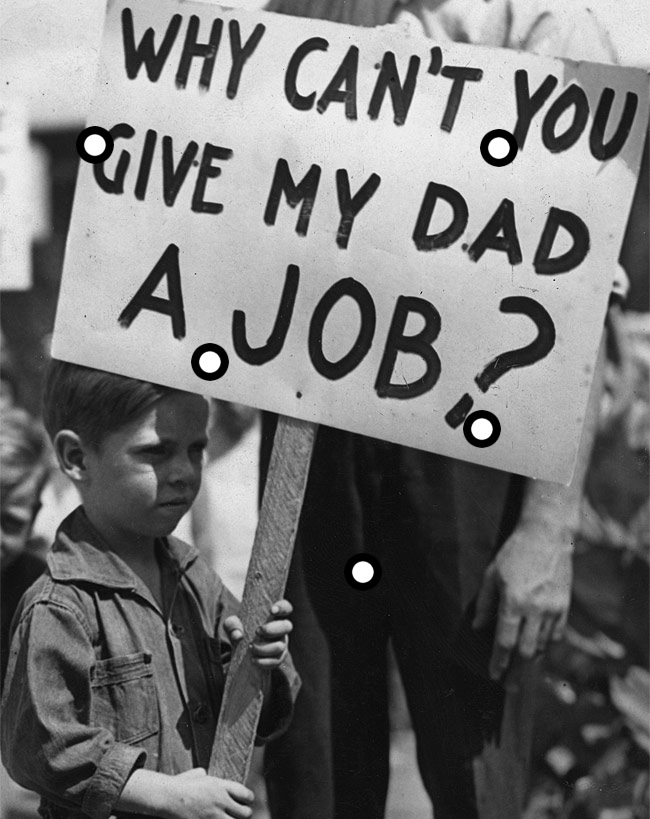

The tragedy of Richard Bedford Bennett is rooted in a political philosophy that was no longer sustainable in the 1930s: the Liberal capitalist order. According to Ian Mackay, the classical liberal model was “hegemonic in Canada from the mid-nineteenth century to the 1940s” The Great Depression of the 1930s transformed unemployment into the single most challenging threat to the liberal order. Throughout the 1920s, the urbanization process continued across Canada while in the Prairie West, agricultural expansion continued unabated. According to Struthers, “until the development of the Canadian West as a major wheat-producing region between 1896 and 1930, few economic links existed to bind the diverse regions of Canada together”

The Great Depression of the 1930s transformed unemployment into the single most challenging threat to the liberal order. Throughout the 1920s, the urbanization process continued across Canada while in the Prairie West, agricultural expansion continued unabated. According to Struthers, “until the development of the Canadian West as a major wheat-producing region between 1896 and 1930, few economic links existed to bind the diverse regions of Canada together” An unprecedented catastrophe occurred as two events crippled Western Canadian prosperity. The first event was the global phenomenon triggered by the US stock market crash of October 29th, 1929. The result locally was that the price of wheat fell 40 per cent on the price index while overproduction of wheat exacerbated the crisis

An unprecedented catastrophe occurred as two events crippled Western Canadian prosperity. The first event was the global phenomenon triggered by the US stock market crash of October 29th, 1929. The result locally was that the price of wheat fell 40 per cent on the price index while overproduction of wheat exacerbated the crisis R.B. Bennett’s new 1930 mandate hinged on his solution to the unemployment crisis which was looming over Western Canada and expectations were high. Unfortunately, the drought proved to be a serious liability for Bennett’s economic recovery plans. His pro-business, anti-interventionist inclinations provided little assurance to the millions of unemployed who were becoming increasingly desperate and agitating for change. According to Struthers, “the Tory leader was convinced that the present depression was a passing, mostly seasonal phenomenon”

R.B. Bennett’s new 1930 mandate hinged on his solution to the unemployment crisis which was looming over Western Canada and expectations were high. Unfortunately, the drought proved to be a serious liability for Bennett’s economic recovery plans. His pro-business, anti-interventionist inclinations provided little assurance to the millions of unemployed who were becoming increasingly desperate and agitating for change. According to Struthers, “the Tory leader was convinced that the present depression was a passing, mostly seasonal phenomenon” The capitalist philosophical crisis haunted Bennett. There was philosophical discord in Bennett’s party between Liberal capitalism and extensive government interventionism, so R.B. Bennett “who was [posturing] a radical change in government policy to ensure prosperity”

