Chapter 27 – Changing

Power and Personality – Interplay.

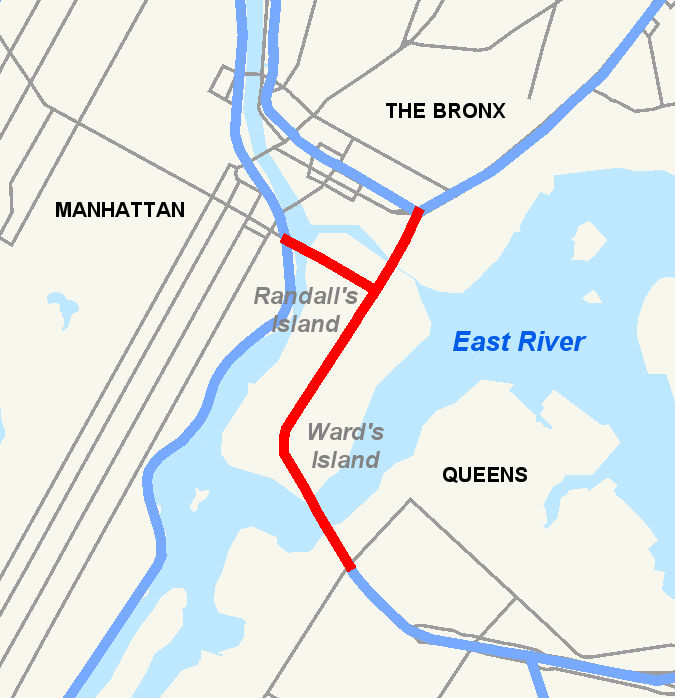

Moses now started to seek power for its own sake. In 1936, the New York City Tunnel Authority was established to build a Queens Mid-town tunnel. Moses asked to be a member but received no support from La Guardia and as a public official was ineligible. Moses persisted to get appointed but failed. He therefore resolved to destroy it.

The Mid-town tunnel experienced delays which threatened the necessary funding. Moses worked to delay it further by keeping the enabling bill stuck in committee. Most contemporaries thought that Moses tried to destroy the project purely because it was a challenge to his power. This revealed the lengths Moses would go to gain control.

As Federal housing funding became available, Moses hastily made up his own housing plans. The vast power involved attracted Moses. Moses circumvented the Mayor and presented his housing program directly to potential investors and the media, a program that conflicted with the Mayor’s own. However, a copy of the plan had fallen into La Guardia’s hands. As Moses was supposedly broadcasting his program to a large audience, La Guardia had cut him off the air. La Guardia also ensured that the Housing Committee rejected all Moses’s plans. Moses did not receive any of the housing projects.

La Guardia then moved to reduce Moses’s power in parks and transportation. The Mayor started to try to channel Moses’s energy into other areas of public works. However, Moses had always been skilled in taking a small institution and turning it into a source of great power. He was now to turn his mind to the institution known as the Public Authority.

Analysis & Key Takeaways

- Moses gained equal status with La Guardia through various means.