Chapter 48 – Old Lion, Young Mayor

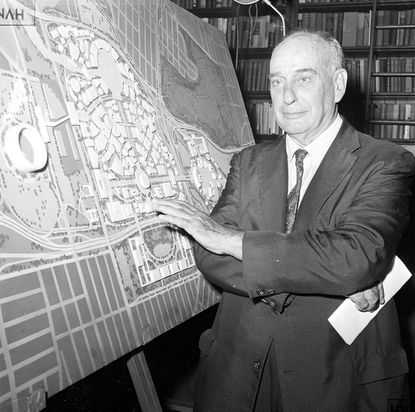

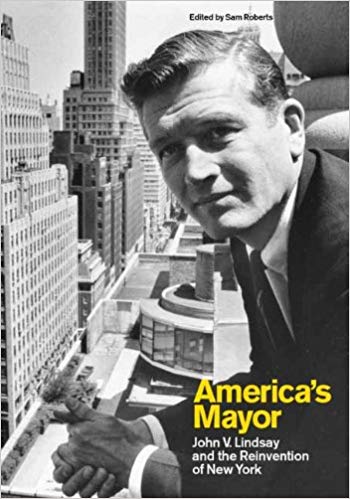

In 1966, John Lindsay was elected Mayor of New York. He appointed a Parks Commissioner who had been critical of Moses’s policies. Lindsay tried to remove Moses from all his posts, but he underestimated Moses who was too experienced and resisted.