The capitalist philosophical crisis haunted Bennett. There was philosophical discord in Bennett’s party between Liberal capitalism and extensive government interventionism, so R.B. Bennett “who was [posturing] a radical change in government policy to ensure prosperity” After the collapse of Bennett’s unemployment relief efforts in the spring of 1932, he commissioned social worker Charlotte Whitton to write a two-hundred-page report on the Western crisis that was the growing liability on his government. As the director of the Canadian Council on Child Welfare, Whitton’s the most astonishing revelation was the argument that almost “40 percent of those then receiving relief in the West did not really need it…” adding that “…the plight of the people was pitiful but it was ‘not one deriving from the present emergency’ and therefore should not be supported by federal relief”

After the collapse of Bennett’s unemployment relief efforts in the spring of 1932, he commissioned social worker Charlotte Whitton to write a two-hundred-page report on the Western crisis that was the growing liability on his government. As the director of the Canadian Council on Child Welfare, Whitton’s the most astonishing revelation was the argument that almost “40 percent of those then receiving relief in the West did not really need it…” adding that “…the plight of the people was pitiful but it was ‘not one deriving from the present emergency’ and therefore should not be supported by federal relief” By late 1932, relief camps for single, unemployed males administered by the Department of National Defense were being established to extract transients from urban centres where political turmoil could ensue

By late 1932, relief camps for single, unemployed males administered by the Department of National Defense were being established to extract transients from urban centres where political turmoil could ensue The Conservative government’s strong-arm tactics using Bennett’s “iron heel of ruthlessness”

The Conservative government’s strong-arm tactics using Bennett’s “iron heel of ruthlessness” Out of desperation, R.B. Bennett turned to CBC public radio announcements in early 1935. Bennett’s New Deal echoed the interventionism of Roosevelt’s response to the Great Depression in 1933

Out of desperation, R.B. Bennett turned to CBC public radio announcements in early 1935. Bennett’s New Deal echoed the interventionism of Roosevelt’s response to the Great Depression in 1933 Unable to overcome the Depression, Bennett lost the 1935 election to his Liberal opponent, Mackenzie King. New leaders gained support by promising to help struggling constituents and to stand up to Ottawa. Electoral math problem SMD screwed him 18.7% drop in the support in 1935 election from 1930 47.5%(site) wikipedia). His larger failings were in the dealing of specifics in Great Depression, particularly federal-provincial relations with the four western provinces, the DND camps and the Regina Riot. The massive majority gained by King is more telling of the single member district electoral system than Bennett’s failures. King actually didn’t need the west to make a massive majority. Stevens Reconstruction party took 8.7% directly out of the Conservative party caucus** How much of the depression is truly Bennett’s fault is impossible to gage and historians seem to debate over the depth of his ineptitude rather than the successes he achieved. The 1935 election sealed Bennett’s fate as a failed leader, but this is only one side of a complex diverging understanding of Bennett and his accomplishments under the most dire of circumstances. While various writers describe to a degree the details of R.B. Bennett’s political strategy during the depression, they vary on the emphasis of his success or failure. Stevens and Tim Buck came back to haunt him electorally speaking.

Unable to overcome the Depression, Bennett lost the 1935 election to his Liberal opponent, Mackenzie King. New leaders gained support by promising to help struggling constituents and to stand up to Ottawa. Electoral math problem SMD screwed him 18.7% drop in the support in 1935 election from 1930 47.5%(site) wikipedia). His larger failings were in the dealing of specifics in Great Depression, particularly federal-provincial relations with the four western provinces, the DND camps and the Regina Riot. The massive majority gained by King is more telling of the single member district electoral system than Bennett’s failures. King actually didn’t need the west to make a massive majority. Stevens Reconstruction party took 8.7% directly out of the Conservative party caucus** How much of the depression is truly Bennett’s fault is impossible to gage and historians seem to debate over the depth of his ineptitude rather than the successes he achieved. The 1935 election sealed Bennett’s fate as a failed leader, but this is only one side of a complex diverging understanding of Bennett and his accomplishments under the most dire of circumstances. While various writers describe to a degree the details of R.B. Bennett’s political strategy during the depression, they vary on the emphasis of his success or failure. Stevens and Tim Buck came back to haunt him electorally speaking.