Chapter 28 – The Warp on the Loom

The Public Authority was a part private, part public authority and new in the United States, originally set up to collect tolls on rural roads. They mainly became established during the New Deal. Each had been established to fund one new development through the issue of bonds before turning them over to the city. The authority would thus be wound down.

The tolls collected for the new bridges was earning far more than was originally conceived. Normally this meant that the tolls would end faster than usual. However, Moses saw the extra revenues as a source of funds for further development, funds which would have little of the restrictions applying to federal funds. The increase in traffic over the bridges made them a much more attractive investment for the bankers and authorities could issue bonds to raise even more funds. There would need to be a change in the law to allow Moses to keep the surplus and to extend the life of the authority indefinitely. This change would give him the power and the money equivalent to running a sovereign state.

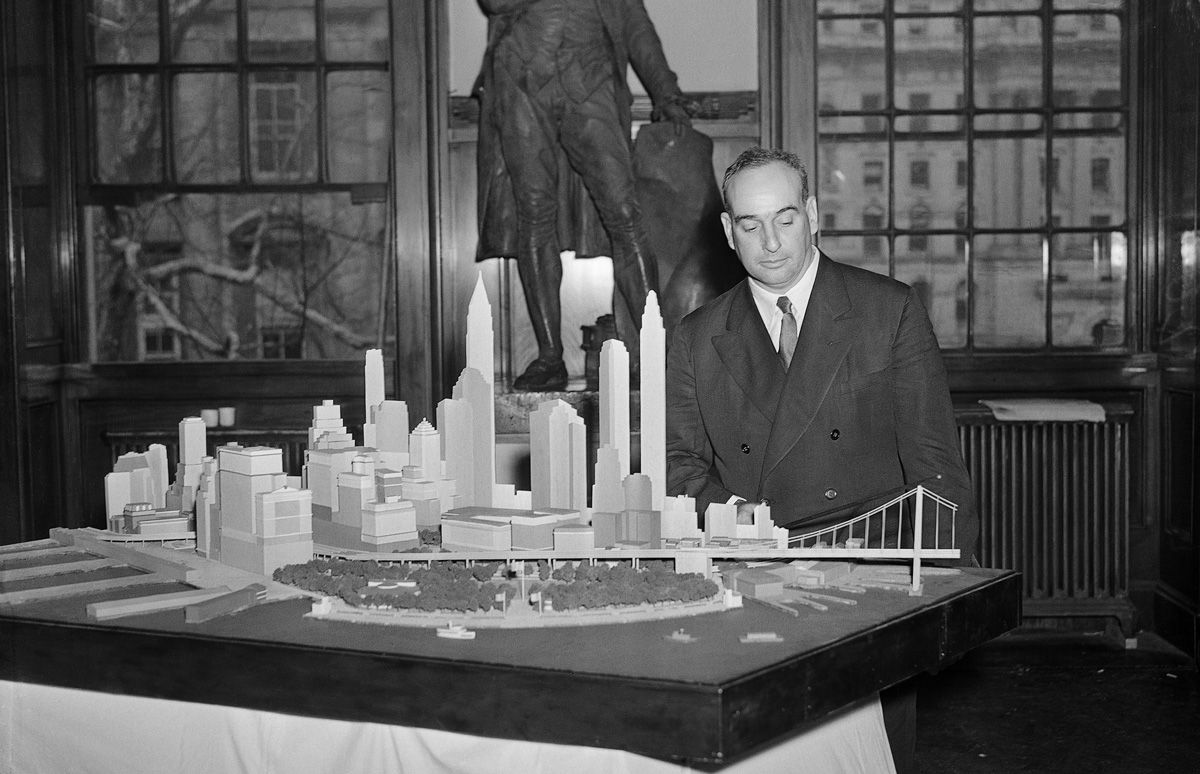

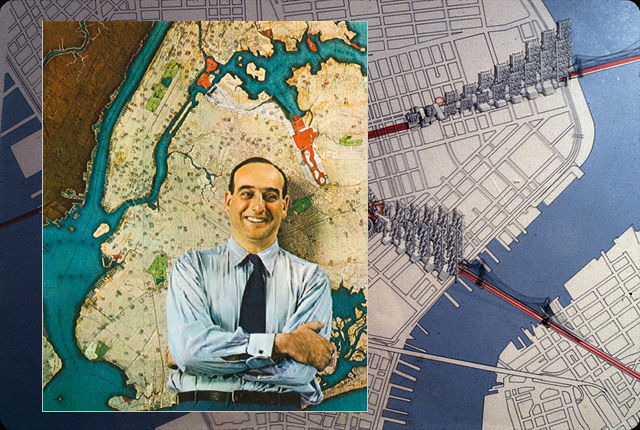

Moses drafted a new Triborough Act for the running of the Triborough Authority, allowing it to re-issue bonds indefinitely. As the authority could only be wound down once the bonds were paid off, the authority could exist indefinitely. The Act also expanded the role of the authority which would now encompass any connected development to the original development. This would allow the Triborough Authority to effectively develop parks, roads and bridges anywhere in the city. More than this, it could develop anything that connected with these developments such as housing. When the Act was passed, the Triborough Authority, and Moses as its Chairman, had as much power over city development as the City of New York.

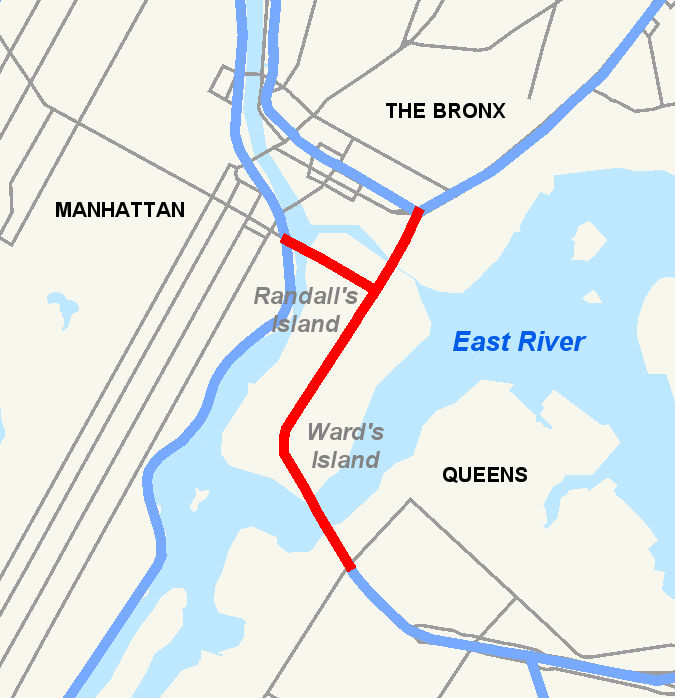

With the new power of the Authority, Moses has a major say in any development over the whole of the New York metropolitan area. Moses’s methods of persuasion would require secrecy and the Authority would give that secrecy. It would also give him the image of independence over red tape, the champion of the people over the dead hand of bureaucracy. This new institution would be the vehicle for the realisation of his dreams and the new head office would be on Randall’s Island, a moat protected kingdom outside of the jurisdiction of the city.

Moses no longer needed the protection of the Mayor and it was no longer politically possible for the Mayor to fire Moses. From then on, Moses no longer treated La Guardia as a superior, but as an equal.

Analysis & Key Takeaways

- Robert Moses’ largest defeat was pushing for the Brooklyn Battery Bridge: it was because of Mrs Roosevelt that his plan was thwarted apparently. Or it was just not a good plan and with hindsight, car dependency was a growing problem.