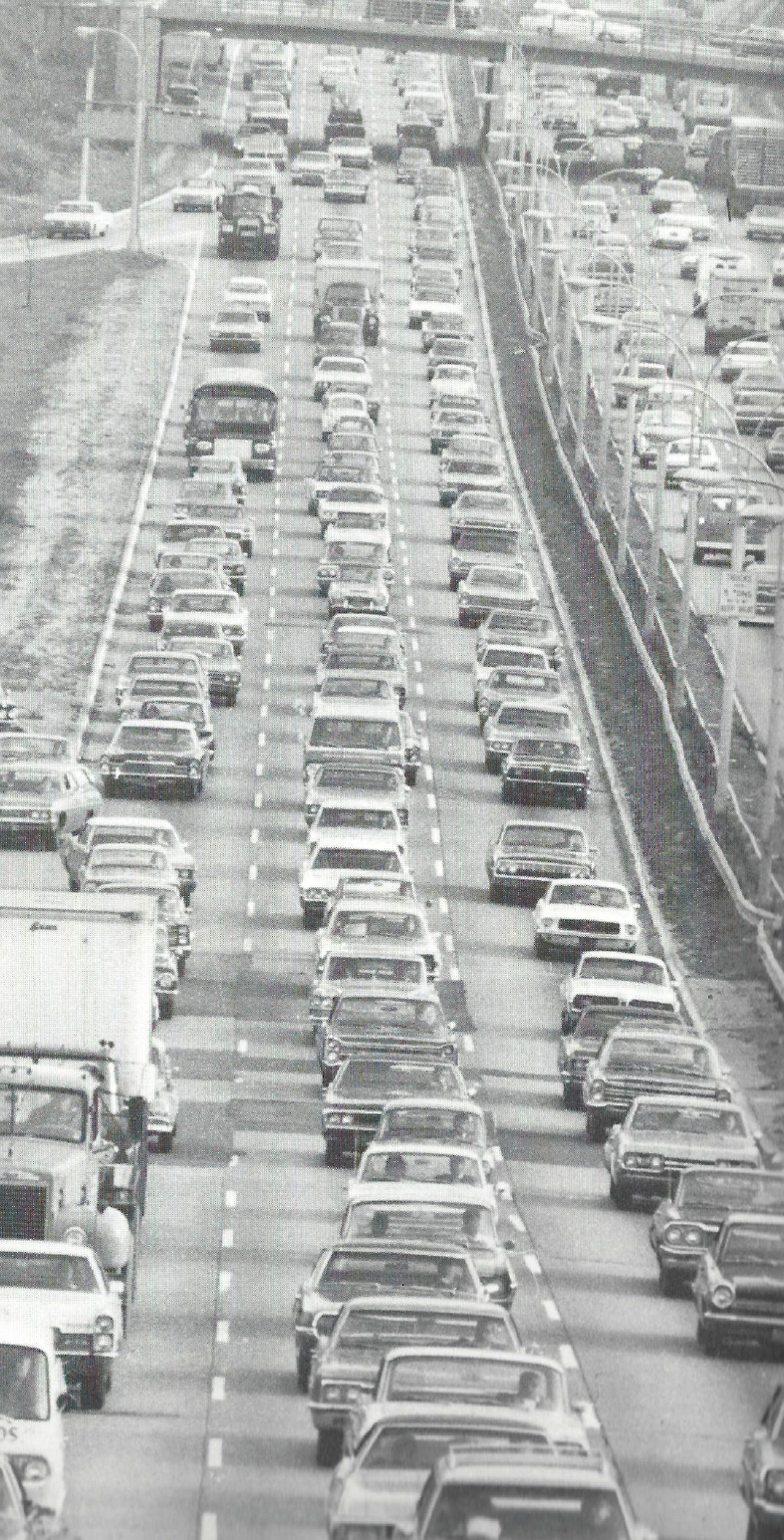

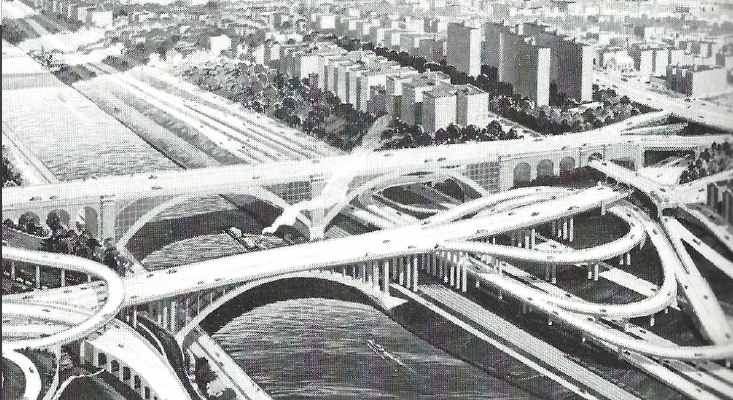

The Mayor also tried to force through some new mass transportation plans. He attempted to establish a new centralised transport authority. A memorandum of opposition was sent by Moses who pointed out that bond raising contracts could not be cancelled if bonds were still owing and the merger proposed by the Mayor would do this. Moses was offered the choice of resignation or firing. When the Mayor’s transportation chief met Moses to give him the choice, Moses was unperturbed.

The Mayor’s team remained confident that the Governor would support the transport proposal but by the time the proposal reached the legislature Moses’s team had done their work. When the public hearing was held at Albany, a City Hall executive was opposed by Moses, two former governors and a former mayor plus a host of representatives from cross-state power groups. The Mayor had been ambushed. When the press arrived, Lindsay and Moses met face to face, the former nervous, the latter relaxed. Lindsay left early, leaving his assistant to answer questions. For Moses, the line of the powerful proceeded to rubbish the bill. On the following day, Moses launched an attack on Lindsay, saying that he was sitting on millions of dollars’ worth of projects. By this time Lindsay’s bill was dead.

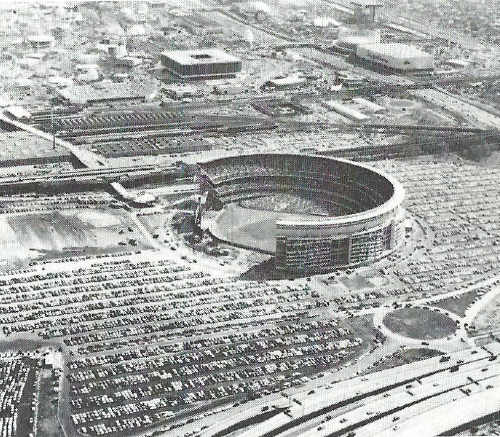

On July 11th Moses had arranged a ceremony to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the opening of the Triborough Bridge. There were crowds bussed in and glossy brochures. There was praise for Moses from the good and the great. But while Moses was still bidding his guests farewell, he received a letter dismissing him from responsibility for highways. He now had only one job left: The Chairman of the Triborough Authority, but he still was in control of Triborough money and he couldn’t be removed until 1970. But the Governor, his most dangerous enemy, was now moving against him.

Analysis & Key Takeaways

- Moving against Moses…